How climate change has made Champagne like Châteauneuf-du-Pape

Ruinart chef de cave Frédéric Panaïotis told db earlier this month that a changing climate has given Champagne similar conditions to those of southern France 40 years ago, as he launched Ruinart’s first new cuvée in over 20 years.

Ahead of the release of a distinctive and delicious pure Chardonnay expression from Maison Ruinart called Blanc Singulier – which you can read more about here – Panaïotis went through a presentation on the changes in Champagne featuring a wide-ranging set of climate and viticulture data going back to the 60s.

Having shown various charts, he said that conditions in a vintage such as 2018 – the hottest on record – “were more like Châteauneuf-du-Pape in the 80s, than Champagne.”

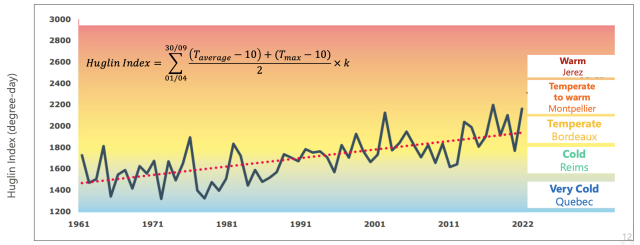

Drawing attention to a graph showing the Huglin Index in Champagne from 1961 to 2022 (below), he said that the appellation had shifted from being classified as a “cool climate to a temperate one”, although in certain vintages, such as 2003, ’18, ’20, and ’22, it would be classified as a “warm” region, like Montpelier, he said.

Indeed, 2018 “broke every single record” in Champagne, and scored 2,200 on the Huglin Index – a figure you would find, for instance, in the Port-producing region of the Douro today.

The Huglin Index is essentially a measure of growing degree days, which are those when the average temperature exceeds 10 degrees Celsius, and is used to classify viticultural regions from “very cold” – such as Quebec – to “warm”, like Jerez.

Speaking of the change that has taken place in terms of the climate in Champagne this century, he said that “the warmest years of the past, such as 1964 and ’76, are the norm of today”, adding that the three hottest vintages (’18, ’22, 03), “did not exist in the past”.

“Some might compare 2018 with ’59 or ’47, but this is not the case, it is not the same, we have entered a new era,” he said, referring to the hottest vintage in Champagne compared to legendary warm years of the past century.

While the message sounded alarmist, Panaïotis said that a warming climate in Champagne had so far been good for the region. Again, looking back, he said that years such as 1965, ’72 and ’77 were terrible, commenting, “we could barely make wine”, before noting, “those years don’t exist anymore, which is good, we don’t have to deal anymore with completely unripe grapes.”

Indeed, he showed how the average temperature in Champagne had gone up by 1.3 degrees Celsius comparing the period from 1991-2020 with 1961-1990, remarking, “It is not actually that much, and it helps to ripen the grapes”.

He also had “good news about rainfall”, which he said, “has been stable since the 60s”, when considering average annual totals, adding, “So we don’t suffer yet in our region from water shortages, even if we see more rain in winter and drier periods, even droughts in summer.”

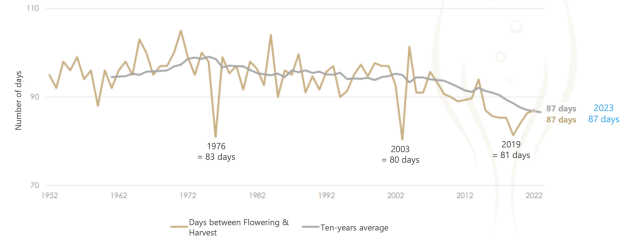

However, an area of change that is less positive for Champagne concerns a shortening of the growing season, mainly due to warmer, sunnier and drier summers accelerating the grape ripening process, but also due to an earlier start to the season, which, he stressed, was not due to an earlier bud-break, but an earlier flowering of the vines.

“An early flowering combined with warmer summers ended up with our first harvest in August, which was in 2003,” recorded Panaïotis.

Continuing, he said, “We’ve now had seven harvests in August,” which means that picking the grapes in this month was becoming “the norm” in Champagne, when late September was common for a start-date in the 60s, 70s and 80s. In more recent history, 2013 was an exception, as it was a late harvest, which he said “was mainly due to a late flowering”.

He then pointed out that the number of days between flowering and harvest “used to be 98-99 days, but now it is 87 days”. In years such as 2003 or 2019, it was 80 and 81 days respectively, meaning that “the cycle is considerably shorter,” commenting that “80 days is too short to have fully ripe grapes taking into account physiological maturity.”

Partner Content

More generally, he said that a shorter cycle means “losing potential complexity”.

As for frost-risk in Champagne, he said that the region did not appear to have become more prone to damage from freezing conditions at the earliest stages of the growing season.

“Contrary to what we say, we can’t say that milder winters translate into an earlier bud break – so far it’s not the case,” he stated. While the region is still prone to spring frost damage – with Champagne for example, “seeing 3% of the area damaged by frost this year – it’s not like we are seeing bud break in mid-March,” he added.

Nevertheless, as noted above, “If we look at the flowering period, it is a clear indication that springs have been warmer – from the late 80s we have lost about two weeks: we are now flowering two weeks earlier than what we used to,” he stated.

Finally, speaking about current conditions in Champagne, which have been unusually wet, he said, “The weather has been pretty challenging over the past three weeks – it is a good year for trees and hedges but bit more challenging for vineyards and grapes.”

As reported by db earlier this month, 2024 has so far been “an exceptionally rainy growing season”, with the Comité Champagne noting that the “entire vineyard” has “suffered from strong but controlled mildew pressure”.

Furthermore, spring frosts and hail had have “a moderate impact on harvest potential (around 10%)”, it said, while “vine development is 5 to 6 days behind the ten-year average”, with harvesting “scheduled to start around September”.

Such have been the challenges so far this year for growers in Champagne, at a press launch for Dom Pérignon 2015 earlier this month in London, attendees were told by the prestige cuvée’s cellar master, Vincent Chaperon, that yields could naturally be as low as 8,000kg/ha.

Nevertheless, Chaperon is hopeful that a low-yielding vintage could be a good one in terms of quality.

“If the sun starts shining it could be a very qualitative year, because a moderated yield in Champagne is for the best,” he said, before noting that “the bunches are quite loose, which is good for circulation, and so good for maturation.”

Read more

Ruinart releases first new cuvée in 20 years

Champagne limits yields to below 290m bottles for 2024

Dom Pérignon 2013 ‘last of the Mohicans’, says cellar master

Related news

Non-vintage is ‘putting together a puzzle’ says Champagne Lallier