Evolution solution: What does the future hold for the Loire?

From a Chenin Blanc revival to the proposal of a shared identity, the multi-faceted Loire region is undergoing real change, reports Chris Losh.

THE POSTER in the Metro station of the Gare de Montparnasse is not good for anyone about to make the 90-minute journey to the Loire on an empty stomach. Showing bottles of the region’s rosé wines alongside groaning plates of food and the tagline “Sucré, salé, rosé”, it makes you yearn for something more toothsome than a train station baguette. But the range of rosé styles on the poster also illustrates some of the Loire’s challenges.

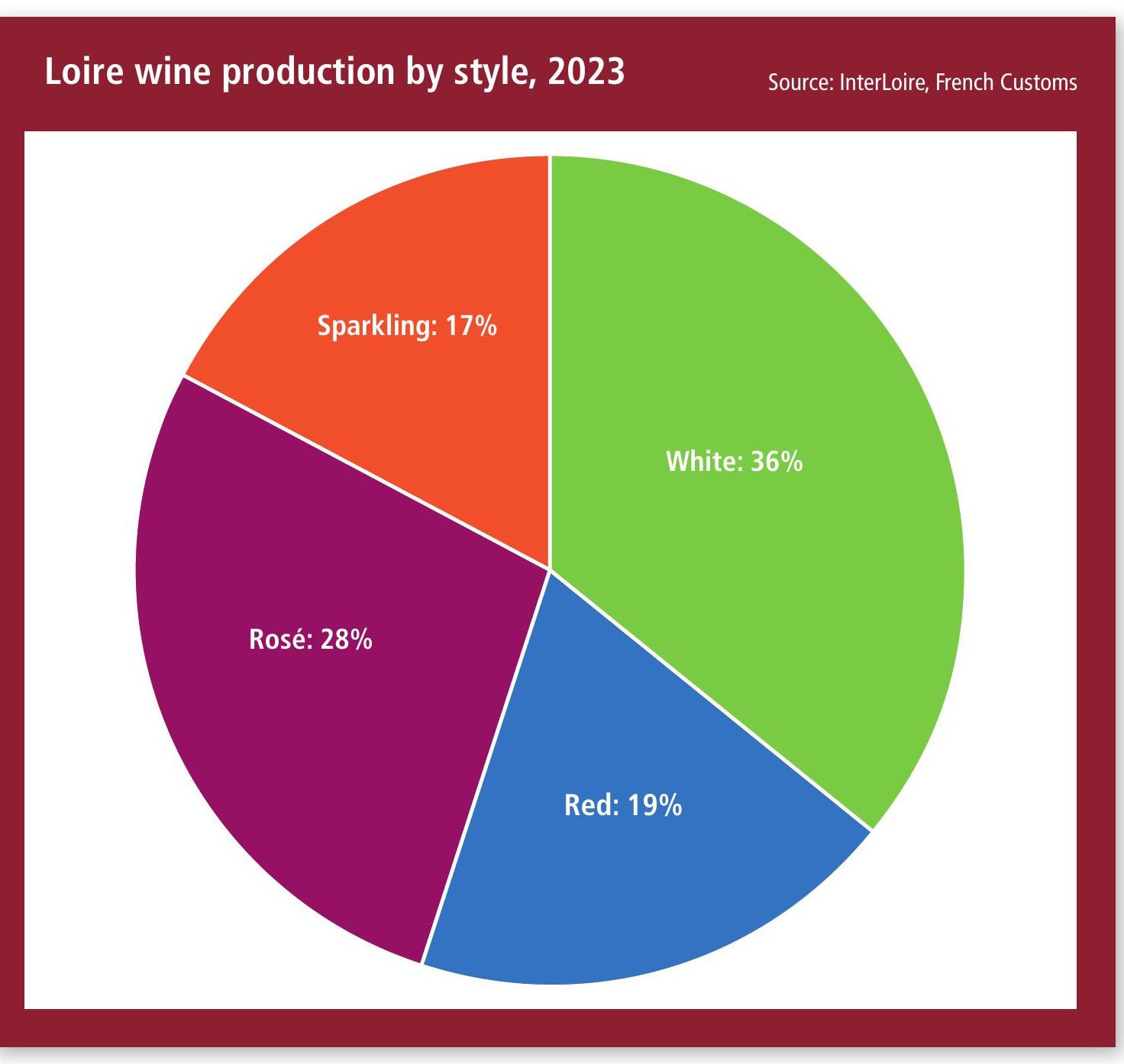

Encompassing significant volumes of everything from sweet to dry, still to sparkling, and reds, whites and rosés, the Loire’s wine output is exceptionally varied. This is a plus for engaged consumers – and a problem for anyone looking for simple answers.

Vouvray alone makes pretty much everything with one grape variety (Chenin Blanc) and not many clues on the label. One producer’s cheerful assertion to this journalist that you “need to know your producers” to ensure you’re not buying something you don’t want seems either optimistic or blasé, depending on your viewpoint.

Vouvray is one of the Loire’s superstar appellations, along with Sancerre, Pouilly-Fumé and, to a lesser extent, Chinon and Muscadet. These are wine styles with global resonance and recognition although, somewhat ironically, it’s debatable how much good they do the wider Loire region.

“In the US, Sancerre is a brand,” says Lionel Gosseaume of Domaine de Pierre, who is a former president of InterLoire. “But, even in France, 50% of Parisian consumers don’t know it’s from the Loire.”

Problem of scale

The problem, perhaps, is one of scale. It’s around 400km from the westernmost vineyards of Muscadet to Sancerre in the east, and a further 200km south from there to the Côte Roannaise, and another 100km to Côtes du Forez.

These inland, continental vineyards are a world away from the salty dampness of the Atlantic coast; AOPs with little in common other than a proximity to the somewhat morose meanderings of the Loire river itself.

However, the locals do see some similarities. “We don’t have a lot of négociants or co-ops,” says one vigneron. “We’re a region full of family-owned wine growers, who get their arse on a tractor and are involved every day.”

Others cite the fact that more than half of the wine estates are committed to environmental certification or organic farming. “We aren’t as famous as Bordeaux and Burgundy, so we need to do something different,” says Michel Bodet, at Domaine Yannick Amirault in Bourgeuil. “The natural way of processing [grapes] is important to us.”

Finding a USP and gaining consumer recognition have arguably never been more important, because the domestic market – an absolute staple of Loire producers since the days when they were bistro wine supplier of choice to the French capital – is in steady decline.

“Fifty years ago, [wine consumption] was one litre per person per day in France,” muses Anatole de la Brosse of Domaine des Closiers in SaumurChampigny. “It’s very different now.”

Research group Statista shows that wine consumption in France has fallen from 70 litres per capita at the turn of the millennium to the mid-40s now. Others think it’s far lower even than this. But what isn’t in debate is the downward trend. As in many mature markets, there are two key drivers in France: ‘less but better’, and the move away from red wines towards whites and sparkling. Consumption of Loire reds in France has dropped by 35% since 2010, with cheaper wines bearing the brunt.

“Even in Saumur-Champigny, there are people who make cheap wine, and they have found it hard,” says de la Brosse. “People don’t want to drink that [level] any more – and, of course, we are still cheaper than Bordeaux or Burgundy.” In all-white Vouvray, producers have found the going easier than in red appellations, but even here there have been changes.

“We have the same number of customers, but they drink less, and now they want a premium cuvée,” says Guillaume Paris of Domaine Paris Père et Fils. “Twenty years ago, we didn’t need to export to sell our production; now it’s essential.”

Common theme

This increased emphasis on exports is a theme that is repeated across the region, and it’s a big focus for the InterLoire generic body, which is hoping to increase the proportion of its members’ bottles sold abroad from the current level of 21% to 30% of sales by 2030.

With its wide diversity of wine styles, myriad appellations and a large number of pretty small producers, gaining greater recognition for the wider Loire region is central to any expansion, says InterLoire’s president, Sophie Talbot.

She is encouraging producers from all appellations to brand themselves as Vins de Loire to achieve it; to use the overarching pan-regional descriptor, as well as any appellation descriptors. “We don’t want to erase the personalities of our AOPs or PGIs,” she says. “But we want everyone to see they can be part of a common identity.”

This seems sensible, although it will rely on significant buy-in from a large number of growers to be successful, and will need to be maintained over a prolonged period to gain resonance with consumers who can’t pronounce Loire, never mind find the region on a map.

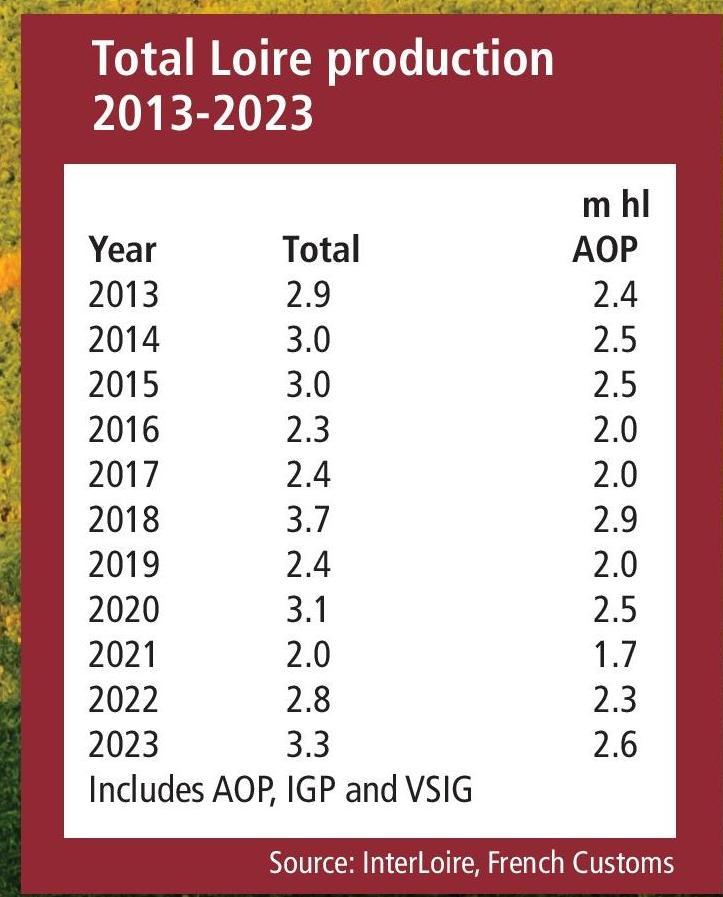

A further factor making a prolonged assault on export markets difficult is – frustratingly – out of the hands of the region’s producers: vintage variability. The Loire’s cool northerly location means that its wines have generally weathered global warming pretty well (of which more later) – at least when it comes to style. However, vintage sizes are another story. Warm winters and early vine activity have left plants exceptionally vulnerable to spring frosts, while summer hail and mildew caused by higher humidity have taken their toll too. The table on the facing page shows this with demoralising clarity.

There have been only two vintages since 2013 that are notably larger than average. Four vintages, on the other hand – 2016, 2017, 2019 and 2021 – have been very much lower than the norm.

“We are more and more sensitive to frost,” says Gilles Colinet, owner of Château de Berrye. “It’s about every three or four years. In 2021, we lost half our harvest.”

At Château de Valmer in Vouvray, the description of recent vintages offered by Jean de Saint Venant is a litany of woe. He explains: “[After] 2019, it was Covid, so we only sold half our production; 2020 was dry, so we were down 20%; 2021 was a disaster; 2022 was dry, so down again; and then, in 2023, there was a lot of volume, but quality was a problem.”

De Saint Venant reckons he has lost the equivalent of one year’s-worth of production since 2019, and two years’- worth since 2010.

Making up for that kind of lost income is tough – particularly for a region where bottle prices are affordable, rather than expensive. At UK Loire specialist Yapp Brothers, CEO Tom Ashworth says he has “definitely seen more people selling up or giving up than in other regions”. For instance, one of Yapp’s favourite Muscadet producers recently sold his vineyards and became a landscape gardener.

The plus side, perhaps, is that land prices here remain relatively affordable. At €10,000–€15,000/hectare, it’s possible for new or young hopefuls to gain a foothold in good regions with mature vines. Nicolas Gonnin, a young organic, natural wine producer with the 5ha Vignoble du Rab, is perhaps typical – and he’s optimistic.

“We’re suffering [with volumes] at the moment,” he says, “but in general we are less affected by climate change than in Bordeaux or further south.”

This is a good point. Growers in StNicolas-de-Bourgeuil have teamed up to blanket their vineyards with more than 100 frost fans – a huge investment, but one which has largely safeguarded volumes. And, once volume fluctuations are minimised, they are happy with what they are seeing.

The Loire’s temperatures now are similar to those of Bordeaux in the 1960s – and this has been good news for the fruit profile of the region’s Cabernet Francs. “Those green notes are a thing of the past,” says Louis Germain of Domaine des Roches Neuves in SaumurChampigny. “I’m 100% sure Cabernet Franc is a grape for the future – it’s a way to bring back freshness.”

Signature red

The impact of climate change is such that many winemakers now think the Loire’s signature red variety actually performs better in cooler years than warmer ones, when the fruit is brighter and the tannins usually better-mannered.

Higher summer temperatures are leading to a growing interest in Côt (Malbec) too. AOP Touraine is increasing the minimum amount of the grape required in its reds from 25% to 50% by 2030. AOP Touraine Amboise reds have had to be 100% Côt since 2019.

Not that it’s as simple as ‘warmer equals better’ for red varieties. Etienne Neethling, professor in viticulture and oenology at the Ecole Supérieure des Agricultures in Angers says that making red wines in elevated temperatures is actually more challenging than whites, with sugar ripeness often running way ahead of phenolic ripeness, and growers forced, as a result, to choose between high alcohol or unripe tannins.

Sauvignon Blanc growers, too, are finding life awkward, with the Loire’s trademark grassy notes being superseded by more tropical flavours. Trimming back vine canopy to reduce ripening is helping for the moment but, as Lionel Gosseaume admits: “That might not be enough in 25 years’ time.”

As a result, we can expect to see forgotten, high-acid old varieties such as Orbois (Arbois) and MeslierSaint-François (currently under experimentation) making a return in some shape or form in the coming years. Given all the above, the big winner of the last 20 years in the Loire is clear. Chenin Blanc is on a roll. Its naturally high acidity is allowing it to navigate higher temperatures without losing structure – any grape that can survive the sun in Stellenbosch isn’t going to struggle too much with a degree more of heat in Saumur – and its ability to make still whites and sparkling give it real flexibility. It helps, too, that white wine and fizz are on consumers’ wish list.

“There’s a huge demand for Chenin Blanc,” says Clotilde Legrand of the eponymous Domaine Clotilde Legrand.

“For white wine in general, but for Chenin Blanc in particular. It can produce very good wine in any soils. Different, but still good.”

It’s a point that has been made before by Ken Forrester in South Africa: that the variety is “just at home barefoot as it is in high heels”. Interestingly, Loire producers are quite open about how the work done by the Cape’s wineries with the variety has helped to revive their own fortunes. In terms of total plantings, Chenin is very close to Sauvignon in the Loire, and it’s growing, with some of the more optimistic Cabernet Franc vineyards, in particular, slowly being replaced. Saumur growers point out that their appellation was almost entirely white until the global demand for red wines in the 1980s saw wholesale Cabernet Franc plantings.

Photo courtesy: ©InterLoire

“It’s possible that Chenin Blanc could overtake Sauvignon Blanc, which has big problems with global warming,” says Guillaume Paris. “With Chenin, even if we harvest late, we keep the freshness.”

Perhaps the best indication of Chenin’s revival is that growers in Saumur have bestowed their ultimate accolade on it: creating six Dénominations Géographiques Complémentaires (DGCs) – effectively crus in waiting – for the still wines. Whether or not the world needs more layers of classification is, perhaps, a moot point. But their creation certainly illustrates the direction of travel and, growers say, will help them to charge more for their best wines.

And here, there is consensus. If there’s one thing that the Loire has across the board, it’s value for money.

“On a qualitative basis, the top Chenins are on a par with good Burgundy,” says Yapp Brothers’ Tom Ashworth. “You can still be drinking really good Savennières with some bottle age in a restaurant for £50–£60, which you can’t with Burgundy. Prices have gone up – sometimes by 30%. But it’s still difficult to pay more than €10 for Loire wines from an export point of view. Burgundy starts at that level whereas, with the exception of a few star names, hardly anything in the Loire is over that. “It’s still fantastic value – and hugely underrated.”

Related news

Timeless elegance: Crémant de Loire’s leading light