When it comes to Champagne does ‘older’ mean better?

Releasing back vintages of Champagne was once a rarity, but the practice is becoming increasingly common now, as Giles Fallowfield discovers.

OPPORTUNITIES TO taste, let alone drink, older, previously released vintages of Champagne used to be few and far between. Back in the early 1990s, when I started making regular visits to the region, it only ever happened when you were there, in situ, in the cellars of certain houses or of a tiny number of top grower producers. And the winemaker – because they were usually the people who opened such treats to show to interested guests – wanted to have a good idea that you might appreciate the experience.

There were practically no commercial re-releases of older vintages that had been given extra time on their lees, and precious few bottles were kept back for extra ageing on the cork after disgorgement.

A new vintage was put on the market at some point after perhaps five to 10 years’ ageing, and it was on the market until it was all sold – after which the producer moved on to the next vintage release.

If there was a large gap between declared vintages – for example, few houses made much vintage Champagne between their 1990 releases and 1995, the next widely released year – then the follow-on vintage release was likely to have less cellar age, irrespective of what the particular characteristics of that year might be.

It is hard to put a finger on precisely when this attitude changed, because that change only took place gradually. But even today, when it appears there are enough knowledgeable and interested consumers to understand, appreciate and buy such wines, only a small number of producers have such a re-release programme.

While more houses, plus a sprinkling of top co-ops and growers, do regularly put some vintage wines away for longer cellaring, they may not do so in ‘commercial’ volumes, and as a result few outside the wine trade and a handful of journalists ever get to taste such wines.

Starting up a commercial programme of putting aside a percentage of any given vintage – in modern times, vintages may be declared six or more times a decade – also requires a brand owner to have the financial strength to support such a programme, and needs someone with the necessary decision-making power to feel it is a step that it’s important to make.

This was not an idea that found wide favour in Champagne even as recently as 15 years ago. However, the wines that certain pioneering houses did put away for longer ageing attracted increasing interest and admiration from their peers in the small winemaking community and, importantly, from informed critics. So much so that today it doesn’t seem like a commercially risky thing to do, for anyone making vintage wine a central part of their offer.

This change in attitude has been greatly helped by leading producers increasingly marketing vintage Champagne as “great white wine” – not just fizz.

OBVIOUS CANDIDATE

Pol Roger, a house for whom vintage Champagne represents around one quarter of its business – as opposed to the Champenois average of around 8% – is thus an obvious candidate for such a programme.

The news that, as part of its 175th anniversary celebrations in 2024, it is going to start re-releasing some vintage wines aged for two decades or more, shouldn’t therefore come as much of a surprise – especially as Pol has a reputation for making vintage Champagne that ages exceptionally well for longer periods, given good cellaring conditions – an important caveat.

The logic for Pol Roger CEO Laurent d’Harcourt is that such a programme “allows us to give the opportunity to people who don’t have a cellar at home, to try wine originally shipped 10 to 12 years ago, that has been given extra age in our cellars in perfect conditions”.

The first six such Vinothèque wines – 2002 and 2000 Brut Vintage; 2000 Blanc de Blancs Vintage; 1999 Brut Rosé Vintage; plus the 1999 and 1998 vintages of Cuvée Sir Winston Churchill – are all from the original disgorgements, and will have the date of that disgorgement, and other salient details, printed on the back labels.

“We are only talking hundreds of bottles, not thousands, available for the whole world,” says d’Harcourt.

He sees 10 years’ extra age for straight vintage, and more like a dozen for Churchill, as the optimal time for the wines to show considerable additional textural complexity and development – or, as he puts it, “power and freshness in perfect harmony”.

The disgorgement dates are the final ones for the original releases of these wines, he says (typically there might be several disgorgements over the 12-18 months when the wine was originally sold, according to demand and depending on the volume of the vintage produced) – so, for example, for 2000 Brut Vintage the disgorgement date is 22 November 2011.

The idea, explains d’Harcourt, is that there will be a similar number of such wines released every two years, with the 2004 vintage wines and 2002 Churchill put on the market in 2025.

But, before that happens, he says: “We want to see if the market is accepting the idea. We are already selling some back vintages, but not with any detailed information about the release, and so this will be a new departure when the first six Vinothèque [wines] are released in early February next year.

That release will coincide with the formal opening of the refurbished Pol Roger production facility in Epernay in March 2024, a four-yearlong project that has transformed and “future-proofed” the site, according to d’Harcourt, with new bottling, disgorging, labelling and packaging lines now fully operational, and the landscaping nearing completion.

If further proof of vintage Pol’s ability to age gracefully post-disgorgement were needed, after tasting all the re-released vintages, we are treated to a vintage from the 1920s that the house still has a few bottles of: the glorious, still amazingly fresh, 1921 – Sir Winston Churchill drank up all the stock of 1928, the other great 1920s vintage, in his lifetime.

Those re-releasing vintage Champagnes made more than two decades ago broadly fall into two camps. Given a choice – that is, if the wines put away for longer ageing were not disgorged – there are some producers who like to see extended lees ageing with a relatively recent disgorgement prior to sale, while others have a preference for longer post-disgorgement ageing under cork, before the wines are sold.

In reality, it’s less clear-cut today – and most would at least now agree that older wines need longer to recover from the shock of the disgorgement before release.

Rare finds: Perrier-Jouët back vintages are available from the house’s Epernay shop

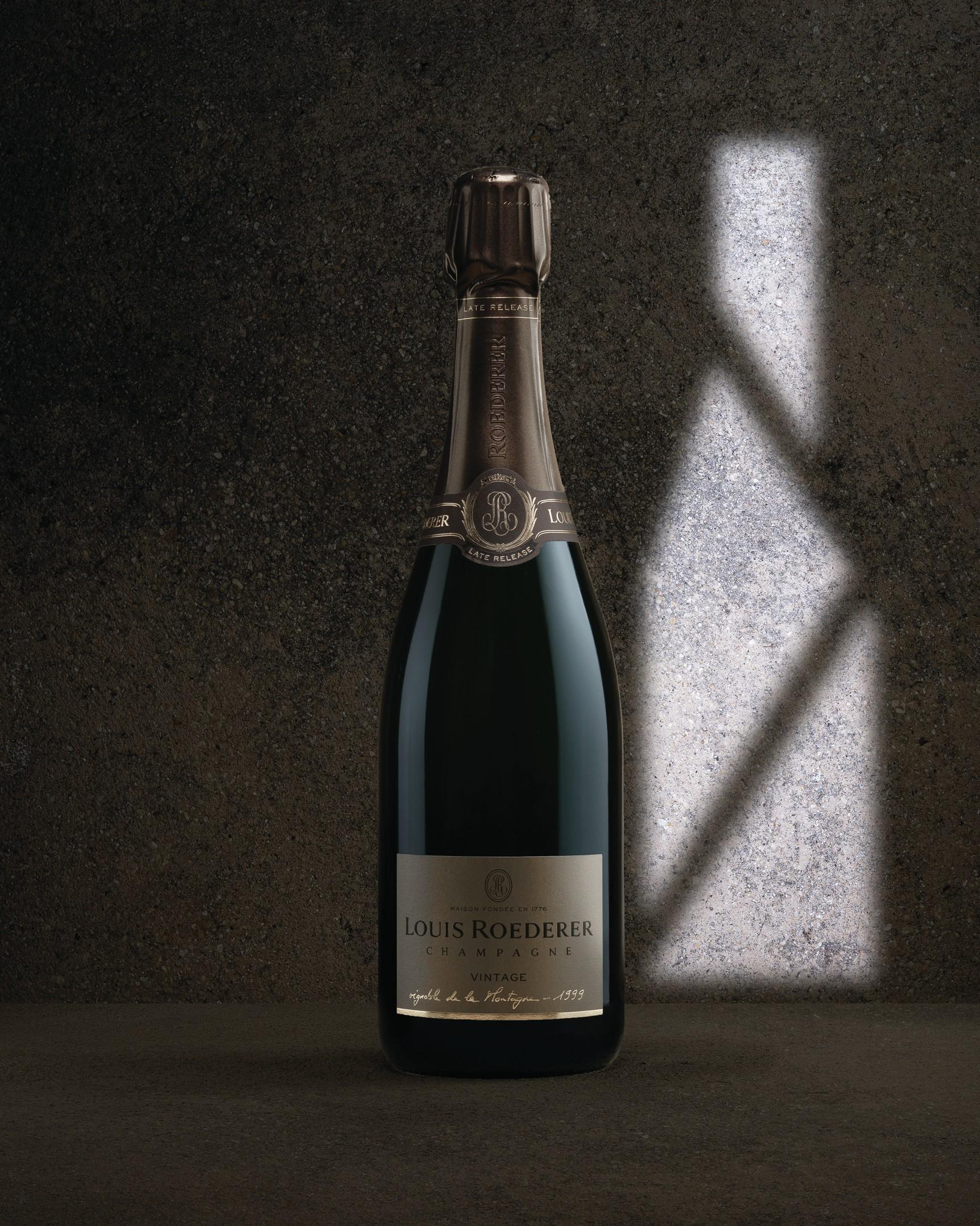

At Louis Roederer, Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, head winemaker since 1989 – and the date is significant – has gone down a similar route to Pol Roger of longer post-disgorgement ageing for the five Roederer vintage wines from the 1990s that he introduced in the UK at a tasting in November 2022.

His presentation revolved around the long post-disgorgement ageing under cork of these vintage Champagnes, all shown in their original disgorgements.

Even though he had only just started working there, it was Lécaillon himself who had the foresight to put these wines away. And it was his choice to disgorge them.

“They didn’t keep any stock of vintage releases when I started, so I put some vintages aside to showcase their ageability,” he says, adding that the company was always talking about the ageing potential of the wines, but without the proof to show people.

And Lécaillon was at some pains to point out at the launch: “This is not a vinothèque collection, nor a limited edition – nothing new, in fact, just a deep dive into our DNA.” In other words, a means of demonstrating the peaks of complexity that such wines could reach over time.

LONG LEES AGEING

Representing a different approach – long lees ageing but a short post-disgorgement period before sale – Bollinger, with its trademarked Récemment Dégorgé (recently disgorged or RD) vintage wines, can claim to be the first commercial exponent of re-releasing vintage Champagne at a later date.

Lily Bollinger introduced the first RD, from the 1952 vintage, in 1961. Since then, the wines have carried a disgorgement date on the bottle.

However, the concept of a library of vintage re-releases from a range of years or decades was first placed centre-stage by Moët & Chandon back in August 2003. At a very grand launch over two days at Moët’s Epernay headquarters, the highlight was arguably a dinner held at nearby Fort Chabrol, at which we tasted vintages from 1990, 1988 and 1982 in bottle, plus 1973 and 1961 in magnum, all of which were relatively recently disgorged.

Retail prices for this range two decades ago started at only £35.99, which tells you something about how little appreciated these wines were outside a core of Champagne lovers.

Moët has more recently released several ‘trilogies’ of its Grand Vintage Collection with a trio of wines that span three different decades – and The Finest Bubble has two previous incarnations still available: 2002, 1992 and 1982; plus 2008, 1998 and 1988 – but Moët has now refined the offer to the current 2015 Grand Vintage, plus 2006 and 1999, which were also very sunny, warm years in Champagne.

History boys: Palmer has older vintages spanning 1959-1999 on the market

SHOCK OF DISGORGEMENT

While there is near-complete unanimity in Champagne that wines stored on their lees retain freshness noticeably well, today more and more producers want a longer period of post-disgorgement ageing before any such venerable wines are put on sale.

This is partly about the shock of disgorgement, from which wines need longer to recover as they grow older (rather like elderly patients recovering from a serious hospital operation).

Bruno Paillard has been particularly vocal about this specific issue for many years, and it seems the consensus in Champagne has now moved noticeably in his direction over the past decade or so.

“The longer you keep Champagne on its lees, the more you increase its ageing potential,” says Moët & Chandon chef de cave Benoït Gouez.

“It’s like inoculating the wine, which is enriched by the long contact with the yeast cells,” he adds, explaining his belief that “the larger the format, the longer the lees ageing [should be]”. Gouez sees the sweet spot for disgorging bottles as “when you reach about 15-16 years of lees ageing, when you get a change in profile”.

To really understand the heights of excellence that Champagne at its best can reach, you have to experience how well vintage Champagnes can age – and these wines offer those who are interested the opportunity to do so. It’s an opportunity not to be missed.

Related news

Garcés Silva: fresh thinking from Leyda

Christie's to sell Burgundies from renowned British collector Ian Mill KC