This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Dom Ruinart’s palette of Chardonnays

When it comes to sourcing top-notch, ageworthy Chardonnay in Champagne, most attention is devoted to the chalk-rich vineyards of the Côte des Blancs. But fruit from the Montagne de Reims has long played a vital role in the make-up of Ruinart’s flagship cuvée, Dom Ruinart. Richard Woodard reports.

Ask most people to name a top source of grand cru Chardonnay in Champagne, and certain names are bound to crop up again and again: Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, Avize, Chouilly, Cramant… the bleached chalk vineyards of the Côte des Blancs south of Epernay have long been the most prized places to grow the region’s white grape variety.

But head southeast out of the city of Reims and, within just a few kilometres, you’re surrounded by grand cru Chardonnay vines. This is Sillery, an unassuming, semi-suburban village close to the Vesle river and the TGV rail line. In the distance to the south, the view takes in the low rise of the Montagne de Reims and the windmill of Verzenay.

Sillery may not be a marquee name for Chardonnay, but it’s long played a vital role in the blend of Dom Ruinart, the house’s emblematic blanc de blancs cuvée. That’s partly because of history and geography, reckons Ruinart cellar master Frédéric Panaïotis.

“The Côte des Blancs has always accounted for the vast majority of the blend for Dom Ruinart,” he explains. “But, with Ruinart being located in Reims historically, the vineyards close to the city were included in the blend.”

Whatever the back-story behind its inclusion, there’s little doubt that Sillery fruit is in the Dom Ruinart blend today on merit, with the house both farming its own vines there and buying fruit from local growers. This is, after all, the only grand cru on the Montagne de Reims – indeed, outside the Côte des Blancs – that has more Chardonnay than Pinot Noir vines.

What’s special about Sillery? The most prized, east-facing vines are planted in a very different terroir to that of the Côte des Blancs, with up to a metre of topsoil before you hit the chalk – although there are a few pure chalk pockets too.

This terroir produces a riper style of Chardonnay, often with higher levels of alcohol and greater body and roundness – the perfect foil for the chiselled, linear precision of fruit sourced from the Côte des Blancs. “Montagne de Reims Chardonnay is more structured, less refined, but a bit more powerful,” says Panaïotis. “Playing with these two regions is, I think, a big asset for the house.”

Historically, Montagne de Reims Chardonnay – Sillery fruit, as well as that from neighbouring grand cru Puisieulx, and from Verzenay further south – has accounted for a surprisingly large slice of the Dom Ruinart blend: 28% in 2002, 25% in 2007 and 18% in 2009.

Latest release Dom Ruinart 2010, however – the first in modern times to be aged under cork, rather than crown cap – is dominated (90%) by Côte des Blancs fruit, with only 10% sourced from Sillery.

The reason for this is what Panaïotis calls “a very odd phenomenon” at harvest time. In 2010, a tropical storm in August had created problems with rot in Pinot Noir and Meunier, although the Chardonnay seemed to come through it unscathed. One September afternoon, the Sillery grapes looked ready to be picked – “they had those freckles you get on the grapes when they’re ripe”, recalls Panaïotis.

At 7am the next day, his phone rang. The Sillery grapes had turned brown overnight – a sure sign of botrytis beginning to infect the berries. “I’ve only seen that twice in my life,” says Panaïotis. “So, there’s very, very little Sillery fruit in Dom Ruinart 2010. Grapes like that have no potential of ageing, even if they are good.”

Fortunately, the quality of the fruit coming from further south was better than expected. “The Côte des Blancs Chardonnay in 2010 was surprisingly good,” says Panaïotis. “I did not expect the wines to perform so well. But, when I started to taste the base wines, I was blown away.”

The focus of Dom Ruinart is on the best vineyards – usually, but not automatically, grand cru – vintages that are exceptionally good for Chardonnay and, particularly, wines with the capacity to age. “For Dom Ruinart, one of the factors allowing us to select which wines is ageing potential,” explains Panaïotis. “But that’s not so easy to measure when you’re tasting the base wines.

“After some years, you start to get a feeling for that. It needs to be austere, but not in a bad way. It needs to have that shyness, but with complexity and depth behind it. It’s hard to describe. I think it requires a lot of experience and a lot of tasting. I have no interest in the wines now – I want to know what they can be.”

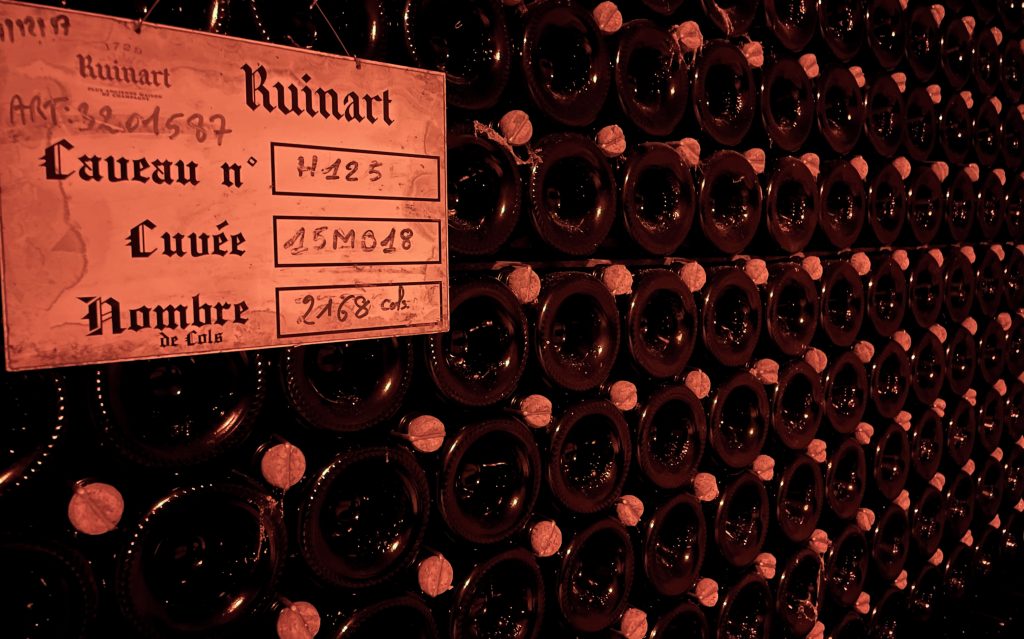

Ageing under cork has given Dom Ruinart 2010 a slightly more reductive character – the house’s research showed that, after six years, oxygen ingression with cork is less than with crown cap, and the company uses the “jetting” technique on the bottling line to minimise post-disgorgement oxidation.

But Panaïotis says many of those tasting the wine for the first time also detect a touch of wood. “That’s the cork,” he says. “Cork is oak, and it brings some of the same elements as oak, but not as much. The presence of bubbles enhances flavour, so you don’t need as much.”

He adds: “There are polyphenols in cork, and there are some tannins that in my opinion the cork is bringing to the wine. There’s extra structure and, for us with Chardonnay, it makes a difference. Maybe it wouldn’t be as much with, say, a blanc de noirs.”

Panaïotis admits that ageing under cork has brought complications, but is in no doubt about the wisdom of the move. “I knew that we would have to disgorge by hand, but I didn’t think about how much it would mean, how much it would cost. It created demands – but I think the results speak for themselves.”