Strong hold: Is Burgundy still the global benchmark for Pinot Noir?

Burgundy has led the way for Pinot Noir for decades – but the French region faces a series of challenges, which are allowing rival origins to gain ground with the grape, warns Chris Losh.

THERE’S NO question what the grape variety of the 21st century has been. If the 1980s and 1990s were about uber-concentrated reds that absorbed daylight like a black hole and could be speared with a fork, the last 20 years have seen a shift to altogether lighter and more delicate wine styles.

Pinot Noir is very much the posterchild of this new movement. Admittedly, it’s been helped in no small part by the 2004 film Sideways, which did a number on Merlot so brutally destructive that it’s a wonder it hasn’t been investigated by the police.

But still, the numbers don’t lie. Plantings of Pinot in California have increased sixfold (to 18,000 hectares) over the last 20 years; in Oregon they are up by a factor of five (to 10,000ha). Even in long-established Burgundy (where Pinot is 40% of the total), hectarage has gone up by more than 20% since the millennium.

So it’s a grape on a roll. But the influx of positive energy has given this part of the wine world a slightly crazy feel; a turbulent confluence where artistry, tradition and uber-terroir crash headlong into sky-high prices, empty cellars and vaulting ambition.

This seems fitting. Contradiction and paradox are as much a part of Pinot Noir ’s leitmotif as thin skin and red fruit. I’ve lost track of the number of times that ‘New World’ winemakers have assured me they are absolutely not trying to make red Burgundy, yet are visibly delighted if you describe their creation as “quite Burgundian in style”. Or of the sommeliers who will praise a non-French Pinot to the rafters for being balanced, complex, varietally expressive and great value – only to add regretfully: “But, of course, it’s not Burgundy.”

Like it or not, Burgundy still sets the tempo for Pinot. The starting-point for every benchmarking, the region’s gravitational pull seems inescapable. That said, a recent trade tasting in London saw dozens of Burgundy growers hopefully looking for importers. Two years of having no wine to sell had left many short of both cash and contacts. In the French market, wine consumption has been falling for decades.

And, while the trend to buy ‘less but better ’ might be affecting the Pays d’Oc more than the Côte de Nuits, the move away from alcohol generally is hitting everyone.

As, too, is climate change. A couple of years ago, an online tasting with a Burgundy négociant presented five vintages, describing four of them as being from an “unusually warm year”, which rather suggested that sun and higher temperatures were not so much “unusual” as increasingly the norm.

This isn’t, it must be said, entirely bad. “Warmer vintages help with consistency,” says Christophe Deola, domaine director at Louis Latour. “We have more often the ripeness and balance achieved in legendary years like 1929 or 1947.”

MORE APPROACHABLE

The Burgundy wines might lack some of the nerviness of old, but they are significantly more approachable when young.

“High heat over a couple of weeks doesn’t change the character of the fruit so much as the structure,” explains Grégoire Bichot of Domaine des Clos, which has vines in Beaune, Nuits-Saint-Georges and Chablis.

“Especially during the last five years, we’ve seen more body and suppleness, and less aromatics.”

Does this mean Burgundy’s wines are becoming more ‘New World’ in style? Bichot turns the colour of Chablis.

“The difference is the acidity,” he says. “They don’t have that. Even in 2020, which is a ripe vintage, there is acidity…”

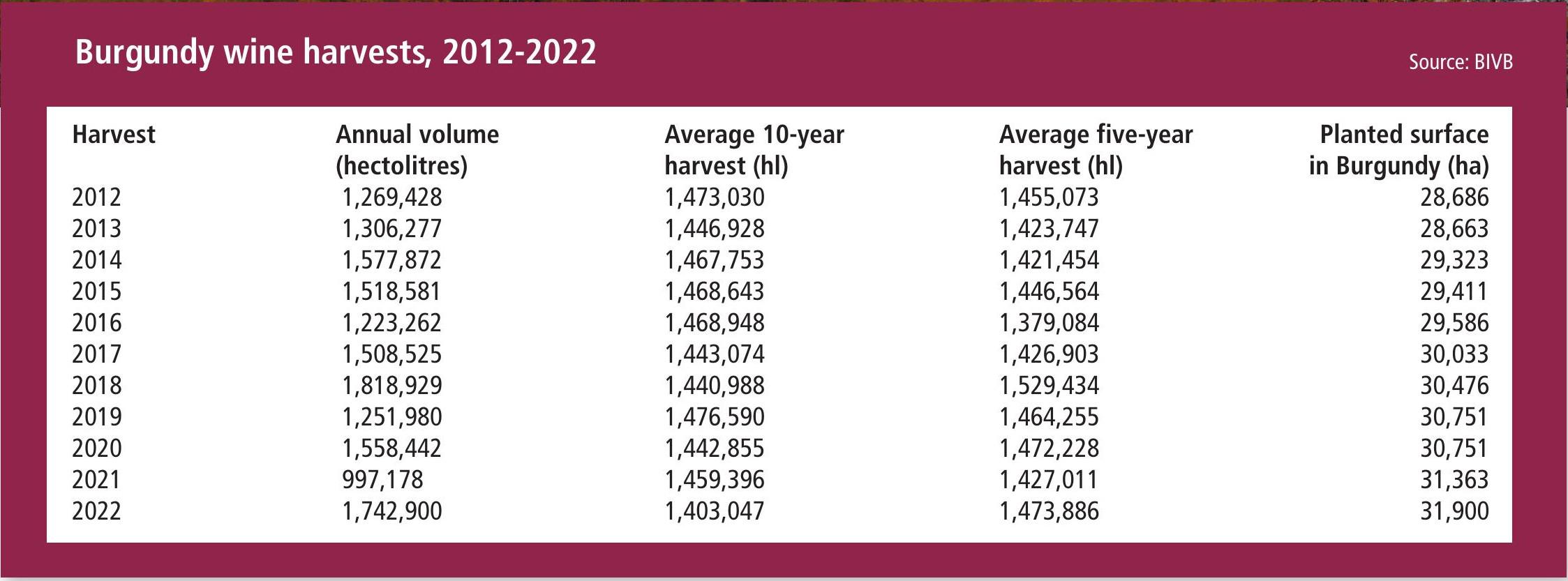

Oddly, while climate change has had less of an effect stylistically on such an ultra-expressive variety as Pinot Noir than you might think, it’s had a big impact on volumes. One grower told me that Burgundy’s vineyards have been hit by hail in 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2023, and by frost in 2016 and 2021, while 2015 was unusually hot. In other words, not many ‘normal’ years over the last decade.

Go back 20 years, and the amount of wine made during an average vintage in Burgundy was around 1.5m hectolitres. In 2022, the 10-year average fell to 1.4m hl – amounting to 130m fewer bottles of wine over the decade.

The situation has been exacerbated by the events of 2021. Decimated as it was by the spring frost, it ended up being the smallest vintage for 70 years.

“We have lost the equivalent of one vintage over the three years between 2019-21, and the equivalent of three vintages in the last 10 years,” says Nicolas Dewe from the Bourgogne de Vigne en Verre group of producers.

As James Simpson MW, of Drouhin’s UK importer, Pol Roger, puts it: “Hail used to be all but unknown in Burgundy 40 years ago. Now they’re trying to find 57 ways of avoiding it because it can crash a vineyard in five minutes.”

Rather like riper fruit, the region’s growers are resigned to vintage fluctuations being the new normal. But Burgundy is a relatively small producing region, and it makes a wine style that is heavily in vogue. Shortages have an immediate impact on pricing – particularly when they occur regularly.

“A price increase of 20% is a lot,” admits Dewe. “But in many cases it still wasn’t enough to cover the loss of production.” Many growers, he says, have had to take out short-term loans to ease cash flow problems. That’s a tough call with interest rates at 5%.

TO THE RESCUE: 2022

Thank goodness, then, for 2022. At 1.7m hl, it’s the second-biggest Burgundy vintage in the last 20 years, and seems to have been generally well-received by the trade. Although, frankly, given how desperate the wine world is for red Burgundy after 2021’s feeble showing, it would need to be borderline undrinkable to receive any push-back.

To ease allocations, the 2022s have mostly been released slightly earlier than usual. But the key to the region’s health could be the 2023s. At an estimated 1.9m hl, it’s the biggest vintage for a long time and should, finally, give producers something to sell going forward.

That said, perhaps the key question is not how much is now available, but what impact, if any, these volumes will have on pricing. Leaving aside the silly-money grands crus, there’s a big gap between what cash-strapped producers feel they need to charge, and what the markets will tolerate.

Kate Hewitt, senior communications executive at fine wine marketplace Liv-ex, says Burgundy’s trade share has dropped from 31% in 2022 to 24% in 2023. “When one can buy a Bordeaux second growth for the same price as a Burgundian village wine, one might start to question the region’s market dynamics,” she muses. Paddy Shave, head of wine sales at Brightwells Auctioneers, agrees with this assessment. “You only need to look at the almost daily trade offers on top-end Burgundy to realise that things aren’t what they used to be,” he says.

At a time of financial uncertainty, investors are tending to sell rather than buy. And, when they do either of these things, it seems it’s mostly with Bordeaux, not Burgundy.

All parties are hoping that prices will come back down for the 2023s, but the optimism is tentative and few would be surprised if it didn’t happen. Meanwhile, Burgundy is in danger of pricing itself out of the market, particularly at the ‘drinking’ rather than ‘investing’ end.

Hal Wilson, of award-winning UK independent retailer Cambridge Wine Merchants, says that almost 80% of the Pinot Noir the company sells comes from somewhere other than Burgundy.

“If Burgundy led the way in introducing people to Pinot Noir,” he says, “it is now in danger of losing it.”

This, then, looks like a big opportunity for the ‘New World’s’ Pinot producers: a wine style in demand and their main competitor becoming increasingly unaffordable. Moreover, a growing number of producers outside France are finding a sweet spot stylistically with the grape.

The early expressions of Pinot in the ‘New World’ were often somewhat clunky, with too much fruit and oak. But many winemakers now have first-hand experience of working in Burgundy, and have come back from the region armed with techniques that they are happy to use – and adapt – to get the best out of their regions.

“I think the best producers aren’t necessarily stuck in Burgundy’s orbit as such,” says Freddie Bulmer, Australia/New Zealand buyer for retailer The Wine Society. “It’s important [for them] to reflect the terroir of their region, rather than to try to manipulate something to taste French.”

If ‘New World’ Pinot producers used to claim stylistic independence from Burgundy while jealously trying (and failing) to imitate it, this thinking has changed to something that is now increasingly nuanced.

“I wouldn’t refer to Burgundy as a template,” says Jen Parr, an Oregonian now making wine in New Zealand’s Central Otago for Valli Vineyards. “Perhaps it’s more of a reference point. Understanding our own conditions, soils and climates isn’t an act of imitation, but rather one of humility.”

This combination of appreciation for Burgundy with an honest appraisal of its strengths and weaknesses – and how they compare to one’s own region – is echoed by Kumeu River Wines’ head winemaker Michael Brajkovich MW.

He admits that fine red Burgundy is the “benchmark by which all Pinot Noir is judged”, but also points out that “there are many other sources of Pinot Noir around the world that are better than many of the wines from Burgundy”.

This is particularly true at the £20–£40 level, where Burgundy’s lower end is now competing with some pretty high-quality offerings from the ‘New World’. Being stylistically similar – but better-quality and the same price – as Bourgogne rouge is causing buyers to rethink their earlier prejudices.

“Even when they loved Oregon wines, some export markets wanted them to be cheap,” says David Millman, president and CEO of Domaine Drouhin Oregon. “But steadily, people have come to accept that we’re charging very fair prices for the quality. Our value in the whole wine market (not just versus Burgundy) is being recognised.”

SERIOUS CONTENDER

Oregon’s history with Pinot Noir is lengthy – the first plantings went in during 1965 – and the US region is increasingly being seen as a serious contender, not least by the myriad Burgundian winemakers who have decamped there to explore the area’s increasing potential.

Frustratingly, Oregon’s progress is also being held back by climate change. Wildfires have become a major annoyance. Smoke taint heavily reduced the 2020 vintage and has hampered the region’s ability to cash in on Burgundy’s own volume shortfall.

Talk to sommeliers around the world and you see all of these trends mirrored on wine lists.

Top Burgundy is eye-wateringly expensive, but a sellable must-stock in the right venues. And, while price-sensitive customers might initially ‘trade down’ by dropping down the ladder of their favourite growers from grand to premier cru and even village wines, ‘New World’ regions – particularly Santa Barbara, Central Otago and Oregon – are increasingly viable alternatives to cheaper expressions.

Indeed, Ashish Jha, who works at five-star restaurants in Queenstown (New Zealand) and Dubai, says his customers are equally as interested in these regions as they ever are in Burgundy. But, interestingly, this isn’t simply a story of ‘Burgundy being attacked by the New World’. The hegemony of Pinot Noir itself is under threat.

“Nowadays, we as sommeliers are looking beyond Pinot,” says Andres Ituarte, head sommelier at Mandarin Oriental Mayfair in London. “There are so many amazing wines made from the likes of Nebbiolo, Gamay, Nerello Mascalese, Grenache, Trousseau (the list goes on…) that can offer something similar but at a better price point.”

Value is particularly important when you add in restaurant margins. Only a small percentage of consumers are prepared to pay £100-plus for a bottle on a wine list. Burgundy, for sure, and Pinot to a lesser extent, barely operate in the sweet spot of most restaurants or retailers.

So Pinot has its challenges. Stylistically, it’s broadly in a good place, with more consistency, and the extremes of underand over-ripe wines increasingly rare. And it’s still massively in demand.

The problem is availability, with growers increasingly resigned to seeing vintages trashed by extreme weather. This leads to higher prices and – eventually – to listings being lost to cheaper regions or grape varieties. The key is to be able to bank enough money in the good years to see out the inevitable troughs.

As Nicolas Dewe from Bourgognes de Vigne en Verre puts it: “Recently, people didn’t push Bourgogne [Burgundy] wines too much. But we have comfortable availability for the next few years now. So let’s get to work again!”

Who knows? With a third good harvest in a row, we might even soon be talking about a surplus… db

Related news

Garcés Silva: fresh thinking from Leyda

Christie's to sell Burgundies from renowned British collector Ian Mill KC