This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

The Big Interview: David Jesudason

Author, journalist and the first BAME winner of Beer Writer of the Year, David Jesudason tells Jessica Mason how desi pubs can teach us so much about community and inclusion.

Walking back from primary school as a small child while having racist insults hurled at him was only a fraction of the trauma that David Jesudason has endured. The painful moments are crystalised in his memory and, as he sits in The Gladstone Arms pub in Borough, London, and sips his beer, he explains that being Asian in the predominantly white areas of Luton and Dunstable meant that he was often racially profiled. He says this led to him “learning” to soften his approach, knowing that he was always being appraised; something he admits upsets him to this day, despite knowing he is doing it.

“Primary school was hugely traumatic,” he says. “My mum was a nurse and she used to work nights, which meant that I was walking back from school aged six by myself, and kids were calling me names all the way home. It was like I was an alien to them. They couldn’t really understand someone being different to their whiteness. I went home and I told my mum, and she just said: ‘That didn’t happen,’ and that was it. After that, I realised that I really couldn’t tell her about racism.”

Later in life, Jesudason found that the people he considered his mates still used “racist terms” and laments: “I thought that I had to put up with racism to be friends with people, basically.”

After finishing his A-Levels, Jesudason chose Brunel University over an offer from Cambridge, which he says “in hindsight was a really good decision, because there were a lot of Asian people there and that was my first exposure to diversity across races”.

The first pubs where Jesudason felt at home were pubs where live music was played. The indie music scene was just getting going, and he fondly remembers The Bird in Hand in Dunstable, “a biker ’s pub” that he used to visit. “It was the age of Britpop and that music is always caught up in the idea of freedom for me,” he says, admitting that without that music, he found navigating pubs “very difficult”.

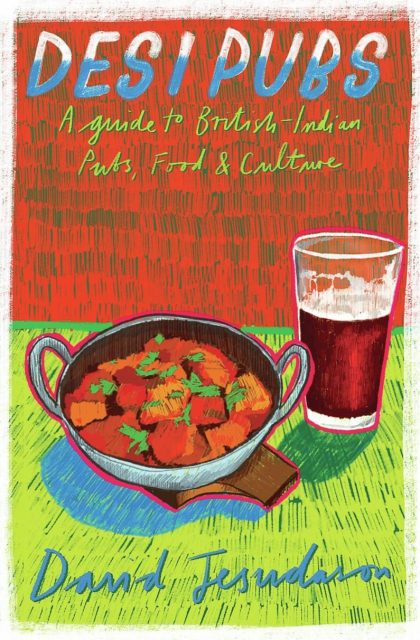

Jesudason highlights how racism and trauma often go hand-in-hand because racist attacks never stop weighing on someone once they have experienced them. The confusion and hurt over those experiences has had a knock-on effect. One of the most common ways in which Jesudason has experienced racism is through racial profiling in pubs. It’s one of the reasons why he wrote the book Desi Pubs; to show people that safe spaces exist within pubs and to reflect community values that, hopefully, everyone can appreciate and enjoy.

“I’ve always been obsessed with pubs,” he says. “It’s a love/hate relationship in some ways. Just this week I went to a pub and, when I walked in, the guy was so sceptical, to the point of being hostile. Then, after I’d had a few beers and a chat, he was the loveliest person in the world. But he profiled me as soon as I walked in, and this happens to me because they are sizing up who is going to be trouble.

“It just so happens that everyone has an unconscious bias and you’ll be more heavily profiled if you’re a person of colour.” As a result, he becomes “a softened version of myself; overly respectful. It takes more energy than I want to give on a daily basis to people. It makes you want to take singular action for the collective”.

Describing his book, Jesudason makes it clear that “it’s not about food or drink. It’s about Asians reclaiming spaces and making them anti-racist ones”. He explains: “The places that really flick the switch for me are those places where you might look at the exterior and go: ‘Oh my God, what kind of pub is this?’ And then you go inside and your subconscious prejudices are completely inverted, because it’s really diverse, and there are lots of different people there, and it has a real community feel to it.”

A common factor in desi pubs is, of course, the Asian food served to their clientele, but he reiterates how this is not the primary discovery people will uncover. “The food is great. But, for me, it’s not about the food, it never has been. I don’t review the food. Just the raw DNA. I’m more interested in social cohesion.”

The idea behind the desi pub was to change the default of “the white custodian” and, in doing so, Jesudason reveals that, after a while, people “realise that these aren’t brown spaces at all, they are spaces for everyone”.

The issue of inclusion within a pub setting is something Jesudason believes is taken for granted by many white patrons. “The thing is, white people don’t ever really feel like they are tourists,” he says. For these reasons, among others, he feels passionately about helping to shine a light on anti-racist spaces.

To amplify how well-knitted these pubs are within communities, Jesudason beckons over Gladstone Arms managing director Gaurav Khanna to talk through the Sikh meaning of sevadar. As Jesudason says: “For some pubs, the desis came in and made it a community space. Because many of them were previously train drivers, factory staff or would work in car parks, they worked really hard to save money to get the pub, and they really wanted to be a publican because it fits in with being a Sikh.”

The term sevadar, he explains, means selfless service and helping others, “and running pubs is one way of doing this”. In fact, sevadar fits the profile of “what we think a good landlord is”, Jesudason adds. Gaurav Khanna explains that a similar term ‘sewa’ is also “all about offering and giving”. Frequently, desi pubs in the Midlands will give away food to homeless people, which fits in with this understanding. Jesudason describes one desi pub in Bradford that has a church inside, and holds a Christian service every other week, despite the proprietor being Hindu. “They rent it out,” he says. “They also do things like curry and carols at Christmas. For them it is a community thing, and the community comes first.”

For The Gladstone Arms, community has also made good business sense. Speaking about the impact Jesudason’s writing has had on the pub and its popularity, Khanna admits that “the Desi Pubs book has definitely led to a big boost in business here. Different kinds of people are now visiting the pub. It has 100% had an impact on our clientele. Then, also because of the book, Time Out came in here too, which gave us a bit more visibility. The book has created more awareness around our pub – and all desi pubs. We like to converse here and talk to people about life experiences. That’s what being a public house is. More people are now coming in just for the chats. In this place, we celebrate each and every different type of person. We celebrate life.”

Speaking to Jesudason in a space where so many people feel warmly welcomed and accepted makes you feel like the UK has made some progress. However, as Jesudason says, it is not the case everywhere, unfortunately, and there is still work to be done to move things forwards so that the term ‘public house’ can go back to meaning just that: a place where everyone feels at home.

This shines a light on the fact that inclusivity and diversity are not the same thing. The pub industry needs to get better at reflecting diversity, but that alone is not the path to inclusion – and cannot in isolation help to encourage antiracist attitudes. Jesudason argues that “box-ticking and diversity for diversity’s sake is really damaging. Because what happens is, if you get employed in a job for not being who you are, but what you are, then you feel really insecure. Especially if you are only being employed because of the colour of your skin.”

Instead, he says, what the industry needs to do is ”read more books, or watch TV that has greater diversity”, because identifying as BAME doesn’t mean you’re “asking people to go and listen to African jazz or sitar music”. He picks out Star Trek as a good example. “It’s probably the most inclusive programme you could ever watch that has been created by a white person. I suppose someone might say: ‘I don’t like sci-fi’ but, fundamentally, it’s about how to get along with others.

After watching Deep Space Nine, Jesudason advises starting to think about how to engage the community, “because there’s no point in saying: ‘Ok, we’re going to employ a black person in our pub.’ You need to find a way of reaching more black people, or Asian people or women or gay people in order to get them to apply for the job.”

Why should pubs and drinks companies fight for that inclusion? “Because it means more markets and products. If you do it properly and truthfully, then more people might buy different beers, that’s why,” he says. Nothing will mend the racial trauma that Jesudason has experienced but, over time, as people become more educated about how to better celebrate our differences, the needle should start to move in the right direction. There are many ways that people from different cultures and backgrounds can help to broaden their perspective. And, if they do, there is more chance of the drinks industry moving forwards with an understanding of safety, inclusion and appreciation for all.

“My kids will have a much better life than I had,” says Jesudason. “Because a life marred by racism is a life marred by anger. It’s a big deal to find a pub that is accepting, and where you can celebrate being yourself.”