This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

The St Emilion Succession: Series 2

One might be forgiven for thinking that there are almost as many lawyers in St Emilion as there are vignerons these days. More accurate, I suspect, is that the lawyers of St Emilion are not exactly struggling for work. And one of the reasons for that is that old cases have a habit of generating new ones.

The most notable example, clearly worthy of its own Netflix series, is that of the classification itself – to which we will no doubt return when the latest in a long succession of legal processes reaches its anticipated conclusion later this week. But it is not the only one.

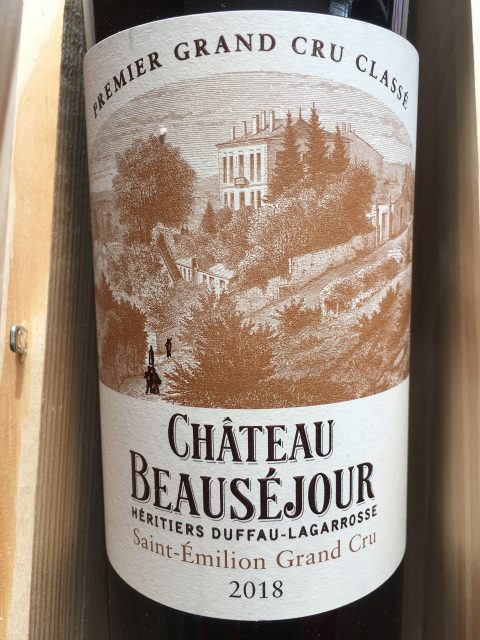

To the surprise of many, though in a manner anticipated in my last update on this multi-episode saga, the Cuvelier family has now launched a fresh legal procedure in the case of the contested acquisition of Chateau Beauséjour Héritiers Duffau-Lagarrosse.

To understand all of this, we first need a little refresher. As with all good sequels to a courtroom drama we need to start with just a bit of context.

‘Previously in the St Emilion Succession’: the story so far

Chateau Beauséjour Heritiers Duffau-Lagarrosse has been owned by the Duffau-Lagarrosse family since 1847. Its prestigious and highly regarded 6.5 hectares climb towards the limestone heights of the plateau of St Emilion and border those of Angélus, Beau-Séjour Bécot and Canon.

In November 2020 the chateau’s conseil d’administration (CA) sat to consider two competing bids for the future of the property. The first came from the Cuvelier family, of fellow Premier Grand Cru Classé B, Clos Fourtet. It would have seen the property continue to be managed by Nicolas Thienpont. The second came from Stéphanie de Boüard-Rivoal, of Premier Grand Cru Classé A, Chateau Angélus.

The CA’s votes were cast decisively in favour of the Cuvelier bid. It was reported at the time that the de Boüard-Rivoal bid has been rejected largely on the grounds that it would risk the subsequent incorporation of the vines of Beauséjour within the vineyard of Angélus itself – a claim strenuously denied at the time and subsequently by Stéphanie de Boüard-Rivoal herself.

But none of this seemed terribly important at the time, since the decision of the CA was taken as final and definitive.

But in the first of many plot twists, and to the surprise of practically everyone involved, the bid and the decision were referred to the local SAFER (La Société d’Aménagement Foncier et d’Établissement Rural) for further consideration.

SAFERs are, in effect, rural regulators of agricultural land transactions, acting under the authority of the French state, to ensure that all local and environmental factors are duly considered and protected. The immediate effect of passing the dossier to SAFER was to re-open the decision. For it gave, to anyone interested, 15 days to come up with a competing proposal (the period of time given to the original bidders to revise and re-present to SAFER their bids).

Unremarkably, given the extraordinarily short 15-day window of opportunity, it is extremely rare for new bids to appear at this stage in proceedings of this kind. But at the eleventh hour a third bid was submitted. In a second dramatic plot twist it came from none other than family member Joséphine Duffau-Lagarrosse and her co-bidders, the Courtin family (owners of the Clarins cosmetics group).

The three bids were first considered by SAFER’s technical panel, with the Boüard-Rivoal project the only one to receive an ‘avis favorable’. It now looked certain that SAFER would in effect overturn the CA’s decision in declaring it, and not the Cuvelier bid, the victor when it was due to make its announcement on the 25 of March 2021.

But nothing in this saga is as simple as that. As if to build dramatic tension (if any were needed), the decision was first delayed. It was then passed to a higher authority – SAFER’s own regional Conseil d’Administration.

On the 7 April 2021 the latter declared, again to the surprise and shock of practically everyone, that despite the original views of its technical panel, it was the Duffau-Lagarrosse/Courtin bid that should triumph.

The property was essentially entrusted to Joséphine Duffau-Lagarrosse who has presided over it ever since; the matter was seemingly closed.

The justification offered by SAFER for the decision is itself interesting. The Duffau Lagarrosse-Courtin bid, they suggested, was preferred because it would not threaten to divide the property (an implicit suggestion, of course, denied by Stéphanie Boüard-Rivoal), would maintain the historic link between the property and the Duffau-Lagarrosse family, would support sustainable viniculture and biodiversity in the vineyard (probably true of all three bids) and would install a young winemaker at the property (something also true of the Cuvelier bid).

Series 2

Not for the first time a natural conclusion of this drama seemed to have been reached. But once again the script writers had other ideas. And their plot had been very well-devised. For way back in series 1, immediately after SAFER’s technical panel had judged in favour of the de Boüard-Rivoal bid, Philippe Cuvelier had said the following to Terre de Vins:

“It needs to be remembered that 92% of the current shareholders of the property were in favor of a sale [of the property] to the Cuvelier family. Given this, what right do SAFER and its technical panel have to interfere in this matter? If the final decision is not favorable to us, we are ready to do everything possible to shed further light on this episode” (my translation).

The intention was clear. And if this reads now like an implicit threat, it should come as no great surprise that in the last few days it has been acted upon. Nearly six month on, on the eve of the limit for the contestation of SAFER’s decision, the Cuveliers have launched their own legal process. Represented by their Bordeaux solicitors, they are suing SAFER, the former ‘heritiers’ of the property, the new operating company (SAS Beauséjour-Courtin) and, in her own name, Joséphine Duffau-Lagarrosse (the new general management of the estate).

This might all seem rather personal. But, as Mathieu Cuvelier explained again to Terre de Vins.

“We go into this process in a serene and peaceful manner, it is above all SAFER that has offended us. We are not digging the dirt and we are not seeking to pick a quarrel between neighbours. We have nothing at all personal against either the Courtin family nor Joséphine Duffau-Lagarrosse. We will perhaps gain nothing personally. But we hope to contribute to the improvement in the practices of this archaic institution (SAFER)” (my translation).

We tend to think of St Emilion politics as rather febrile, visceral and personal – and we may well be right to do so. But in this case – and in public, at least – the leading protagonists have all conducted themselves in an impressively diplomatic manner, couching their disagreements in terms of principals rather than personalities.

A first hearing with take place on 6 December in Libourne to determine whether there is a legal case to answer and whether proceedings can commence. All of Bordeaux will be watching and listening – and we will be there to follow the next instalment of this St Emilion soap opera.