Counting the cost: why producing Champagne is getting pricier

Champagne houses are facing huge hikes in the price of everything from grapes to cartons. The situation has been exacerbated by small harvests – and some businesses may go to the wall as a result. Giles Fallowfield reports.

THE COSTS of production in Champagne have soared since the pandemic first hit in the spring of 2020. The price of everything that is needed to make and market a single bottle has risen, from the glass container itself, right through to the muselet or wire cage with which the final cork is held in place. And the huge increase in the cost of energy needed at all stages of production – getting the grapes from the vineyard to the winery, elaborating the wine and then transporting the weighty finished bottles to market – has exacerbated the problem. However, despite all of these costs rising, some dramatically, the price of the grapes needed to make the wine still accounts for by far the largest proportion of the overall cost of any bottle of Champagne.

The Union des Maisons de Champagne (UMC), which represents the interests of most of the main négociants operating in the region, says grapes alone account for 36% of the average price of a bottle of Champagne and, according to UMC president David Chatillon, “this figure has been relatively stable over the past 10 years”. The figure is based on all the Négociant Manipulants (NM), including those that are not members of the UMC – producers who between them accounted for 73.03% of total Champagne sales in 2021 (72.8% in 2022). The average price of the bottles sold by the NM in 2021 was €19.06, says Chatillon. If we take the figure the CIVC uses for the volume of grapes needed to produce one 75cl bottle, which is 1.17kg, this means at least €8.02 was paid for the grapes in the average bottle.

However, the volume of grapes needed rises to just over 1.4kg if you are only using the first pressing (the cuvée), something that most well-known marques claim they always do. Then the price of the grapes needed to fill one bottle rises to €9.60.

(Under the Cahier des Charges, the rules that specify how Champagne is to be produced, from every 4,000kg marc of Champagne you are allowed to extract 2,050 litres of the cuvée and 500 litres of taille (second pressing); so you need about 20% more grapes if you are not using any taille in your blend). Of course, if a producer doesn’t use the taille, they will sell it to other producers or exchange it for juice from the first pressing – paying a premium or receiving proportionately less juice – so that second pressing ‘Champagne’ stays in the system.

When I asked Louis Roederer chef de caves Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon what figures they work from, he said: “Looking at the numbers, 4,000kg of grapes gives 20.5 hectolitres (hl) of cuvée juice and approximately 2,730, 75cl formats at bottling. This is 1.47kg per bottle.” While the volume of grapes needed may rise according to your production approach, the premiums that can be paid over the standard average price are numerous. Grape prices in Champagne used to be fixed each harvest as a result of a negotiation in late summer between the two main groups in the region: the houses, as represented by the UMC, and the main growers union, the Syndicat Général des Vignerons de la Champagne (SGV). The presidents of the UMC and SGV, also de facto co-presidents of the Comité Champagne, would be lobbied by their members in the run-up to each harvest and, taking those views into account, would then discuss and agree a compromise figure.

The level of yield also set by these parties, within the parameters allowed by the INAO, had influenced the price agreed. For growers selling all or most of their grapes to the négoce, their income is a product of the volume they are allowed to pick and the price per kilo paid. This was a massively contentious issue in 2020, when the négoce insisted, mistakenly – some would say foolishly – on a very low yield level, which in effect ruined the chances of many grower producers of doing business profitably.

The price per kilo agreed would be for grand cru grapes, that is to say those rated 100% on the Échelle des Crus. In turn, the prices in the contracts agreed between buyers (the négoce) and sellers (the growers) would be based on that price, with villages rated between 80% and 100% getting a proportionate amount of the price agreed per kilo.

This system worked well in the appellation for many years and, while it was true that the largest operators in Champagne had the biggest influence on the final price, a joint decision was made as a result of discussions between the UMC and SGV presidents, so other influences were bought to bear. Perhaps if yields had been very low in the previous year, because of disease issues or poor weather, the growers’ demand for more yield and/or better prices might be looked on more favourably.

However, in 2001, the EU decided that this system for setting grape prices was anticompetitive under EU rules and it was prohibited. Since then, the single largest player in Champagne and the biggest purchaser of grapes, Moët & Chandon, has in effect dictated what this price should be each year. And, while the Comité Champagne still publishes a price per kilo for grapes, it is an average based on transactions that have already taken place, rather than being the price on which transactions are based.

HOW CHAMPAGNE WORKS

When the price Moët & Chandon intends to pay per kilo becomes apparent, other big players in the market are not obliged to follow suit, but they tend to; this is how Champagne works. Fears that paying less looks bad and, importantly, that it might prompt growers not to renew supply contracts, are powerful influences on decision making.

In the current market turmoil following the négociants’ ‘own goal’ of the very low yield limit (8,000kg/ha) they set in 2020 and the small, disease- and frost-hit agronomic yield in 2021 (7,274kg/ha, equating to 210m bottles, far below the level of demand), everyone wanted the 2022 harvest to be generous in volume and high in quality, as demand has strengthened significantly since the start of the pandemic.

The 2022 yield was initially set at 12,000kg/ha with a provision to put up to a further 3,500kg/ha into the reserve, but this was later extended to 4,500kg, meaning that the maximum that could be picked totalled 16,500kg/ha. Partly due to the very dry growing season, the average yield achieved in 2022 was 14,055kg/ha (Comité Champagne provisional figure). This is still the largest yield achieved in the region for 14 years, since 14,231kg/ha in 2008 and, a year earlier, the all-time record of 14,242kg/ha in 2007.

The average price of one kilo of grapes in 2008 stood at €5.40, higher than the 2007 level of €5.11, despite the global financial crisis starting just as the harvest was being picked (see box, page 41). It fell to €5.25 in 2009, but since then has risen every year up to 2020, when the négoce somehow got away with paying less than in 2019 – €6.30 vs €6.36 – in the process cutting the growers’ income further, given the low 8,000kg/ha yield they had forced through. In 2022 it jumped to €6.75/kg, a rise of €0.39, by far the largest annual rise since the turn of the millennium.

This is the average appellation price, which does not reflect the premiums that are often paid – for continuity, quality and for farmers that are environmentally (HVE) or organically certified. Grand cru grape prices paid for both Chardonnay and Pinot Noir have in many cases been over €9/kg – and transactions even take place at €10/kg.

The prices per kilo to be paid for the 2022 crop are the highest ever, and the yield is near to the biggest too. This will result in by far the largest bill the négoce collectively has ever paid for grapes. This isn’t really a problem for the LVMH brands, including market leader Moët, and some other high-profile producers, because their selling prices are sufficiently high for them to still make a good profit. However, for those with less strong brands, and therefore lower selling prices, particularly those who have to buy in most or all of their grapes, the higher price presents a problem. It is very likely that some of the weaker companies, selling fairly cheaply or failing, as the mantra of the powerful négociants goes, “to add value”, may even be driven out of business altogether.

This is part of the strategy of the LVMH group, as previous CEOs of the market leader have conceded. They want to be able to buy more grapes to sell more Champagne and increase their dominance of the market. And as all the vineyard land that could be planted in the currently defined appellation is already planted and the long-term trend is for yields to decline, not increase – partly because of a more environmentally sustainable approach to farming the land, but also because of ageing vineyard stock – their only way of growing is by acquisition, or by taking a larger share of the grapes being sold each year to the négociants.

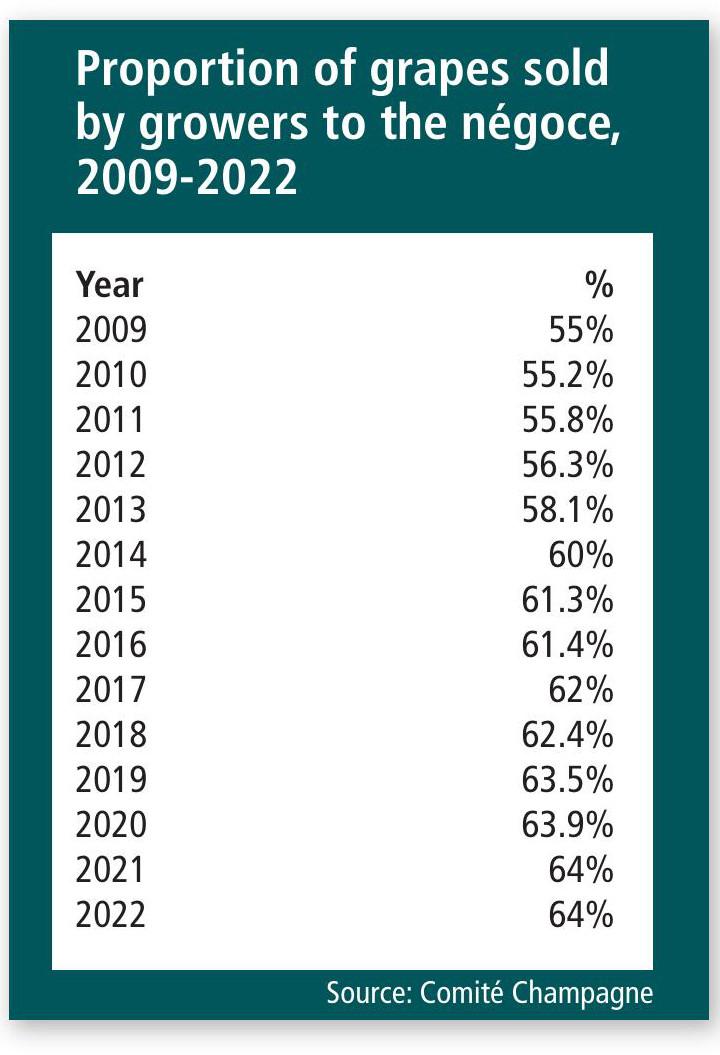

Higher prices for grapes, something which LVMH has consciously helped to create, have already led to an increasing proportion of the grapes produced in Champagne being sold to the négoce (see box, page 41). It has risen steadily from 55% in 2009 to 64% in the past two harvests (2021 and 2022).

Faced with a choice between getting well paid for their grapes within 12 months of picking them, or having to make their own Champagne, which has to be cellared for a minimum of 15 months, then promoted and sold over the next three or four years in an uncertain and highly competitive marketplace – more and more growers are choosing the former path.

The bill for grapes from the 2022 harvest is paid in four quarterly tranches. The first payment was made on 5 December 2022, the second on 5 March 2023, and the third and final payments are due on 5 June and 5 September 2023 respectively. The first payment also includes the cost of pressing, estimated at around €1/kg, so for a marc (pressing) of grand cru blanc costing, say, €10/kg, the bill would be around €44,000, with the first payment in December 2022 of €14,000. With a yield of 12,000kg/ha, the price of one hectare of grapes would be €132,000. To scale this up, a large négociant without much in the way of its own vineyards is looking at paying about €13.2m for 100ha of grapes, from which they could produce about 1m bottles of Champagne.

Partner Content

Given that Champagne sales boomed in the important last quarter of 2022, it is safe to assume that most négociants will be able to make the first and second payments for the 2022 harvest relatively easily. The crunch will come in June and September this year, when revenues from the first half of 2023 may not be looking so rosy – and therefore cash flow may become an issue. The rise in the price of all dried goods, amplified by higher energy costs, will increase the pressure on vulnerable producers. And interest rates on any bank loans have more than doubled in 12 months of war in Ukraine.

Bearing this in mind, it’s no accident that there has been a spate of sell-offs of Champagne businesses over the past 18 months or so. Two of the best-known, though on a different scale of production, are Jacquesson and Henriot, both bought last year by the Artémis group owned by the Pinault family. While a casual analysis might suggest Artémis could keep both houses, it has quickly ditched Henriot. Why the preference for Jacquesson? It’s all about vineyards and cost control.

VALUABLE VINEYARD

In the case of the Henriot group, Artémis was particularly after the valuable Burgundy vineyard holdings of Bouchard and William Fèvre. But in Champagne, a brand with little or no vineyard has to pay the market price for grapes, over which it has little control. As well as being a brand prized for its consistent quality, selling its wines at a high price point, Jacquesson’s 28ha of vines provides about 80% of its production needs. By contrast, the traditional Henriot vineyards were all sold to Veuve Clicquot when Joseph Henriot became president of Clicquot in the late 1980s. Owning vineyards and being at least partly self-sufficient in terms of grape supply has never been more important in Champagne than it is today. If you don’t have that, you need to be part of a sufficiently powerful group with wider interests. But, in both cases, in order to survive profitably you have to be selling your wines at premium prices – and that is now really the only path open to the Champenois.

Higher and higher: Champagne costs escalate

“We have seen steeply rising costs across almost all areas of input into a bottle of Champagne, with grapes, cartons, natural cork and electricity prices all increasing substantially,” says Alexei Rosin, managing director, Moët Hennessy UK.

He continues: “Sixty percent of the costs in a bottle stem from grape prices, including bottling and riddling. We have seen these increase at nearly 7% in 2022 versus 2021, with knock-on effects for 2023. Other elements, such as energy, metals, logistics, that make up a further 15% of the cost of a bottle, have also grown strongly. Electricity, for example, is up 300% versus last year and ocean freight up 600% since January 2020.”

The remaining 25% of cost comes from what Rosin calls “the continuous quest for quality, accelerating sustainable practices and brand desirability”. These figures are based on rising costs at Moët and Veuve Clicquot, by far the two largest brands in Champagne.

At Louis Roederer, chef de caves Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon estimates that “over the past two years, the cost of labour has increased by about 10%, while the rise in the cost of dry goods and energy is between 10% and 50%, although some shipment costs have been multiplied fivefold”. As for corks and bottles, “prices are up by a crazy 50%”. Lécaillon says: “It’s a safe overall guesstimate there’s been a 25% increase in all costs for now.”

At Champagne Drappier, Hugo Drappier believes that, once you add in the cost of premier and grand cru grapes, the average price is probably higher than €7/kg. However, if you want to purchase organically-certified grapes, you have to pay a considerable premium, which he puts at over 30%. “Last year organic grapes were being traded at about €11.25/kg,” Drappier says. Although Drappier now farms a large part of its own estate organically, with more in conversion, the company doesn’t buy organic grapes. Drappier sees this high price as a good thing. “We believe this will bring positive things to Champagne, as it encourages more organic viticulture, and covers better for potential loss, the higher cultivating costs, and risks involved in farming organically.

“Because our non-certified vineyards are still cultivated without herbicides and artificial fertilisers, but rather through good soil management, we get more yield variation and the cost of producing our own grapes is higher than the average in Champagne. The recent low yields [in 2020] increased our production costs [as fixed costs didn’t fall]. As a result, at Drappier, the price of grapes accounts for about 45% of our bottle costs, compared to the 36% the UMC estimates.”

Philippe Brun, who operates one of two independent presses in the grand cru village of Aÿ at Champagne Roger Brun, paid his growers €8.50/kg for their grapes in 2022, and he expects that to rise to €9 or more in 2023. He says that, for medium-sized producers, costs have risen so substantially that they have to look at making premium wines, such as single vineyard cuvées, just to stay in business.

It is a measure of the tension between supply and demand that the current sur lattes price, should you be able to find any such wines to buy, has risen to a minimum level of €10.50 a bottle of undisgorged wine. Brun says: “The impact of the low yield set in 2020 is hitting us now with huge shortages. Many producers are unable to take on new clients and, of course, prices are rocketing.

“In the past 12 months, the cost of dry materials has rocketed by over 50%, while the price of bottles has risen by 20%. We are even having to buy without knowing prices, and the lead time is much longer at around seven months, compared to just a few weeks three years ago. So I have to finance stocks of dry materials as well.”

All the environmental controls that are demanded today have massively increased the administrative burden for small producers, including Brun. He says: “Half a day for this paperwork admin was enough 20 years ago; now it takes up threequarters of my time, and I can’t spend enough hours in the vineyard or welcoming visitors any more.”

Feature findings

• While Champagne houses are facing unprecedented cost increases across the board, the price paid for grapes remains by far the biggest expense when making Champagne.

• The abolition of industry-wide pricesetting for grapes over 20 years ago has ushered in an era where the biggest player – Moët & Chandon – effectively sets the price every year.

• Thanks to the particularly small 2020 and 2021 harvests, grape prices in 2022 were the highest in history, with further premiums payable in the case of, for instance, organic or grand cru grapes.

• Larger groups should be able to weather the storm of rising costs, but smaller companies could be forced out of business – and more growers are now selling their grapes to the négoce.

• The pressure has sparked a spate of sales of Champagne houses over the past 18 months, with those that control all or part of their production the most prized assets.

Related news

Champagne Duval-Leroy passes the baton with special releases