What’s next for Japan’s Unesco-recognised drinks industry?

From centuries-old traditions to innovative fine dining, sake-making with koji mould goes from strength to strength, one year after it joined the Unesco list of intangible cultural heritage.

‘Traditional knowledge and skills of sake-making with koji mold in Japan’ officially joined the list of Unesco intangible cultural heritage on 5 December 2024. Thus, while 2025 was another year in a tradition that stretches back centuries, it was a particularly significant one for Japan’s drinks industry.

In Japanese, sake can mean any alcoholic beverage, and so the designation includes the fermented rice-based product (simply known as sake on most international markets, and referred to as Japanese sake here). It also includes the rice-based products mirin and awamori, as well as shochu (which can be made with rice, sweet potato or barley).

Thus, when a first-anniversary event was held in Asakusa, Tokyo on 6 December, it welcomed a broad range of stakeholders to celebrate: sake brewers, educators, mixologists and more.

Yet it was not just a celebration: the year since sake-making with koji mould’s Unesco inscription offers a fitting opportunity to reflect on the generations-old industry’s position in the 21st century.

A distinctive culture of cultures

The Unesco recognition has not changed sake production. That has been a near constant for more than 500 years in Japan, giving the country its national drink. Inclusion on the list has, however, emphasised that Japan’s practice of sake-making with koji mould is unique in the world.

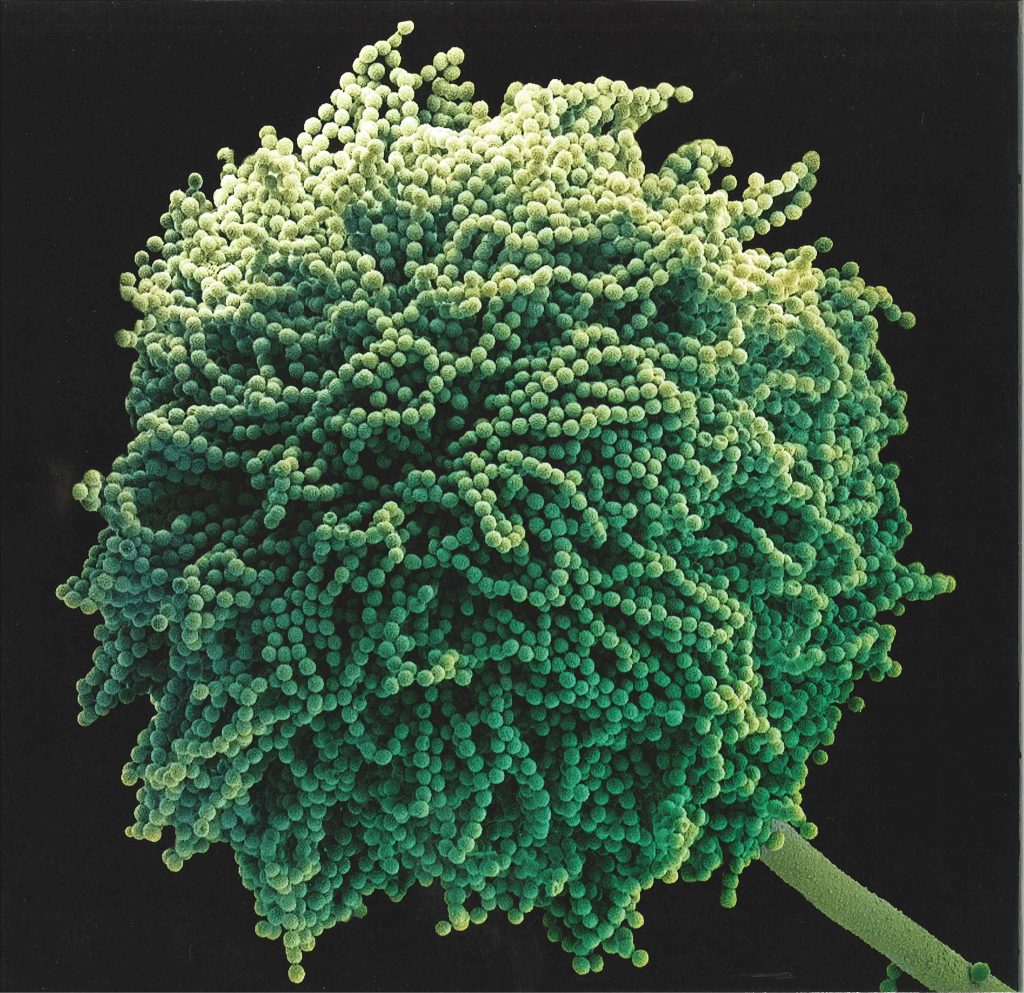

Using microorganisms to make food and drink is a widespread practice around the world, but the technology and culture of growing koji mould on steamed ingredients is particularly Japanese.

It relies, firstly, on the mould itself. While there are more than 97,000 species of mould around the world, a gradual process of selection and refinement has resulted in three being primarily used in sake-making.

Aspergillus oryzae (yellow koji mould) is mainly used for the production of Japanese sake; it grows on steamed rice to produce rice koji (koji mould cultivated on steamed rice), which can then be fermented.

Shochu and awamori production, meanwhile, cultivate Aspergillus luchuensis (black koji mould) or Aspergillus kawachii (white koji mould) on steamed raw materials such as rice and barley, each selection made according to the desired style and the needs of the producer.

Even within these species, there is variation, with specific strains creating different types and amounts of enzymes or forming different acids. The choice of strain may be due to many factors: the producer’s ’s climate, the local raw materials or the eventual intended style, for instance.

An important industry therefore emerged in the 18th century: specialised producers of tane-koji, or koji starter. From these spores of koji mould, brewers are able to create the wealth of koji-based beverages for which Japan is now famous.

Banding together

The emergence of the tane-koji industry confirms another important facet of sake-making with koji mould: it has built up a unique industry and culture. Indeed, much like koji mould itself, the overall impact is thanks to a culture of individuals working together.

In inscribing the knowledge and skills of sake-making with koji mould, Unesco has recognised the inheritance of the sake industry. Although technological advancements have played their part in advancing sake-making, this is still largely an industry defined by the knowledge, techniques and customs passed down by the likes of toji (master brewers) and kurabito (brewery workers).

“It cannot simply be preserved as paper documents or video footage. It is, above all, ‘people’ who pass on that tradition,” explains Tatsuya Ishikawa, chairman of the Japan Toji Guild Association.

“Therefore, it becomes important to create an environment in which people who are motivated to engage in sake-making can enter this path and acquire traditional techniques.”

In order to foster that environment, industry bodies continued in 2025 to fan the flames of demand for Japan’s national drink. The Preservation Society of Japanese Koji-based Sake Making Craftsmanship in Japan and the Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association (JSS) worked on large scale events in 2025, for instance promoting sake through the Osaka-Kansai Expo and the Kokushu Fair, a celebration of sake and shochu.

The JSS has furthermore continued its partnership with the Association de la Sommellerie Internationale (ASI), introducing sake to its competitions, seminars and events.

It is bringing Japan’s products to the world’s attention. Reese Choi, who won the top title at the ASI Asia & Pacific Best Sommelier Contest held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in September 2025, comments: “Sake is not merely a drink; it is Japanese culture itself.”

Growing internationally

Japanese sake’s upward trajectory on international markets was plain to see in 2025: from January to October, exports grew 8% year-on-year. That built on success in 2024, when exports reached a record 80 countries and amounted to a value of ¥43.5 billion.

Moreover, Japanese sake is finding audiences outside its mature markets, with the JSS promoting it to regions such as Eastern Europe and Latin America.

In such markets, extra effort is paying dividends. Dawid Sojka, a sommelier and educator in Poland, is making the case by providing tastings with up to 20 different sakes before customers then make a purchase.

“About 90% of participants leave having found ‘their favorite sake.’ In immature markets, this successful experience is what truly matters,” he comments.

In mature markets, meanwhile, sake is positioning itself at the cutting edge of high-end dining. That is certainly evident in wine lists. Of France’s 31 three-Michelin-starred restaurants, around 20% now include sake on their drinks list.

More impressively, koji is finding its way into the kitchen, as chefs experiment with the mould in their cooking.

Andoni Luis Aduriz, the much-garlanded chef behind Mugaritz in Spain’s Basque region, uses it to craft unusual tastes. “What most attracted us to koji was its capacity for transformation,” he explains, “a mould that produces enzymes (amylases and proteases) capable of converting starches into sugars and proteins into amino acids; expressed in the language of taste, this means sweetness and umami, texture and succulence.”

He believes that the dishes made with koji “speak of delicacy and subtlety” while also allowing a perfect pairing for the Japanese sake on the menu.

“Japan has been, and is, an inexhaustible source of inspiration,”he concludes. “Working with koji and sake at Mugaritz, we always feel a little bit more a part of Japan.”

At Jöro in Sheffield, England, the mould’s potential is similarly viewed as exciting. “Koji now plays a vital role in our cooking,” says co-owner and executive chef Luke French. “The most appealing aspects are the flavour profiles and aromas it produces through different types of koji and different preparations of using it.”

Sake made with koji mould may now be an officially registered heritage practice, but it is reassuring to see it is still inspiring new and innovative creations. Unesco is helping preserve sake-making’s traditions; the world is ensuring it stays relevant in the 21st century.

Related news

Imported beer could 'disappear' from Russian retail

Double Dutch: ‘Taiwan’s tonic comeback is the perfect moment to reimagine the G&T’