Did Jesus turn water into wine here? New evidence emerges

Archaeologists in Galilee are unearthing evidence of the village where, according to John’s Gospel, Jesus turned water into wine – a story that continues to inspire both pilgrims and wine lovers.

If you’ve ever opened a bottle that seemed, miraculously, better than you paid for it, you’ll appreciate why the story of Jesus turning water into wine has had such a long afterlife. According to John’s Gospel, his first public “sign” took place at a wedding feast in a Galilean village called Cana. The problem is, no one is quite sure where Cana actually was.

The Israel Antiquities Authority recently published a hefty monograph by archaeologist Yardenna Alexandre. After years of digging at a mound called Karm er-Ras on the outskirts of today’s Kafr Kanna, she argues the village there was indeed Cana of Galilee. The case is built not on one dramatic discovery but on the slow accumulation of evidence: Early Roman houses, a ritual bath or mikveh, fragments of stone drinking vessels and signs of a pottery industry producing the sort of everyday jars you’d expect in a poor Jewish settlement of the time.

A 2019 excavation even uncovered a dump of pottery-production waste and what appears to be part of a kiln. This hints that Karm er-Ras may have supplied the tableware for the entire neighbourhood – rather less romantic than miraculous wine, but solid archaeology nonetheless.

The rival village up the hill

Not everyone is convinced by Kafr Kanna’s claim. For several decades, American archaeologists have been excavating at Khirbet Qana, a ruin north-west of Nazareth. Their trenches have revealed a sizeable Jewish village inhabited in the right period, complete with ritual baths, coins and even a synagogue-like hall.

Most strikingly, they uncovered a set of caves that later Christians converted into a shrine. Inside was a bench-altar fashioned from a sarcophagus lid, carved crosses, graffiti reading “Lord Jesus” in Greek and, tantalisingly, a shelf built to hold six hefty stone jars. C. Thomas McCollough, who led the digs, has argued that Byzantine pilgrims identified this as Cana and came to venerate the spot where water supposedly became wine.

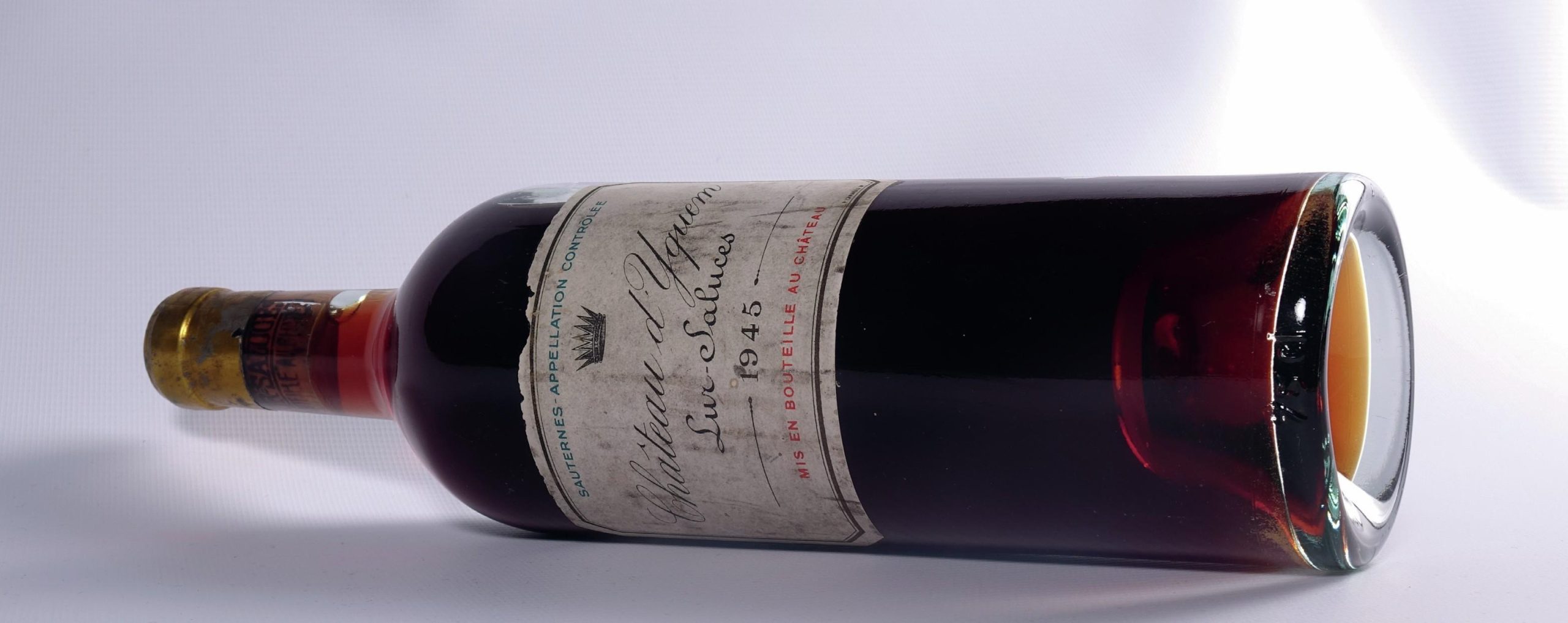

For the wine-minded, those stone jars are key. They were carved from chalk, not clay, because Jewish law associated stone with purity. At around 80 to 120 litres capacity each, they were the sort of serious containers you’d expect to find in a communal setting. John’s Gospel mentions six of them standing ready when the wedding ran dry. Even if you strip away the miracle, you’re left with a vivid image of Galilean households with their stoneware lined up like cellar bottles.

Where the jars came from

The jars themselves weren’t made in Cana at all. Recent excavations at ‘Einot Amitai, a chalk quarry outside modern Nof HaGalil, revealed the very workshop that produced them. Yitzhak Adler and Danny Mizzi’s report in Israel Exploration Journal describes how the quarrymen hewed blocks of chalk and turned them into mugs, bowls and those massive water jars. The site was active in the first century, precisely when the Cana story is set.

Partner Content

This industrial context helps explain why fragments of chalk vessels turn up in both candidate Canas. They were part of everyday Jewish domestic life, a material expression of purity as much as practicality.

Two villages, one story

So where does this leave us? Alexandre’s newly published IAA Reports 75: Cana of Galilee plants a confident flag at Karm er-Ras, aligning the excavation layers with the Gospel’s Cana. McCollough and his colleagues continue to champion Khirbet Qana, pointing to its Early Roman occupation and, crucially, the continuity of Christian memory embodied in the cave shrine.

As often in archaeology, the choice is about which set of evidence you find most persuasive. Kafr Kanna has the advantage of modern tradition – there has been a “Wedding Church” there for centuries – and now a dense IAA report to back it up. Khirbet Qana offers a dramatic cave complex and a topography that fits ancient itineraries rather neatly.

Wine, purity and a touch of levity

For those who don’t spend their weekends with a Bible in hand, what matters is this: the story is about a village wedding running out of wine, an embarrassing hitch in a culture where hospitality was paramount. Jesus is said to have instructed servants to fill six stone jars with water, which promptly turned into good wine. In wine-speak, it was the ultimate upgrade.

Even if archaeologists can never prove that moment, they are showing us the texture of Galilean life. Villages where chalk jars were carved for ritual purity, where clay pots were fired for storage and where feasts drew whole communities together. The miracle belongs to faith, but the vessels, baths and pottery belong to history – and they tell us this was a world where wine was central to both celebration and symbolism.

For wine lovers, perhaps the most satisfying conclusion is that two millennia on, we are still debating Jesus and wine in the same breath. Whether water ever became vintage on demand is a matter for faith, but the fact that Galilean soil still yields the jars, quarries and cellars of its people is a miracle enough for archaeology.