Where are they now? Lindsay Hamilton, Farr Vintners’ golden boy

From colonial Kenya to the heart of the global fine wine trade, Lindsay Hamilton helped shape Farr Vintners into a powerhouse of disciplined buying and selling. His career charts the evolution of fine wine from passion to profession, long before it became an investment class.

Lindsay Hamilton was born on 20 November 1957 in Kenya’s Nandi Hills, then still under British rule, where his father worked as a tea planter. He spent only his first eighteen months in East Africa before returning with his mother to England, settling in Bromley near his grandparents. His father remained overseas, first in Kenya and later Ecuador, continuing his career in tea, while Lindsay grew up largely in England, maintaining close relationships with both parents despite the distance.

Wine was always part of the family fabric. Both sides had strong traditions: his grandparents kept serious cellars, and wine was discussed with near-religious seriousness. His mother recalled drinking Margaux 1928, given to her by his paternal grandfather, while on her side, the family leaned towards Burgundy. His stepfather, a BBC sound recordist, often brought wine home, teaching Lindsay early that wine could appear unexpectedly and should always be welcomed.

Formative experiences in Africa

At eleven, Lindsay returned to the Nandi Hills and Uganda during Idi Amin’s regime. The contrast between the extraordinary beauty of the landscape and the violence he witnessed was shocking, stripping away any lingering romanticism about his birthplace. The experience stayed with him. His father’s later move to Ecuador meant visits were infrequent but significant.

Lindsay’s childhood was defined by movement. He lived in Putney, spent nine unhappy months in Italy under the supervision of strict nuns, and eventually returned to England, settling first in Richmond and then in Twickenham. Stability, when it came, was hard-won. He attended Elliott Comprehensive, which offered a better education in human nature than in academics. Its social mix taught him how to deal with people from all backgrounds, a skill that would later prove invaluable. Dyslexia made conventional academic success difficult, but encouraged him to develop alternative strengths. As he later observed, becoming good at talking turned out to be far more useful than perfect spelling.

After Elliott, he went to a sixth-form college in Sheen, where dyslexia continued to make academic life a struggle. University plans fell through, despite an A in O-level history and an application to study American Studies and sociology at Hull. He was disappointed but not embittered, having already learned that progress often came through persistence rather than conventional routes.

Discovering wine at Harrods

His entry into the wine trade was almost accidental, beginning while working Saturdays in the china department at Harrods. His mother met someone who suggested he try wine instead. He began working Saturdays in the wine department before going full-time in 1975, staying until 1978. He was eighteen when he started and nineteen when he committed fully. At the time, Harrods attracted aspiring wine merchants from across the UK, including a steady stream of Oxford and Cambridge students working their holidays.

Producers regularly hosted tastings. Bollinger appeared with reassuring frequency, as did Fonseca. Long days meant staff combined breaks, allowing him to attend tastings at Sotheby’s and Christie’s. He tasted wines such as Pol Roger from the 1920s, entirely unaware that one day these bottles would be spoken of in hushed tones.

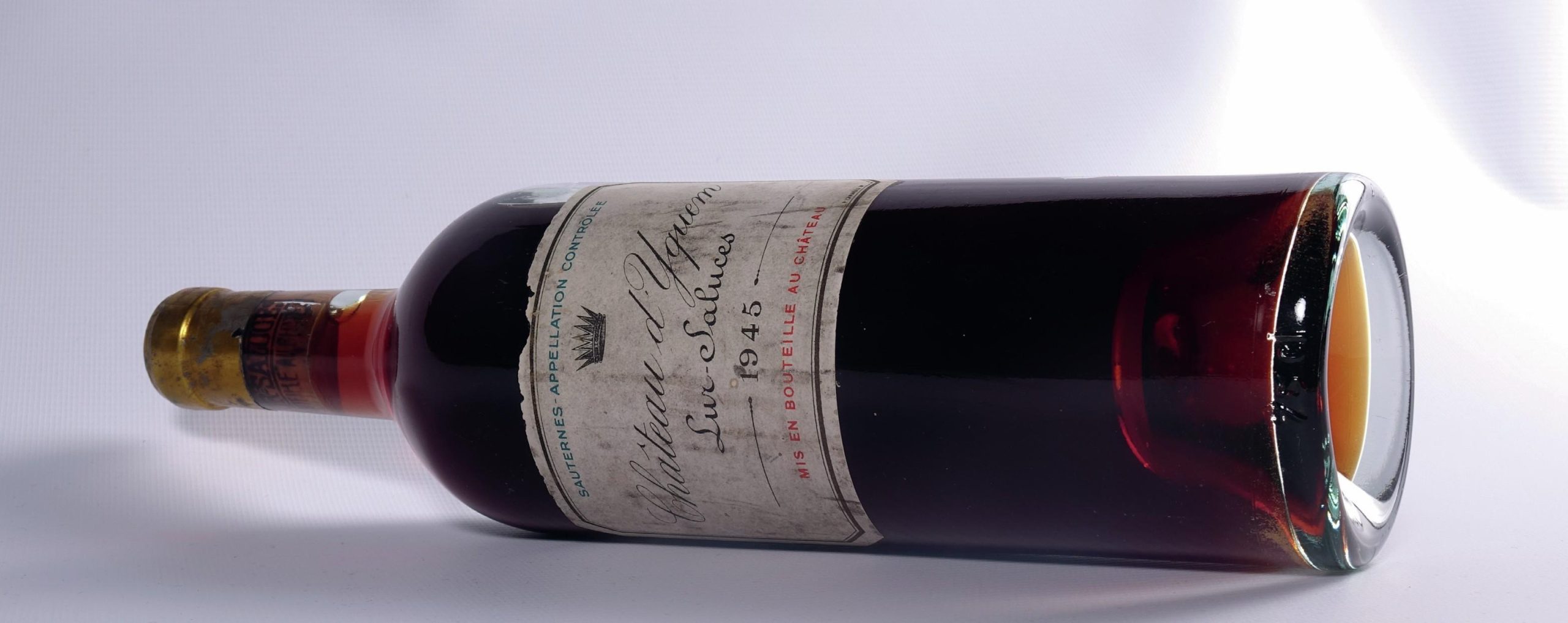

There was also a weekly wine group that met at the Cabin, next to Hedges & Butler. ‘We tasted 1945 Mouton there- twice. At £8.50 a bottle, it seemed outrageously expensive.’

These experiences lit a fuse. He was tasting extraordinary wines in improbable circumstances. Jancis Robinson attended one tasting, Oz Clarke another, and weekly gatherings continued at L’Escargot, drawing friends and customers. Through this small but intense world, he encountered auctioneers from Christie’s and Sotheby’s, including Michael Broadbent, Alan Taylor-Restell and Patrick Grubb.

The founding of Farr Vintners

Back at Harrods, he and Liam McCann began buying wine and sending it to auction. McCann wrote excellent tasting notes, says Lindsay, and through him Lindsay met Jim Farr. The three decided to start a business. Jim Farr put up £5,000, which seemed a great deal of money, and, in retrospect, admirably brave.

Farr Vintners formally began in October 1978, initially run by McCann, Farr and Hamilton. Stephen Browett would not join until 1984. McCann had the deepest experience in wine selection, and the early vision was focused almost obsessively on small-production, grand cru white Burgundy, sold primarily to California.

Partner Content

Early focus on Burgundy

Domaine Leflaive and Ramonet were central, with Ramonet proving particularly important. “These were wines of remarkable quality, long before Burgundy became something discussed in investment terms.”

They began with small growers and expanded gradually. When Guigal appeared, particularly the La Las: La Mouline, La Landonne and La Turque, it felt momentous. Their main customers were US retailers, working through importers. In the first year, turnover reached £52,000. Growth was steady rather than dramatic, but it was profitable.

Everything changed in 1984 when Stephen Browett joined and brought a serious focus on Bordeaux, a far larger and noisier market. In 1985, Browett became a partner, McCann left, and the expansion into Bordeaux began in earnest.

The approach was disciplined rather than glamorous. They dealt primarily with négociants and focused relentlessly on value. Mature vintages were bought through Christie’s and Sotheby’s when they appeared underpriced. “Many merchants treated wine as a lifestyle accessory, spending freely on cars and lunches. We preferred to retain capital.” Margins were transparent and modest, around 10%.

Fakes and hard lessons

Mistakes were inevitable. They once bought fifty cases of Cheval Blanc 1982 that later proved to be fake, purchased from a relative of a French négociant. It took seven years to recover the money, an education in patience. They also brushed up against the fake wine world of Hardy Rodenstock, complicated by the fact that Michael Broadbent trusted him implicitly.

They began buying en primeur in 1986 and in earnest in 1989, when quality, price and access aligned. Robert Parker’s influence was rising, and his endorsement of the 1989 Bordeaux vintage gave buyers confidence. “Parker delivered reliable notes and reduced reliance on merchants. He also forced châteaux to take quality more seriously.”

They did not promote wine explicitly as an investment, but understood that many customers bought more than they needed. “That dynamic is what led to wine investment,” Lindsay notes.

Building scale and modernising the business

Beyond Bordeaux, they sold selected Champagnes and Burgundies, acting as agents for Jean-Noël Gagnard, Robert Chevillon and Jean-Marie Guffens. The secondary market for DRC was important; before Corney & Barrow became agents, they bought from Percy Fox, £400 a case for Romanée-Conti. In the Rhône, Guigal dominated their buying.

Tim Doe joined in the late 1980s and helped computerise the business, a system envied across the trade. Jonathan Stevens and Tom Hudson also joined the buying team.

Leaving Farr Vintners and life after wine

By the time Lindsay left Farr Vintners in 2008, turnover had reached £78 million, with Lindsay himself responsible for more than a quarter of sales. Alongside his role as hands-on chairman, he was consistently the company’s highest salesperson. He sold his shares back to the company and left on good terms.

Afterwards, he turned to art, later worked for Bordeaux Index, and became vice-chair of O&O Cellars, later Vinum Singapore. In recent years, Lindsay and his wife have travelled widely. He still mentors occasionally in the wine trade, while enjoying a stage of life where he can relax with a great bottle without having to think about tasting notes and scores.

Related news

Where are they now? Malcolm Gluck – apostle of plonk

Where are they now? Mary Pateras of Eclectic Wines

Where are they now? Jo Ahearne MW – from Cockney roots to global winemaking trailblazer