Top 10 ways Champagne is tackling climate change

Champagne’s climate has been transformed over the past few decades, but how should the industry react to the changes? Patrick Schmitt MW lists the top 10 developments taking place right now.

IT MAY have been a passing comparison, but it was a striking analogy for the handful of press gathered at Moët Hennessy’s UK headquarters in July this year.

According to Ruinart chef de cave Frédéric Panaïotis – who was presenting his maison’s first new cuvée in 20 years – the climate of Champagne today is similar to that of Châteauneuf-du-Pape in the 1980s: an area of southern France hot enough to ripen Grenache to a glorious and heady peak.

But what was the basis for such a conclusion? And what does it mean for the character of Champagne being made today? Those questions he went on to answer fairly comprehensively, but the tasting got me thinking: how is Champagne changing its production techniques to ensure that this benchmark sparkling wine retains its appeal, which is based around a wonderful balance between freshness and flavour richness – as well as, you could add, age-worthiness.

In other words, should Champagne continue to get hotter, and drier, can the region still produce palate-cleansing fine fizz for immediate consumption, as well as cellaring?

Well, it seems the changes already occurring in Champagne are being done very much with this in mind, as well as securing the supply of the product in the face of not just a warming climate, but a more erratic one.

As a result, I’ve drawn up what I think are the 10 major developments in Champagne to weather climate change – at least in the near future. But, before exploring those, just what has been happening climatically in Champagne in its recent history, and how has it affected the product?

Huglin Index

For Panaïotis, one of the best measures of change comes with the Huglin Index, which is essentially a measure of growing degree days that is used to classify viticultural regions from “very cold”, such as Québec, to “warm”, like Jerez. Using Champagne’s hottest vintage on record, 2018, he said that the region reached a Huglin Index total of 2,200, prompting him to state that conditions in that year “were more like Châteauneufdu-Pape in the ’80s than Champagne” – or indeed, like the Port-producing region of the Douro today.

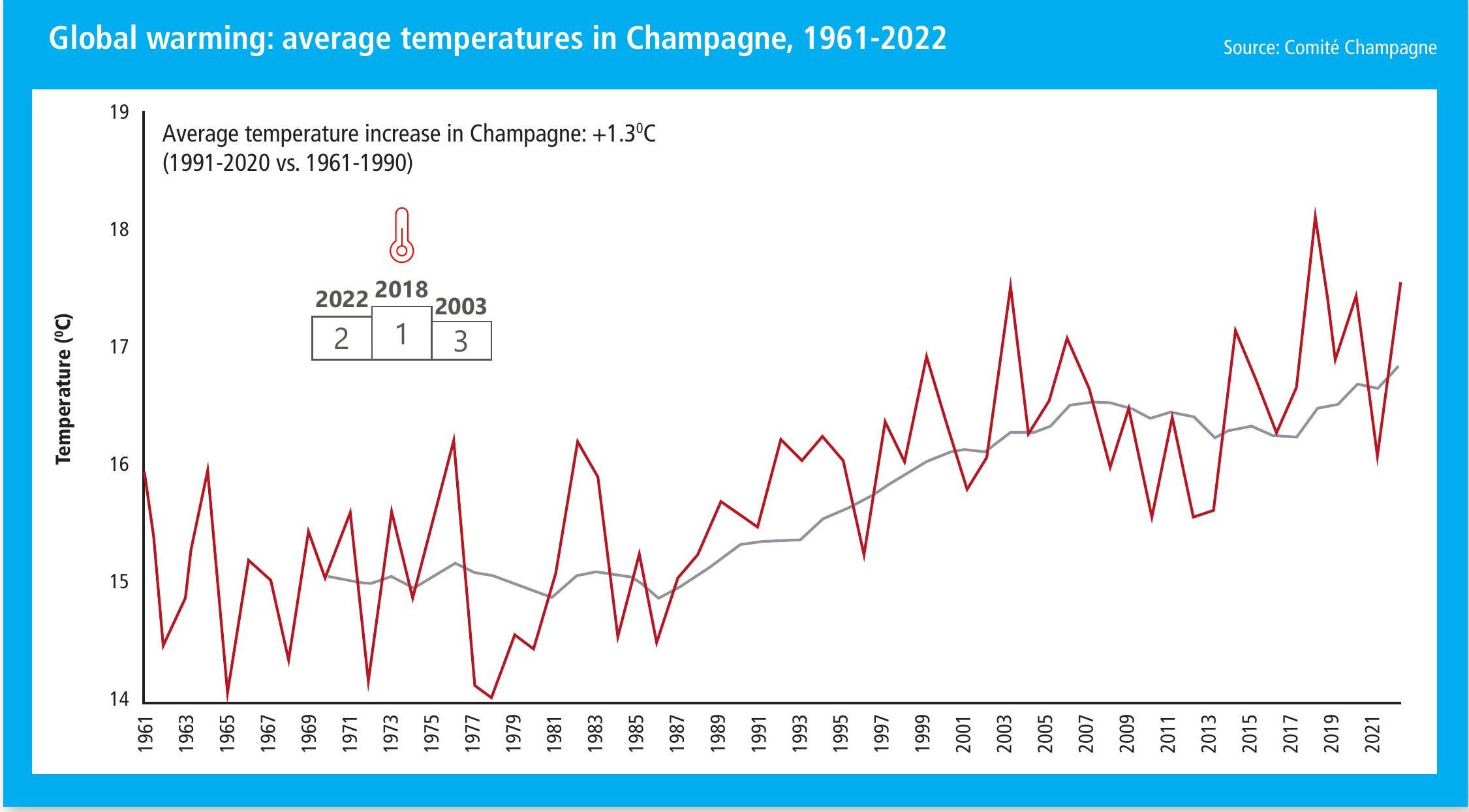

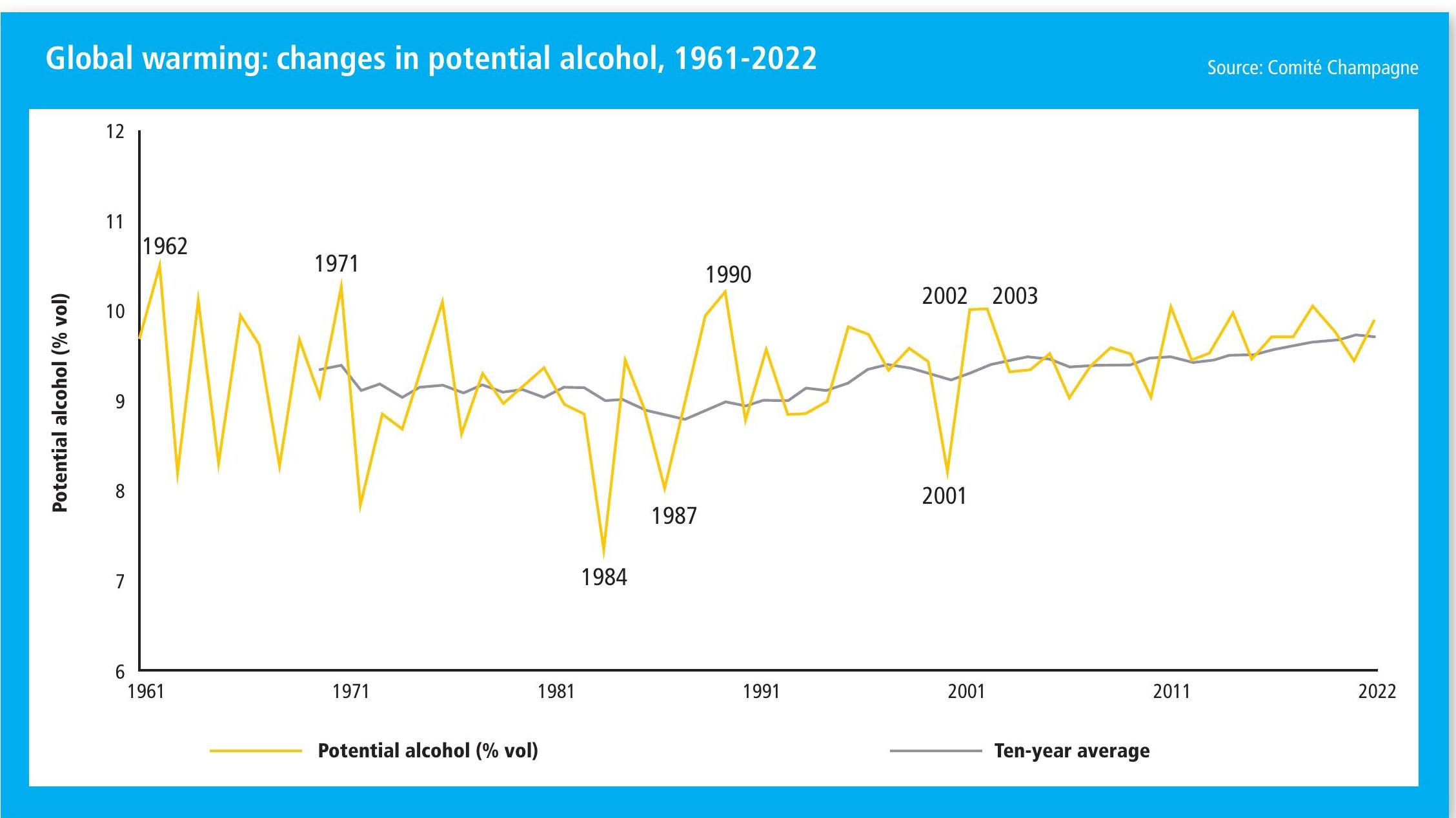

Looking back over time, Panaïotis showed how Champagne had shifted from a “cool climate to a temperate one”, since the 1960s, although in certain vintages, such as 2003, 2018, 2020 and 2022, it would be classified as a “warm” region, like Montpellier, he said.

Speaking of more recent climatic changes in Champagne, he said that the past century’s warmest years, such as 1964 and 1976, “are the norm of today”, adding that the three hottest vintages (2018, 2022 and 2003), “did not exist in the past”.

“Some might compare 2018 with ’59 or ’47, but this is not the case; it is not the same – we have entered a new era,” he said, referring to the hottest vintage in Champagne compared to legendary warm years of the past century.

While the message sounded alarmist, Panaïotis said that a warming climate in Champagne had so far been good for the region. Again, looking back, he said that years such as 1965, 1972 and 1977 were terrible, adding: “We could barely make wine,” before noting: “Those years don’t exist any more, which is good; we don’t have to deal any more with completely unripe grapes.”

Indeed, he showed how the average temperature in Champagne had gone up by 1.3o C, comparing the period from 1991-2020 with 1961-1990, remarking: “It is not actually that much, and it helps to ripen the grapes.”

Panaïotis also had “good news about rainfall”, which he said “has been stable since the ’60s”, when considering average annual totals, adding: “So we don’t yet suffer in our region from water shortages, even if we see more rain in winter and drier periods, even droughts, in summer.”

However, an area of change that is less positive for Champagne concerns a shortening of the growing season, mainly due to warmer, sunnier and drier summers accelerating the grape-ripening process, but also due to an earlier start to the season. This, Panaïotis stressed, was not due to an earlier bud-break, but an earlier flowering of the vines.

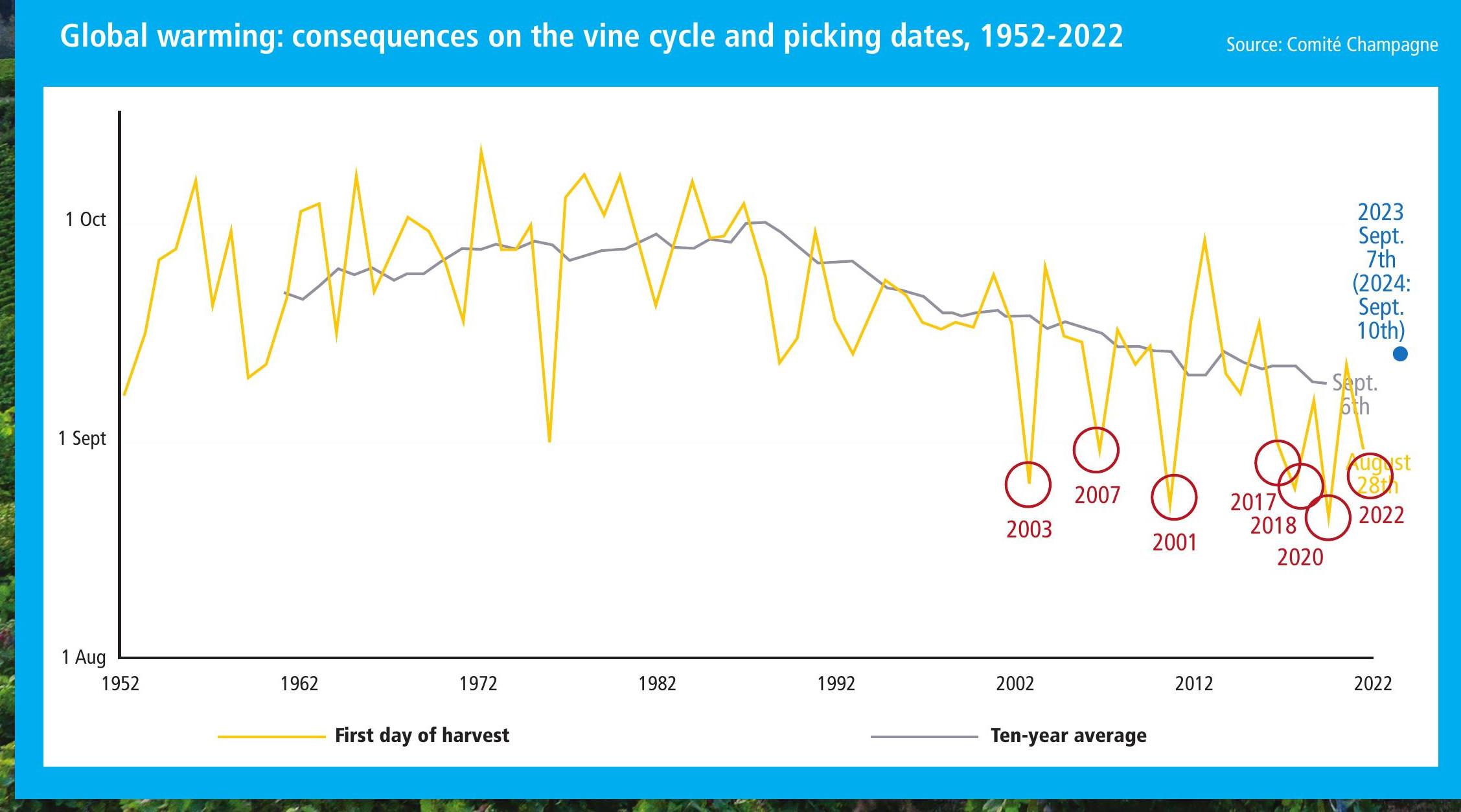

“An early flowering combined with warmer summers ended up with our first harvest in August, which was in 2003,” he said. “We’ve now had seven harvests in August [2003, 2007, 2011, 2017, 2018, 2020 and 2022],” which means that picking the grapes in this month was becoming “the norm” in Champagne, when late September was a common start date in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. In more recent history, 2013 was an exception, as it was a late harvest, which he said “was mainly due to a late flowering”.

Panaïotis then pointed out that the number of days between flowering and harvest “used to be 98-99 days, but now it is 87 days”. In 2003 and 2019, it was 80 and 81 days respectively, meaning that “the cycle is considerably shorter”.

He added: “Eighty days is too short to have fully ripe grapes, taking into account physiological maturity.” More generally, he said that a shorter cycle means “losing potential complexity”.

As for frost risk in Champagne, Panaïotis said that the region did not appear to have become more prone to damage from freezing conditions at the earliest stages of the growing season.

“We can’t say that milder winters translate into an earlier bud break – so far it’s not the case,” he stated. While the region is still prone to spring frost damage – with Champagne, for example, “seeing 3% of the area damaged by frost this year – it’s not like we are seeing bud break in mid-March”, Panaïotis added.

Nevertheless, as noted above, “If we look at the flowering period, it is a clear indication that springs have been warmer – from the late ’80s we have lost about two weeks: we are now flowering two weeks earlier than what we used to,” he stated. Finally, speaking about the current conditions in Champagne, which have been unusually wet in 2024, he said: “It is a good year for trees and hedges, but a bit more challenging for vineyards and grapes.”

As db has covered extensively online during the past few months, 2024 has so far been an exceptionally rainy growing season, with the Comité Champagne noting that the “entire vineyard” has “suffered from strong but controlled mildew pressure”.

Indeed, drawing attention to the contrasting conditions in Champagne year-on-year, Michel Drappier told me in mid-September that, while 2023 in Champagne “was like Morocco, this year, it is like the west coast of Ireland”.

He added: “If global warming means that Champagne will have a future climate like this one, then we have a real problem.” So much for the problems facing the region. What are the potential solutions?

1. Improve vineyard soils

With a warming climate come extremes, be it the switch from drought to flooding, or from frost to heatwave, and the best manner to deal with such a threat is to improve the resistance of vines to variable weather. Some of these measures can be embarked upon now for quick results; others may take decades.

One with immediate benefits is managing soils to improve the carbon content and microbiological life.

“We have to prepare for the future,” says Moët & Chandon cellar master Benoît Gouez, before identifying a change in the former, which sees Moët adopt regenerative viticultural practices across its estate.

“It means not having a monoculture any more: now we have grass and vegetation in the vineyard, which protects the soils and provides auto-nutrition,” he says, adding: “This is something you can implement quite fast.”

Indeed, 100 hectares are currently managed this way. Aside from sequestering carbon from the atmosphere and storing it in the soil, the plant cover keeps soils cooler during the summer – and therefore the vines too – as well as wetter during dry periods. But if there’s intense rainfall, it helps the water seep into the ground, reducing the chance of flooding, while preventing soil erosion.

Of course, Moët is not alone in taking this step, with all the major players trialling a similar approach – which sees minimal tilling of vineyard soils – while Maison Perrier-Jouët is aiming to go 100% regenerative across its vineyard estate by 2030, according to cellar master Séverine Frerson.

Meanwhile, Champagne Louis Roederer, which manages its 240ha estate organically, is seeing a benefit in freshness. According to cellar master, Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, the practices produce wines with a lower pH and more dry extract, which he attributes to the fact that the vines root more deeply, and yield 20% less than those in conventional farming systems.

2. Reduce planting density

Less immediate, but no less significant in terms of adapting vineyard management to a changing climate, is a gradual shift towards lower-density plantings in Champagne. Called ‘vignes semi-larges’, the recently-approved initiative sees permitted vine row spacing increase from a previous maximum of 1.5m to 2.2m, with many benefits observed from the change. One is easier mechanisation, another is better resistance to dry spells, while a further plus is a lower susceptibility to spring frost, as well as an improvement in air circulation, which can reduce fungal disease infection.

Gouez says: “We are transforming the way our vineyards are planted, from high-density to ‘semi-larges’ vineyards, which we have done on 50ha, and it has shown benefits in terms of carbon footprint and better protection of the vines.” Indeed, this wider spacing allows vines to produce more foliage, which contributes to a lowering of the sugar content and an increase in the acidity levels in the grapes.

Partner Content

However, as Gouez himself admits, this will be a gradual change that will only come with the replanting of vineyards. Notably, the removal of old vines is, however, a further change that some in the region believe needs to be made. While established, older vines tend to produce lower yields of more intenselyflavoured berries, they also have lower levels of acidity.

Odilon de Varine, head winemaker at Champagne Gosset, comments: “The vineyards in Champagne are too old on average, resulting in less malic acid in the musts.” He advocates replanting with younger stock, arguing: “So, the first action to be taken should be the renewal of vines… Younger vines would lead to a higher level of acidity and less accumulated sugar.”

3. Plant ‘forgotten’ grapes

If the region is to start removing its older vine stock, what should it replant with? For a start, growers should consider rootstocks that are better adapted to handle long periods without rainfall because, although average annual precipitation has changed little in Champagne, it tends to fall in more intense bursts, with greater gaps between episodes. As a result, François Moutard, cellar master at Champagne Moutard, says that he is changing the rootstocks as he replants at his estate, “adding some more resistance to water stress with 41B or Fercal rootstock”.”

But the main development when it comes to increasing vine resilience for forecast warming and drying in the region concerns grape varieties – with some looking back, others trialling the new, and a few doing both – when it comes to finding a grape-based solution to retaining freshness and quality in Champagne.

Those with an eye to the past include Bollinger, which has over the last decade been replanting the ‘forgotten’ grapes of Champagne in a bid to combat the effects of summertime heatwaves. While the region today is almost entirely covered with Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Meunier, split roughly into equal parts, historically seven varieties were in regular use, with the other four comprising Pinot Gris (called Fromenteau in Champagne), Pinot Blanc (known as Blanc Vrai in the region), Arbane and Petit Meslier. And it is the latter two that hold particular interest for Bollinger because of their high levels of natural acidity.

Bollinger cellar master Denis Bunner explains: “In 2018, which was a very early year, with our harvest starting on 23 August giving very mature grapes, we found that the two old varieties, Petit Meslier and Arbane, had a pH below 3.0, because they ripen more slowly.” While Bollinger is working with the historic grapes of Champagne on a trial basis, there are other producers who are already making and selling bottles using the old varieties of the region.

Notable among these is Champagne Château de Bligny, which makes the Cuvée 6 Cépages, combining the three classic varieties with Arbane, Fromenteau and Petit Meslier, and Champagne Drappier, which produces the Quattuor Blanc de Quatre Blancs, comprising equal parts Chardonnay, Arbane, Petit Meslier and Pinot Blanc (see box, page 78).

The latter producer has also released its first Champagne made using Fromenteau. Meanwhile, Champagne Moutard makes a varietal Arbane, based on a vineyard planted by François Moutard’s father Lucien in 1952 – a man “who had great foresight”, says François, who also notes that this particular grape is “seeing a resurrection” because “it resists heat very well”.

4. Select for resistance

The region’s largest Champagne producer, Moët & Chandon, is also looking to the past, but incorporating the big three grapes too. Last year, the maison inaugurated a vine collection called Essentia, which comprises as many as 1,800 different grapes. Called a living library, the experimental plantation is made up of cuttings from vines planted before 1970, either from within Moët’s own vineyards, or from its suppliers, with each plant chosen for its special characteristics. “It could be remarkable because of the shape of the grape, the timing of maturation, or its resistance to drought,” records Gouez.

Having started this process in 2019, Moët now has 600 different Pinot Noir vines, 600 of Meunier, 600 of Chardonnay, and 300 ‘others’, which include the aforementioned ‘forgotten varieties’, as well as further grapes, such as a colour mutation of Chardonnay that has pink skins. “There is a lot of genetic variation within each grape variety, and the idea is to identify and preserve the genetic diversity of our classic varieties,” says Gouez. The next step is selecting from this nursery the best raw material for changing conditions – whether it be the vine’s heat, drought or mildew resistance – and planting those vines for Champagne making.

5. Trial hybrid grapes

While Gouez believes that there are “solutions for the future with our current varieties”, Moët is also trialling hybrid grapes, such as Voltis, a new vine variety that is more disease-resistant and requires less use of protective products.

However, claiming to be the first producer in Champagne to grow all eight grapes authorised for use in the appellation was Champagne Drappier in May 2023, when head of the house Michel Drappier said he was planting Voltis alongside the full suite of seven non-hybrid varieties that were already planted at his property in the Côte des Bars.

Voltis is a white grape, and has been created by France’s INRA and Germany’s Julius Kühn as part of a special project launched in 2000 to develop PIWI varieties. The new variety contains genes from Vitis berlandieri, Vitis rupestris, Vitis vinifera and Muscadinia, and has been bred to resist both powdery and downy mildew. Its benefits are particularly apt after a vintage like 2024, in which a wet summer created immense disease pressure for growers.

The inclusion of Voltis within the Champagne region’s rules – known as the cahier des charges – means that it is the first PIWI grape to be included in an AOC specification. Voltis is only authorised on an experimental basis, with plantings limited to less than 5% of a property. Also, any wine made from Voltis can only be used up to a maximum of 10% of a blend. Such rules will be in place over the next 10 years, during which time the quality of Champagne produced from the grape will be analysed – and, should Voltis not yield a fizz of sufficient quality, after this trial period it could be removed from Champagne’s cahier des charges.

6. Alter site selection

Finally on the viticultural side, winemakers are working with Champagne’s existing grapes to craft crisp-tasting fizz. As Charles Duval-Leroy from his family’s Champagne house rightly points out, the timing of harvest can be “adjusted” to ensure grapes are “picked at optimal ripeness levels”, while “preserving acidity”. Another measure that’s available, to the négociant at least, is altering where the grapes are sourced from.

Florent Roques-Boizel, CEO at Champagne Boizel, explains: “We have in recent years adapted our approach to preserve the style of our cuvées… in our cru selection we favour some cooler (north-facing, often) villages: a good example is Grauves in the Côte des Blancs, where we have increased our presence recently.” He adds: “We have also increased the share of Chardonnay and Meunier in our blends, decreasing slightly the Pinot Noir, and also increased the percentage of reserve wines.”

Others are lucky in their locations. For example, Rémi Vervier, CEO and oenologist at Champagne Palmer, records: “More than 50% of Champagne Palmer ’s great terroirs are located on the Montagne de Reims (north and northeast faces), and the particular exposure of these premiers and grands crus, their specific climate and soils, are particularly resistant to global warming.”

7. Increase phenolic levels

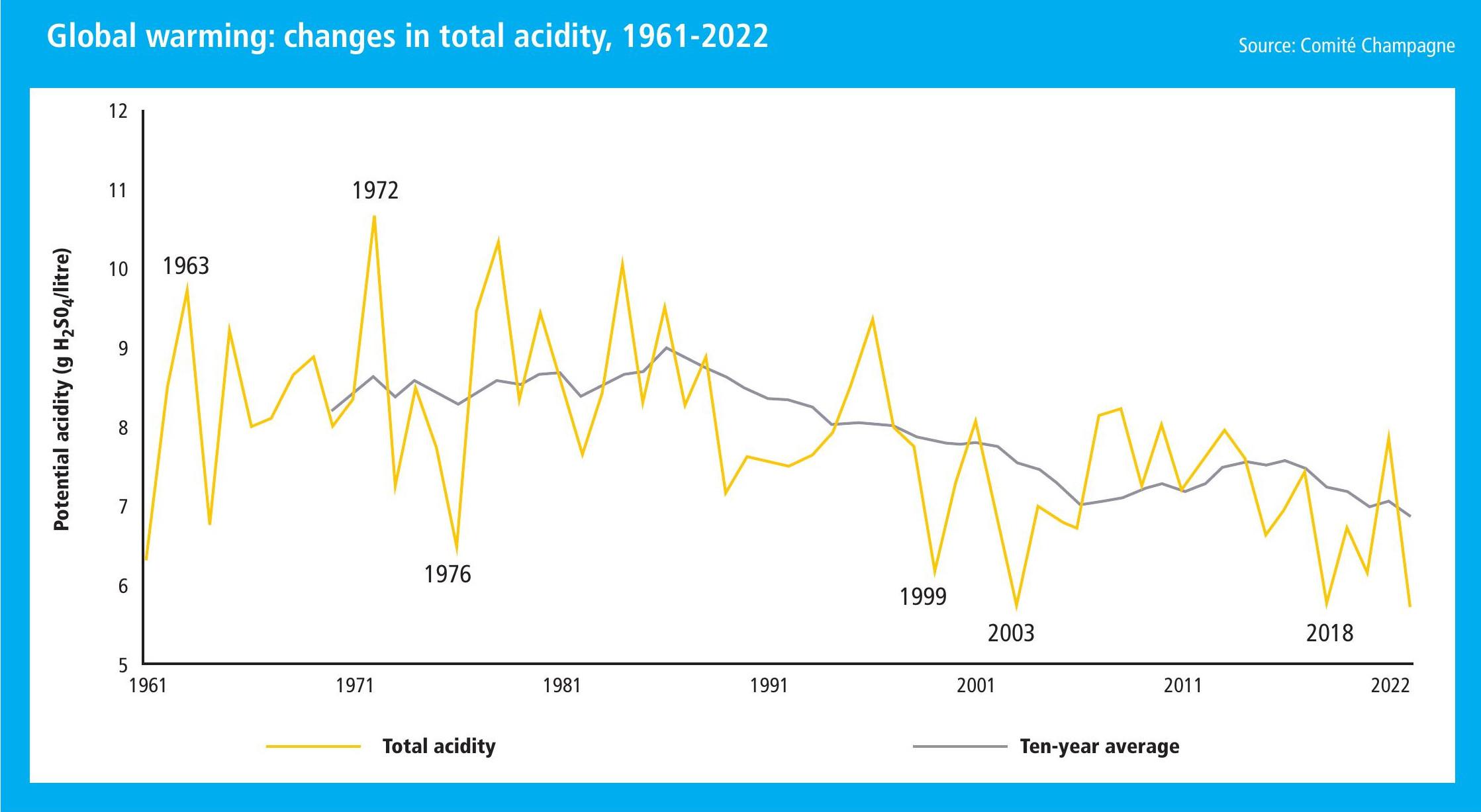

As for the winemaking, cellar masters appear to be looking for ways to ensure that Champagne retains an impression of freshness, even if acidity levels are lower in the wines (and down on average by 1.3g/litre over the past 30 years, according to Bollinger ’s Bunner).

To do this, one technique is to increase the level of phenolics in the wine. When elevated, these bring a dry and gently bitter sensation that produces a pleasant, mouthwatering sensation. It’s also a development that riper grapes appear to favour. Gouez explains: “What we are looking for is freshness – and that is not just acidity. There is another element that we didn’t discuss 20 years ago – and coming into discussion today – and that is bitterness.

“It is something new for Champagne: with maturation earlier in the season due to higher temperatures and higher levels of light, we are getting more aromas, more sugar and less acidity, which is for the better, because green Champagne doesn’t exist any more.”

Nevertheless, the decline in natural acidity is encouraging winemakers like Gouez to better understand how to extract bitter phenolics, which he says are like grapefruit, rather than pea-green. “Like red wines have rustic and noble tannins, in Champagne we want noble tannins that give a sensation of freshness,” he explains.

8. Block malolactic fermentation

There are other tools that a winemaker can employ to compensate for reduced acidity levels in Champagne. One often touted is preventing the conversion of sharp-tasting malic acid to softer lactic acid, a process that can be ‘blocked’ by the addition of sulphur dioxide, as well as keeping temperatures low and sterile-filtering the wine. Most cellar masters do seem to be at least experimenting with retaining malic acid in their wines, although an August heatwave can see the levels fall to such an extent that there isn’t much to keep. Furthermore, the conversion is beneficial for the wine, many producers believe. As Dom Pérignon’s chef de cave, Vincent Chaperon, tells db: “Today, we are still performing 100% malolactic fermentation – we still have many parameters in our hands today, and we don’t need to use this one yet, but we are experimenting. Malolactic fermentation brings complexity; it is another fermentation, and each one brings complexity for both grapes.”

A further approach sees winemakers reinstate oak casks for ageing a proportion of their wines. This is something that Ruinart’s Panaïotis has employed for his Blanc Singulier, a new, singleharvest, pure Chardonnay Champagne. Talking about the benefits of the material, he says: “We get a bit more structure from the oak, and a bit more tension to compensate for less acidity.”

9. Reduce the dosage

Such a Champagne as Blanc Singulier also draws attention to a further change taking place in the region to compensate for richer, riper styles of Champagne, and that is the reduction of sugar levels in the liqueur d’expédition – the final addition of wine, along with sugar and sulphur dioxide, after the disgorgement process to replace the lost liquid

In the case of Ruinart’s new cuvée, it is, in fact, the producer ’s first zero-dosage Champagne. Another name that’s also just released its inaugural ‘brut nature’ is Moët, with its new flagship label: Collection Impériale Création N°1. But the house has also been dropping the sugar levels in its Brut Impérial – Champagne’s best-selling product. Gouez tells db that he has cut the dosage by almost half over the past 20 years, from around 13g/l to 7g/l today, “and we are working on lower”, he says. His Grand Vintage has also seen sugar levels fall, from 11g/l to 5g/l, while the next release may be as low as 3g/l.

However, in reference to his category-leading brut NV, he says: “We have a natural richness in our wines, which comes from the grapes and reserve wines – we have much more reserve than in the past – and the wine spends longer on its lees in our cellars, so it doesn’t ask for that much dosage.”

10. Expand the reserve

As for the issue of reserves of wine from previous vintages, this has to be Champagne’s greatest insurance against the impact of climate change. Not only does a large store of wine provide a guarantee of supply if a harvest is struck by a weather-related problem, be it frost, hail, drought or moisture-induced mildew, but this back-up supply gives a range of wine styles to balance the variable character of the most recent harvest, known as the base wine.

Importantly, rules around harvesting in Champagne encourage producers to build up reserves. Indeed, the maximum reserve level for Champagne has been increased from 8,000 kg/ha to 10,000 kg/ha, meaning that producers can hold the equivalent of an entire vintage in tank. However, the way in which this wine is stored is important. Michel Drappier explains: “We have invested in more oak tanks for our reserve wines, so over 50% is now stored in wooden foudres, because the wines kept in oak retain more freshness – and there’s not too much oakiness in the taste, because it’s such a big volume.”

He has also just completed an underground wine store for keeping reserves of wine naturally cool. “We dug a big hole in the côteaux and placed the stainless steel vats directly in the ground, with the temperature of the soil keeping the temperature low – so there is no need for air conditioning, and the reserve wines can be kept at a constant 10o C throughout the year.”

And Drappier, like others (such as growers R Pouillon & Fils and Bérêche & Fils, along with houses such as Jacques Selosse and Henriot, and co-ops, notably Palmer), is looking to keep some of this store of wine as a ‘réserve perpetuelle’, in other words a vast tank holding a blend of older harvests.

An increasingly common approach in the region, it’s also one that a famous name like Champagne Louis Roederer has made prominent. As its cellar master Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon announced in 2021, the maison has ditched its Brut

Premier NV, moving to a slightly pricier, multi-vintage entry-point to its range called Collection, which is a numbered cuvée with a slightly different expression each year, depending on the blend of wines used in its creation. At the core of the new cuvée is a réserve perpetuelle, which includes wines back to 2012, and which is refreshed annually with wines from the most recent harvest.

Motivating the change is a “fight for freshness”, says Lécaillon, who comments that the huge vat holding a blend of past harvests was a better way to prevent oxidation than storing wines from different vintages separately in smaller tanks.

Indeed, this development, and the others noted above, draw attention to the reason why Champagne is the global benchmark for sparkling wine quality, despite changing weather patterns – if producers are not adapting practices in the vineyard, they are coming up with creative solutions in the cellar.

Related news

Champagne Duval-Leroy passes the baton with special releases