English still wine has the potential to rival sparkling

English sparkling may not be the grande dame for much longer, with the country’s still wines catching up fast, reports Gabriel Stone.

WHEN THE first wave of English wine swept in, success was built on a very clear, seductive premise. The chalk, the cool climate, the fizz, the grape varieties, the price tag, even a few handy investors from Reims: it all added up to a beautifully brazen riposte to Champagne.

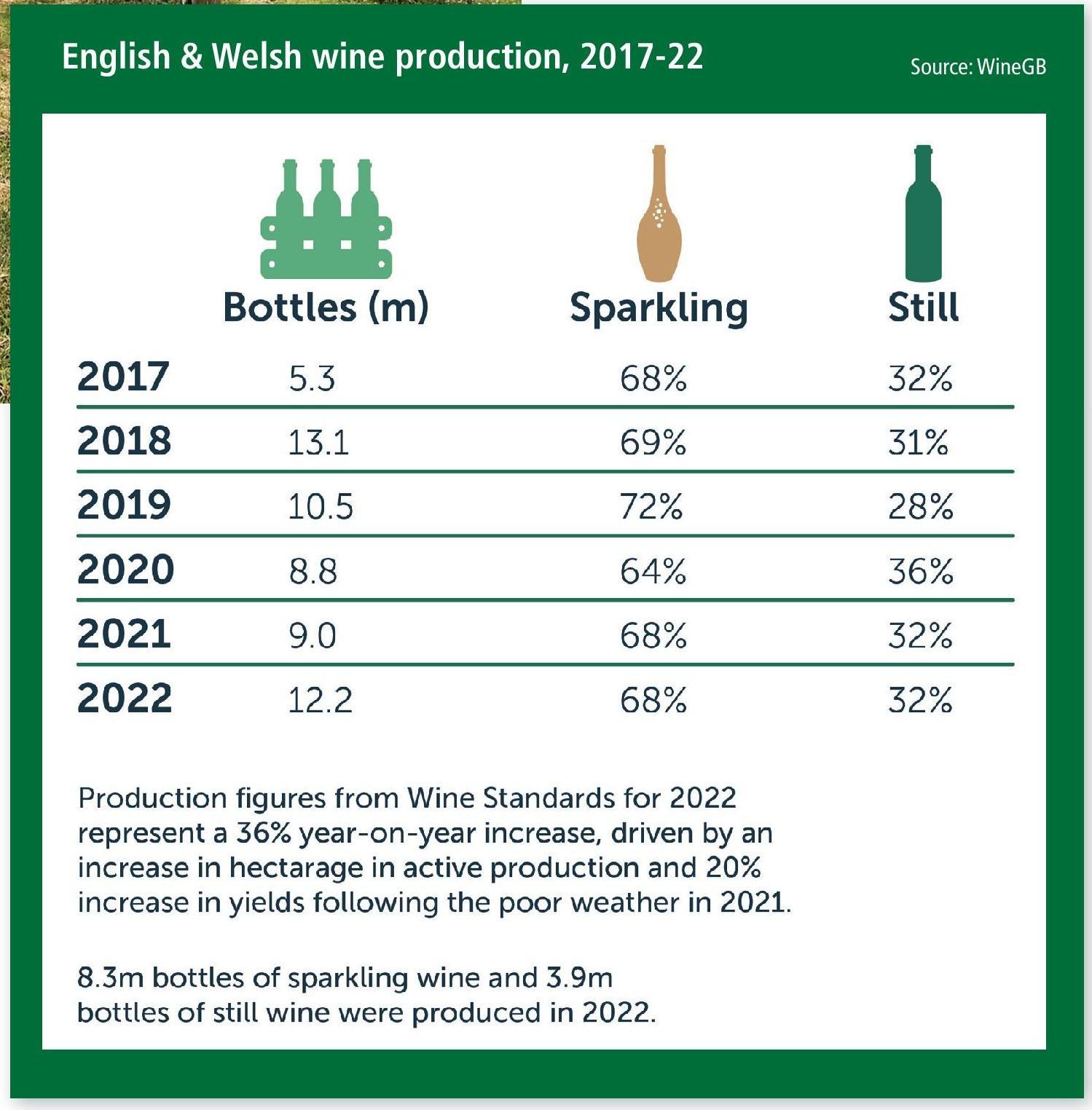

Still wine was always part of the story too, of course. Even as production boomed from 5.1 million bottles in 2015 to 12.2m bottles in 2022, still wine held onto a steady third of that total volume. Yet the image of English wine remained dominated by a medley of unfashionable German workhorse varieties, which couldn’t even draw on a flattering veil of CO2 and dosage to soften the effect of England’s notoriously capricious summers. This inconsistency of both style and quality, generally at prices that far exceeded those of your average Chilean Sauvignon Blanc, made it far easier for everyone to focus on the sparkling side of the success story.

As English fizz stylishly infiltrated Glyndebourne opera house, Royal Ascot race course and various state banquets, still wines struggled to shake off that awkward association with the days when English wine was at best an eccentric hobby, with still wines remaining the butt of a joke.

Well, they’re not laughing now. In fact, these days the unlikely words “Essex Chardonnay” are spoken with something close to reverence. London clay may not have quite the same ring as South Downs chalk, but it turns out to be rather good for ripening grapes, especially when combined with a relatively frost-free, dry climate that has long made the east of England such an important arable hub. It’s not unusual to find wineries as far west as Devon or Cornwall buying Essex fruit, but the county’s reputation has soared in recent years, thanks to the success of homegrown producers such as Danbury Ridge and Althorne Estate.

Last year saw a significant vote of confidence in Essex when US firm Jackson Family Wines, whose sprawling international portfolio includes such respected names as Yangarra in McLaren Vale and Napa Valley’s Cardinale, announced that Crouch Valley, located south-east of Chelmsford, was next on its shopping list. While the planned Chardonnay and Pinot Noir vineyards will also produce sparkling wine, the company confirmed that still wine forms a major part of the agenda.

It’s not just the Americans who see reasons to be excited about English still wine. Kent producer Simpsons Wine Estate planned for still wine to be a significant part of production when selecting clones for its first vineyard back in 2014. It was also still wine that led Simpsons’ early export push into Norway, a market that now accounts for one-quarter of its sales. In fact, suggests co-owner Ruth Simpson: “They are more advanced in their acceptance of English stills than our own home market.”

Once again, it has been Chardonnay and Pinot Noir driving this success. Indeed, Simpson reports that the estate’s Gravel Castle Chardonnay recently displaced “a well-known Chablis as the best-selling still white wine in the monopoly shops”.

If Champagne is a flattering reference point for England’s sparkling producers, it appears that many still producers are now courting comparison with white Burgundy. That parallel certainly needs to be a convincing one when your Chardonnay and Pinot Noir are priced at £40 a bottle, as is the case at Gusbourne. A leading light of the English sparkling wine revolution, this Kent-based producer now sees a real opportunity to ramp up the still side of its portfolio.

“The 2022 vintage was our largest ever bottling of still wine from one vintage,” remarks Gusbourne CEO Jonathan White. Although still wine currently represents less than 10% of production at Gusbourne, that’s set to change.

“Our future planting plans are much more focused on still wines than would have been the case five years ago,” confirms White. “There aren’t many producers around the world who have a leading reputation for both still and sparkling wines, so it’s quite exciting for us.”

Gusbourne is determined to ensure that still wine expansion aligns tightly with its high-end emphasis. “We very much focus on ‘fine wine’ grape varieties,” insists White. “You can make great Bacchus or Pinot Gris – even Albariño – and I’m sure it’s fascinating and delicious but, for us, those wines are more commonly associated with everyday drinking.”

Another sparkling-centric producer inspired by the still wine potential of 2022 is Langham, which has just released a limited, 1,143-bottle run of Chardonnay from its Bowling Green Vineyard in Dorset.

“Although our main focus is to constantly improve the quality of our sparkling wines, occasionally an opportunity arises to craft a beautiful still wine,” explains head winemaker Tommy Grimshaw. “The warm 2022 vintage gave us the perfect chance, so we had to take it up.”

Burgundy may have provided some of the used barrels but, right down to the label’s design tie-in with local sculptor Simon Gudgeon, this is a wine that is proudly from Dorset. Even so, fans of serious Chablis might find a good swap in this vibrant style, made from grapes grown on similarly Kimmeridgean soil. Even better, only 20 miles away lies Kimmeridge Bay itself, source of the fresh crab that would round off a thoroughly pleasant English experience.

In Hampshire, Black Chalk CEO Jacob Leadley reveals that still expressions formed no part of his original plan, back at the time of this producer’s maiden 2015 vintage. “It seemed like a distraction for a sparkling producer to make still wine,” he remarks. In 2020, new vineyards came his way including some Pinot Précoce and Pinot Gris, neither of which felt like a good stylistic fit for the Black Chalk sparkling range.

With joint winemaker Zoë Driver, Leadley decided to co-ferment these grapes and bottle them as a still rosé for the cellar door. The enthusiastic reception “opened my eyes a little bit to the fact that this was something England could produce regularly and consistently, and that it was a good extra product for us to have”, says Leadley, who adds: “It’s also relatively easy to make.”

When a grower friend rang in 2022 to offer Chardonnay grapes from a vineyard in Kent, Leadley’s interest was piqued, and another still wine joined Black Chalk’s portfolio.

Photo courtesy: Kay Ransom

Partner Content

Backing bacchus

But would Leadley’s increasingly openminded approach to English still wine extend to the likes of Bacchus? After all, for many people this early-ripening, aromatic, German-bred grape continues to act as England’s still wine flagship.

Look beyond the three fashionable Champagne grapes and Bacchus is this country’s fourth most widely-planted variety, immediately followed by the equally obscure Seyval Blanc, Solaris and Reichensteiner. That suggests a certain level of, if not fashionability, then at least solid commercial appeal.

“Slightly controversially, I’ve always wanted to steer clear,” says Leadley. “I’ve never enjoyed them as a wine drinker and I’ve never enjoyed working with them as a winemaker either. I’m not trying to dismiss other people’s attempts, but for me personally I don’t feel they have a huge future here.”

That’s not a view shared by the team at Stopham in West Sussex, which has championed English still wines ever since its first harvest in 2010. Today, 85% of production from this 17-acre estate is still. Marie Davies, sales & marketing manager at Stopham, describes aromatic still white wines as “a personal passion” for founder and winemaker Simon Woodhead. “But it also gives us a point of difference,” she adds.

As many winemakers seek to add an extra dimension to Bacchus with barrel fermentation or extended skin contact, Stopham believes simple stainless steel vinification offers the most attractive expression of this grape. “We’re dealing with such delicate, floral aromatics that to mask them with oak would just be sinful,” insists Davies. “If you like a crisp Sauvignon Blanc from the Loire, then you’re going to love it.”

Down in Cornwall, Knightor offers two very different Bacchus expressions: one in a similarly classic vein to Stopham; the other – Mena Hweg, Cornish for “sweet hill” – an off-dry style that tastes likes a lively mash-up between Mosel Riesling and Moscato d’Asti. “We’re bound by the climate, but we’re not bound by tradition,” remarks Knightor sales manager Liam Matthews. “That allows us to make whatever we want.”

It’s a mindset that is well illustrated by Knightor’s sprawling, adventurous portfolio of wines, 70% of which are still expressions. This includes excitingly original styles such as Trevannion – a spicy, rose-scented blend of Siegerrebe and Seyval Blanc blend that would appeal to fans of Gewürztraminer from Alsace.

While the producer has around 15 acres of its own vineyard, neither this modest scale nor the distinctly damp Cornish weather constrains ambitions here. Knightor buys in grapes from everywhere from Gloucestershire to Essex, including Riesling, Muscat and Sauvignon Blanc, all of which would be difficult to ripen reliably in Cornwall. “Riesling reaches the point of being able to be used as battery acid,” Knightor owner Adrian Derx wryly observes.

The winery even produces a Merlot/Cabernet Sauvignon from fruit grown in polytunnels. “We can sell it no problem at £25,” remarks Derx.

Another, rather less incongruous success story is a Pinot Précoce rosé from Knightor’s own Portscatho vineyard. It’s not difficult to see the appeal of this style on a sunny summer’s day for the many tourists who flock to Cornwall’s scenic south coast.

Another showcase for the diversity of England’s still wine scene is The Wine Society’s catalogue. A notable champion of English wine, the retailer currently lists around 15 still expressions that span the full regional, varietal and colour spectrum. Matthew Horsley, English wine buyer at The Wine Society, reports “a real thirst for English wine” among members. What’s more, the appeal is broad. “Our best-selling English white is under £10, and that’s a plethora of hybrids in a blend,” he comments. Echoing the perspective of many producers with a keen eye on cash flow and the bottom line, Horsley observes: “Hybrids are more consistent – you need to spray less; they’re a very interesting part of the puzzle. They don’t typically need oak and they can be released early.”

When it comes to Bacchus, Horsley tempers his enthusiasm with a price caveat. “I do believe in Bacchus, but as soon as it goes over £15 it’s dead,” he asserts, conceding Chapel Down’s £35 Kit’s Coty Bacchus as the sole present exception to this rule.

That’s not to suggest that Wine Society members don’t have an appetite for more expensive English fare. “When the best stuff comes in, it goes pretty quick,” confirms Horsley. “A recent offer of Danbury Ridge sold out in a few days, and that’s not cheap wine – and we bought quite a bit of it.”

For anyone scarred by a dire English still wine experience, it’s worth noting Horsley’s upbeat assessment of the rapid quality improvements he has seen in just the last few years.

“A lot of these producers are new to it,” he explains, and this inexperience is coupled with the “pretty serious curve balls” hurled by England’s reliably unreliable climate. Against such a testing backdrop, Horsley concludes: “It is exciting to see the wines improve year on year.”

If you prize consistency, sub-£10 prices and a style reminiscent of Barossa Shiraz, then English still wine is tricky to recommend in good faith. But, for anyone prepared to do their homework, embrace cool-climate character and be realistic about price point, this small category is a real hotbed of excitement. What’s more, there’s an electric sense that the story has only just begun.

Related news

Wine Origins Alliance welcomes two new members