Friends with benefits: How important are French varieties to Spanish wine?

French grape varieties occupy an important place in Spain’s winemaking heritage, but how do they co-exist with the country’s indigenous varieties? Lucy Shaw reports.

WITH JUST shy of one million hectares of vines in the ground across its 70 DOs, Spain boasts the largest area of land under vine in the world, in which a colossal number of grape varieties – some estimates put it at as many as 600 – are thriving in the country’s dramatically different climates and terroirs.

Taking the learnings of their ancestors and marrying them to the latest cutting-edge technology, Spain’s new guard of winemakers has been busy hunting down unique parcels of land where the alchemy of soil, climate, aspect and native grapes is helping them to produce wines of compelling complexity and a distinctly Spanish stamp, from old-vine Monastrells in Jumilla to ethereal Garnachas from Sierra de Gredos.

This fusing of old and new is to be applauded. Wines made from native grapes offer a heightened expression of time and place, but that’s only one side of the story in Spain. It’s the narrative most wineries want to push, particularly in our era of conscious consumption, where rarity and authenticity are the new signifiers of luxury. But, as wine consumption continues to fall around the world, the need to attract and retain newcomers to the category has never been greater, so we’re seeing a renewed interest in working with crowd-pleasing French grapes in Spain, with Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc leading the charge, alongside Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Viognier, Pinot Noir and Petit Verdot.

The question is: can these two vastly different approaches to winemaking happily coexist in Spain, or is it sending out mixed messages?

With such a broad palette of native grapes to choose from, it seems strange that Spanish winemakers would even entertain the idea of growing French varieties, but the practice isn’t as strange as it might seem.

DOP Somontano, in the northern Spanish province of Huesca, lies close to the French border and has championed the country’s varieties since the late 19th century, when the Lalanne family upped sticks from phylloxera-ravaged Bordeaux to pest-free Somontano, taking their Cabernet, Merlot and Chardonnay vines with them.

According to Mª Elisa Río Campo, director of communications for DOP Somontano, regardless of grape variety, “freshness, balanced acidity and aromatic intensity are the hallmarks of Somontano wines”, due to the influence of the nearby Pyrenees. While the majority of these wines are enjoyed at home in Spain, they are proving a hit overseas too due to offering a Spanish twist on French classics.

French grapes account for the majority of plantings in Somontano, unusually for a Spanish region, and Río Campo reports that Chardonnay and Gewurztraminer plantings in the region have “risen significantly” recently due to a growing global thirst for Spanish whites.

For José Ferrer, chief winemaker at Viñas del Vero, more than 130 years of French grape cultivation in Somontano has helped the varieties to become perfectly adapted to the terroir, leading to “honest” wines with “fuller aromas, rounder palates and unequivocal typicity”.

He says: “Our Sauvignon Blanc is more similar to those from the Southern Hemisphere than France, while our Syrah is more akin to those from the Rhône, and our Pinots produce elegant rosés that reflect the delicacy of the variety.”

DIFFERENCES IN CHARACTER

Jesús Artajona, chief winemaker at Enate, admits that making a hero of French grapes was beneficial in getting the winery’s name out there.

“International varieties helped us to improve our image and gave us visibility,” he says, revealing that picking over a number of days leads to notable differences in character.

“Our earlier-picked Chardonnay has notes of lemon, lime, green apple and nervy flavours, while the late-picked grapes are richer, with peach and apricot aromas.”

As for Syrah, Artajona works with both French and Australian clones in two separate plots. “The ‘French’ plot is a terraced vineyard on sandy soils that delivers a softer, fruitier and fresher wine, while the ‘Australian’ plot is on a very steep slope with rocky soils that offers a more spicy and structured wine with more ageing potential,” he explains. “The final blend is somewhere in between.”

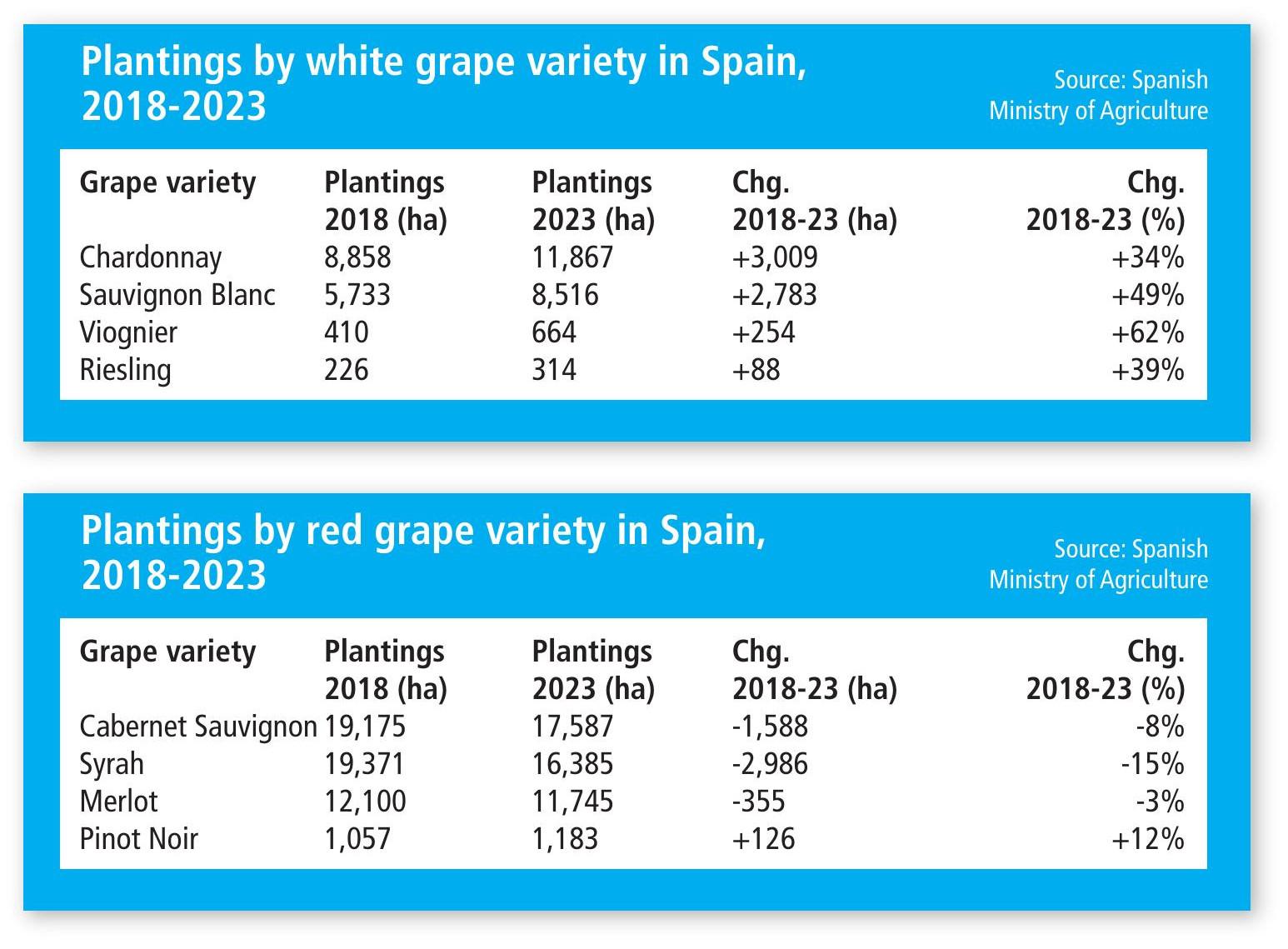

Reflecting the growing thirst for Spanish whites, plantings of Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and Viognier are on the rise across Spain, up by 34%, 48% and 62% respectively since 2018, according to the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture. The trio have found a happy home in the northern region of Rueda, which relaxed its planting rules in 2020 to allow for the addition of Chardonnay and Viognier within its blends.

“This decision was made to give wineries more flexibility and freedom, so that each can find their own identity,” says Santiago Mora, head of Rueda’s regulatory council. While native grape Verdejo still accounts for the lion’s share of plantings, single-varietal Sauvignon Blanc is going great guns in the region, and is being lapped up by consumers the world over.

“The impressive adaptation of Sauvignon to our soils has complemented the prominent position this variety holds in our portfolio. Demand for our Sauvignon Blanc has been so high at times that we’ve needed to allocate it to our customers,” reveals Elena Martín Oyagüe, technical director at Rueda’s Bodega Cuatro Rayas. She explains that working with Sauvignon Blanc has allowed the winery to reach a broader range of consumers.

Fitting in: Sauvignon Blanc has adapted well to Rueda, says Elena Martín Oyagüe

Meanwhile, Sara Bañuelos, director of Ramón Bilbao’s winery in Rueda, says the “iconic” grape variety is helping to create “elegant single-varietal wines with herbal and tropical notes, and complex blends with wonderful freshness and aromatic intensity”.

Having branched out from Rioja to Rueda, Cristina Forner, director of Marqués de Cáceres, is happy with how her Chardonnay is performing in the region. “It has adapted perfectly to Rueda’s pebbly soils,” says Forner, who vinifies part of the wine on its lees in both French oak and concrete eggs. The result, she says, is a “complex and structured wine with toasty notes and refined acidity”.

Chardonnay is also being championed in Navarra by Chivite, which has worked with the French grape for more than 30 years. A perfect alignment of orientation, climate and free-draining soils “created a sanctuary for Chardonnay, yielding elegant wines with typicity, complexity, remarkable acidity and excellent ageing potential”, says Chivite’s chief winemaker, David González, who feels that transmitting the character of a place is more important than working with native grapes.

“What matters most is that wineries capture the unique essence of their region, whether that’s through indigenous or international grapes,” he says.

Working with Champagne grapes Chardonnay and Pinot Noir isn’t without its challenges for Meritxell Juvé, CEO of Cava producer Juvé & Camps.

“The climate and soils in Penedès differ greatly from those of the Champagne region, creating Chardonnay and Pinot with much more concentrated aromas and flavours, but less acidity, meaning we have to bring forward the harvesting of these grapes to preserve their freshness,” Juvé reveals.

In Rioja, plantings of Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc are on the rise due to increasing global demand for the region’s whites. Bodegas Ysios’ winemaker, Clara Canals, is experimenting with Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc to see how they perform in local soils.

“The vineyards are around 10 years old and the idea is to explore their expression in our terroir. Before selling the wines, we want to be sure that they reflect something unique from our land, as that’s our philosophy,” she says.

Partner Content

THE RED FRONT

On the red front, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah are being used to great effect in blends across Spain to help indigenous grapes like Tempranillo and Monastrell to sing.

“The greatest advantage of these French varieties is as a blending component and complement to Spain’s native grapes, as they provide complexity, structure, longevity and freshness,” says Javier Galarreta of Araex Grands.

For Penedès pioneer Familia Torres, planting Cabernet Sauvignon in 1964 for the production of its now iconic Mas La Plana wine was a no-brainer, given how highly regarded the grape was around the world.

“At the time, everyone looked to Bordeaux and Burgundy as their reference points,” explains Mireia Torres, director of innovation at Familia Torres. “My father planted French varieties because they were what consumers were asking for.”

She also shines a light on French varieties at Jean Leon in Penedès out of loyalty to the winery’s eponymous founder, who couldn’t afford a French château, so bought a bodega in northern Spain instead.

“Single-vineyard wines made with French varieties such as Chardonnay, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc are part of Jean Leon’s history, and my aim is to keep the promise my father made to the owner,” says Torres, who reports that Petit Verdot is proving particularly resilient to climate change in Penedès. And therein lies the rub.

As commercially successful as Spanish wines made from French grapes may be, surely it will be varieties that have spent centuries adapting to the country’s climatic conditions that will prove best-equipped to cope in our warming climate?

While Petit Verdot might be thriving in the heat, Merlot isn’t faring so well in Spain. “After three years of persistent drought, Merlot yields have dropped considerably, so winegrowers are replacing these vineyards with more heat-resistant grapes,” reveals Torres.

In Rueda, Sauvignon Blanc yields have been more negatively impacted by the recent drought than native grape Verdejo.

“We’ve noticed Sauvignon Blanc is more sensitive to climate change than Verdejo because Sauvignon is a more delicate variety with a thinner skin. Over the past few years it has been ripening faster and yields have decreased slightly,” says Elena Martín Oyagüe of Cuatro Rayas.

Is local the ultimate expression of luxury?

José Urtasun, co-owner of Bodegas Remírez de Ganuza in Rioja Alavesa, believes Spanish winemakers used to look to France for inspiration, but now have the confidence to create something unique and interesting with their own grapes.

“Spanish chefs like Juan Mari Arzak learnt the techniques and skills from French chefs and used them to update and elevate Basque gastronomy. A similar thing has happened in wine – we’ve learnt from the best producers in France and are using this knowledge to adapt and enrich our own winemaking heritage and identity, and to promote our diversity around the world,” Urtasun says.

“In the globalised world we live in, local products have become the ultimate expression of luxury.”

Richard Cochrane, managing director of Félix Solís UK, has noticed a similar pattern.

“Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay are facing the more immediate impact of climate change,” he says. “Strategies to mitigate this, such as earlier picking, can certainly help, but as the 2023 vintage showed, yields and acidity levels dropped more for these two varieties under similar management than the indigenous grapes.”

With such a vast area of land under vine in Spain, there is room for native grapes and international varieties to flourish, as they both currently serve a purpose.

“Indigenous varieties remain the best adapted to Spain’s viticultural conditions and retain by far the biggest footprint of vineyard area, while international grapes help to introduce new consumers to Spain, where nervousness about unknown varieties can be off-putting,” says Cochrane.

Chema Ryan Murúa, head winemaker at Muriel in Rioja, agrees: “The cohabitation of autochthonous varieties alongside international ones is necessary, as it provides greater diversity in Spanish wines and illustrates the huge potential our country has as a producer,” he says.

However, not all wine producers see the merits of French grapes growing in Spanish soils.

“We shouldn’t make the mistake of trying to imitate what is done in other countries, but should instead strive to extract the personality and identity that is inherent in our terroirs,” argues Santiago Frías, president of Bodegas Riojanas.

“Trying to compete in the international market against well-established producers of French varieties, when we’re unable to offer a point of difference, would leave us in a vulnerable position.”

Rubén Gil, manager of DO Toro’s regulatory council, is equally wary of apeing France.

“Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Cabernet and Merlot aren’t what the consumer expects or wants from Spain, so we should keep investing in native varieties,” he says. “That’s what makes Spanish wines special and unique. Wines made from international varieties can be soulless and lacking in personality, because they’re grown in so many different parts of the world.”

While opinions are divided, French grape varieties still have an important role to play in Spain, in dangling the proverbial carrot and enticing cautious consumers into the category. But it’s once they are over the threshold and starting to explore Spain’s kaleidoscope of native grapes, from apple-scented Godellos made in Valdeorras to perfumed Mencías from Bierzo, that the magic really begins to happen.

Related news

VIK 2022: ‘the beginning of a journey toward self-sufficiency’