Is Romagna on the rise (without Emilia)?

Sorry Emilia – Kathleen Willcox speaks to the experts and winemakers indicating that Romagna is ready to go solo.

Peanut butter, jelly.

Tom, Jerry.

Emilia, Romagna.

There are certain things, people and places that are so closely associated with each other it is difficult to separate one from the other and understand them as individuals with their own identities, characters and flavors.

And in some ways, their partnerships make sense. The richness and salty heft of peanut butter is perfectly partnered with sweet and silly jelly. Meanwhile Tom without Jerry? Just stop.

Emilia-Romagna is one of the most beloved cultural capitals in the world. It is home to the oldest university in the world (University of Bologna), stunning Romanesque and Renaissance cities, 11 UNESCO heritage sites, ridiculously cool cars (Ferrari, Lamborghini, Maserati and Ducati are headquartered there) and some of the world’s best food (Parmigiano Reggiano, Modena balsamic vinegar, tagliatelle and tortellini were all created here).

So why would Romagna want to break up with Emilia? For winemakers, the relationship is complicated. Most people who associate any wine with the region think of cheap, fun, fizzy Lambrusco. But in Romagna, a combination of serious investments in viticulture and climate change has created the opportunity to make premium Sangiovese that is distinct from other Sangiovese producers in northern Italy.

Now, winemakers in Romagna are trying to assert their independence from both Emilia and those other much more famous regions through the Rocche di Romagna collective brand.

The Romagna DOC was founded in 2011, and the Rocche di Romagna brand and logo was officially launched in 2022 with the goal of distinguishing it from Tuscany and Montalcino, the two regions most famous around the world for producing Sangiovese.

Rocche di Romagna encompasses 16 subzones, each of which offers its own stamp on the grape, due to its distinct blend of soils, aspect and elevation.

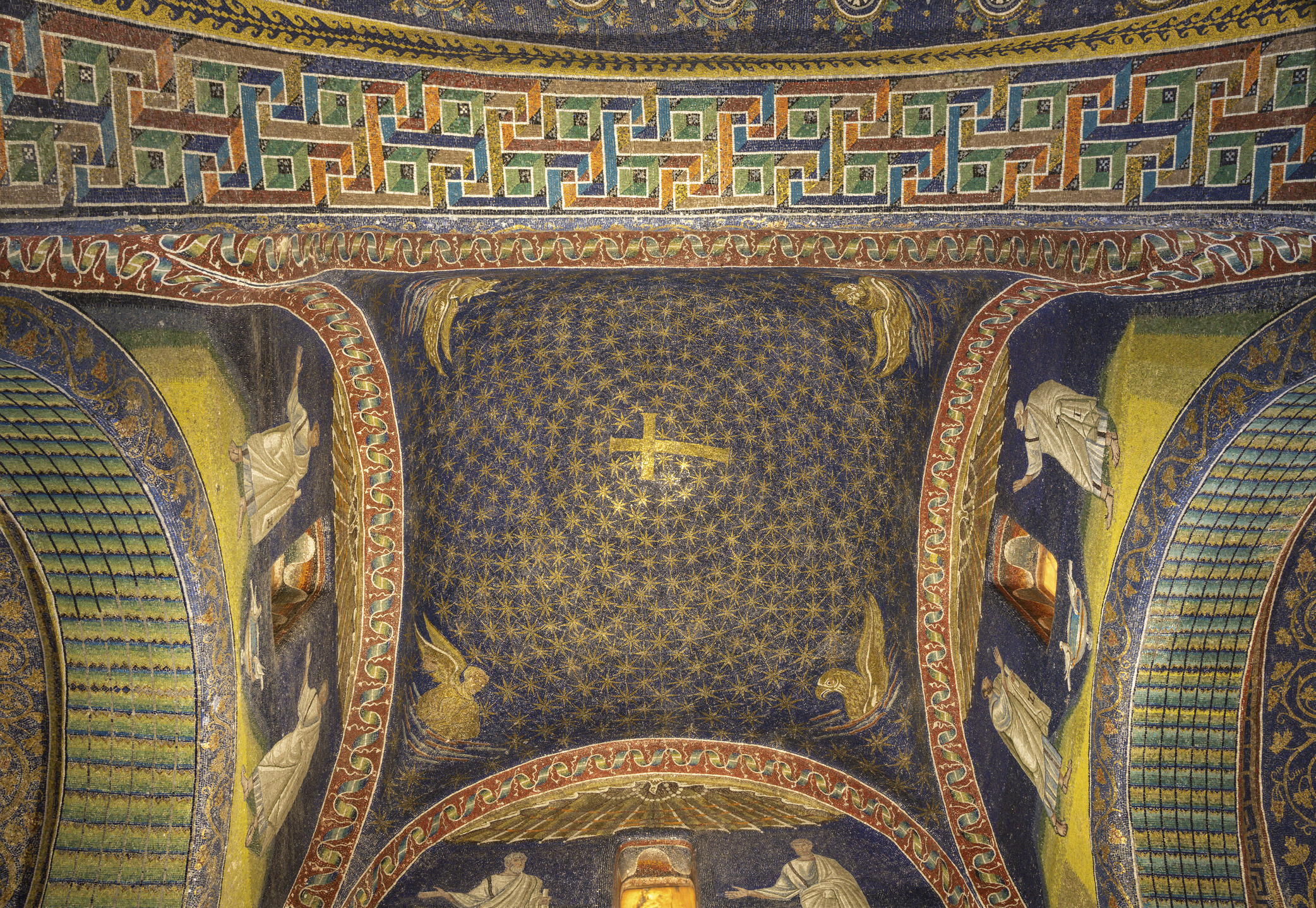

The logo is inspired by the Rocche, or castles, that distinguish the landscape, with details that echo the famous mosaics in Ravenna’s fifth-century Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, considered one of the greatest expressions of art from the Byzantine era.

Winemakers in the region are putting the logo on their bottles as a quick shorthand that, they hope, consumers will come to understand as a symbol for the quality inside (along the lines of the famous rooster of Chianti).

Romagna Sangiovese vs. Tuscany

For outsiders, the differences between the Sangiovese produced in Romagna and in Tuscany is subtle, but quite notable.

“Great Sangiovese for me is a wine that displays a deep, intensity of flavor combined with great structure and brightness, while finding a way to give a wine of sublime elegance,” says Chris Dunaway, wine director at The Little Nell in Aspen.

“Tuscany is multifaceted regarding the myriad of exposures, altitudes, and the resulting meso-climates these afford the region. For that reason, it’s best to focus on the best-known Tuscan benchmarks of Brunello di Montalcino and Chianti Classico for broader generalizations of style.”

Montalcino offers more concentration, more power and darker fruit, while Chianti Classico offers similar flavor complexity, with a focus more on red fruits and brighter acids, Dunaway explains. They are both firm and age-worthy.

“Sangiovese from Romagna often has much more approachability in youth than both, with softer tannins while being lighter in style with a more mineral, almost saltiness in the wines,” Dunaway says. “It’s said that much of this mineral character comes from the local calcareous clay soils of the area known as spungone, which is a clay-rich soil mixed with marine fossils.”

Top expressions of Tuscany will invariably command a much higher price than top expressions of Romagna, he notes.

For insiders, however, Sangiovese in Romagna is a completely different plant.

Partner Content

“In Romagna, we speak about Sangiovese Gross, which is not the Gross from Montalcino,” says Cristina Geminiani, owner and manager of Fattoria Zerbina. “They are different clones with different behavior. It’s bigger than the Sangiovese in Montalcino. We also have a soil which is richer, so the expression is more generous and the wines are a little bit easier drinking.”

While Geminiani says the Riservas from Romagna are top quality, and quite ageable, the entry level style is pure, and shows a transparent, accessible style of the grape.

Since achieving DOC status, many producers have focused on teasing out the distinct qualities of their Sangiovese, with an eye toward greater worldwide recognition.

“In the past decade, the quality of our Sangiovese has significantly improved, thanks to growing awareness of our potential,” says Giovanna Madonia’s co-owner Miranda Poppi. “Today, many young winemakers are motivated by the desire to enhance their environment, obtain organic certifications and place a great emphasis on our connection to the territory by promoting indigenous varieties and artisanal techniques.”

Serious Investment in Identity and Quality

Indeed, in a bid to distinguish themselves, producers say they are turning away from international varieties, and revisiting classic production methods. They are also going green – about 40% of the wines produced in Romagna are certified organic, according to the Consorzio.

“When I started making wine in the 1980s, the big deal was international grape varieties,” recalls Geminiani. “So I made all the possible mistakes everybody was making. I planted international varieties, white and red.” But after 15 years, she changed course, and began planting Sangiovese and Albana.

Environmentally friendly winemaking is also showing its advantages, according to Raffaella Bissoni, owner, winemaker and viticulturalist at Azienda Agricola Bissoni. “There have been significant investments in sustainable farming practices across the region, which have greatly enhanced the overall quality of our wines,” she says. “I began organic and biodynamic farming in 1988, and it greatly changes the quality of the final product because it adds the characteristics of the terroir, and a wonderful world of aromas from our wild meadows. My wines are now renowned for their distinctive aromas and high-quality profile.”

Moreover, this method of farming also protects the environment, she adds.

Others like Poppi – who says that “indigenous varieties keep our culture and identity alive, and are better adapted to local climatic conditions,” – are also revisiting ancient production methods, eschewing commercial yeast and anything but the most minimal additions of sulfites.

“We employ a strictly manual approach and intervene only when necessary,” Poppi says. “We also favour less extractive winemaking techniques and use various containers for ageing – from steel, to concrete tanks, lightly used tonneaux and barriques, while avoiding new wood – to create wines that increasingly reflect the characteristics of our territory. We also aim for long bottle maturation.”

At Tenuta Masselina, sales and marketing manager Elena Piva explains that they began exploring amphora ageing in 2010, in a nod to Romagna’s tradition of using the vessels during Roman times.

“We were among a group of Romagna producers making micro-vinifications in amphora,” Piva says. “We realized that the results were excellent because it allows micro-oxygenation. Ours are produced in Faenza, in terracotta sourced from our area.”

Climate Change Is a Question Mark

While predicting what younger and newer drinkers may connect with in the wine world often feels like a game of fantasies – in other words, a futile exercise conducted by fools – it does seem that regions like Romagna, with their indigenous grapes, interesting production methods, green values and reasonable prices would fit the bill.

But climate change, and its effects, remain an open question.

“We have a long history of growing Sangiovese here, but in the past 10 years, the quality has increased,” says Condé winemaker Chiara Condello. “Some of that is due to climate change. Reaching ripeness used to be a concern, as we are the only region north of the Appennini Mountains growing Sangiovese. We no longer have problems getting ripeness, but at the same time, we always keep a nice acidity and the beautiful freshness of the wine.”

Climate change gives, but it also taketh away. For the past two years, storms have plagued Emilia-Romagna, causing widespread property damage (including at wineries), evacuating people and even killing them. The floods of 2023 were horrific, killing 17 people and causing US$9.5 billion worth of damage. While they were less extreme this year thanks in part to structural changes implemented in reaction to 2023’s devastation, they still affected the harvest.

Every region is dealing with climate change. Few are poised to benefit from it, while also offering the style, character and flavour of wines the zeitgeist appears to be gravitating toward.

Romagna’s got it. Striding out onto center stage solo without its partner in crime may be risky, but plenty of starry solo careers have started just like that…

Related news

Cabernet Franc on track to become the official grape variety of New York State

Ridgeview Wine Estate finds new owner after administration

Fine wine defies downturn as US$250-plus bottles keep selling