Front row seats: The remarkable rise of Virginia wines

Judging by its growing number of high-end wineries, Virginia is to the east coast of the US what California is to the west coast. And this promising wine region is about to come of age, reports Roger Morris

FOR AN emerging wine region to be commercially successful, it needs to accomplish three basic things – have the terroir to grow quality grapes, attract the talent and infrastructure necessary to convert these grapes into quality wines, and then possess the marketing expertise to convince enough people to continually purchase the wines. Globally, dozens of regions have reached this plateau.

But for a wine region to be recognised as world-class, one whose best wines can command premium prices and be sought out by collectors, it must hurdle a higher bar – establish a universal reputation that the wine elite can no longer ignore. On America’s east coast, those who make wine in the state of Virginia, and those in the wine trade who closely follow them, believe the region is now primed and ready for its star turn.

Much is made of America’s third President, Virginia’s Thomas Jefferson, who in his younger years toured France on a wine-buying spree and later vainly attempted to establish a successful vinifera vineyard at his plantation, Monticello, in the early 1800s. In spite of this engaging back-story, Virginia’s commercial winegrowing industry didn’t seriously begin until the 1970s, less than 50 years ago. As late as 1980, it had only six producing wineries.

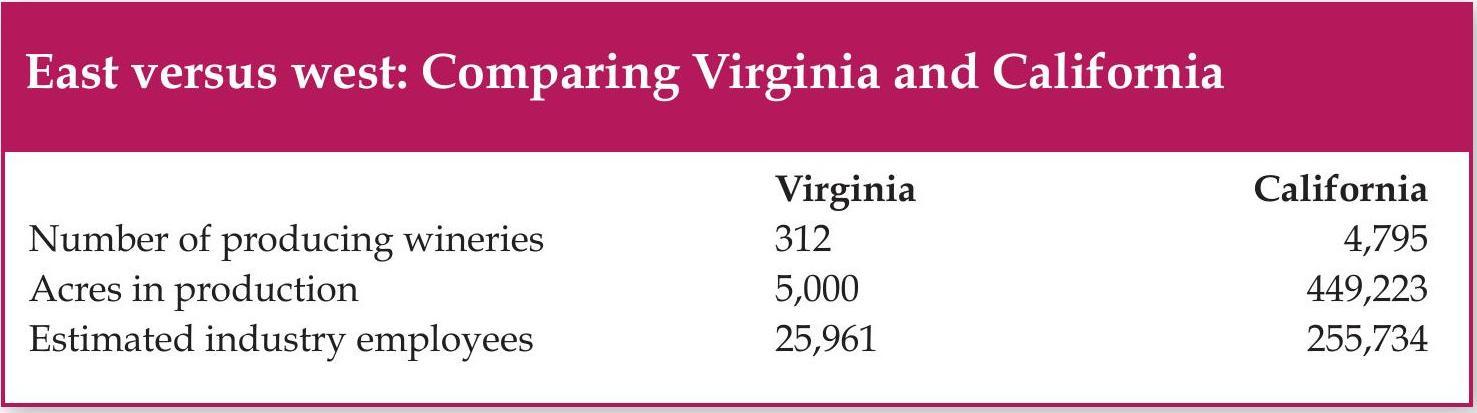

Since the turn of this century, Virginia has been racing to catch up in numbers and quality with its west coast cousins. Today, there are about 312 producers in the state, according to the Virginia Wine Board, and dozens of independent grape growers collectively farming more than 5,000 acres (2,000 hectares) of vineyards.

“The biggest asset for winemaking in Virginia is that there are no restrictions – you can do what you want,” says Michael Shaps, who makes wines in both Virginia and Burgundy.

Rich variety: Virginia’s vineyards are highly geographically diverseThere is also a healthy mix of winery profiles. First, there are the quality pioneers, such as Gabriele Rausse and Luca Paschina, both at Zonin-owned Barboursville Vineyards (founded in 1976), not to mention Jim Law at Linden Vineyards (1983) and the Horton family of Horton Vineyards (1989), all of whom shared their expertise with newcomers.

More recently, well-financed, business-experienced investors have created California-style showplace wineries with sophisticated wines to match. These include Boxwood Estate Winery, Early Mountain Vineyards, Kluge Estate Winery and Vineyard (now Trump Winery), Pollak Vineyards, Veritas and Stinson Vineyards, all adept at the hospitality and marketing aspects of the wine trade.

There are also experimentalists such as Quartzwood, Lightwell Survey and Midland Construction who would all feel at home in the “wine ghettos” of California’s Central Coast.

Finally, there are audacious, talented producers who have attracted international attention in their early vintages – think of Le Pin as a comparison – such as RdV Vineyards and Ramiiisol Vineyards, both with the quality of their wines and the guts to charge more than US$100 a bottle for them.

GEOGRAPHICALLY DIVERSE

Virginia is a very geographically diverse state – from sea level in the east to high in the Appalachian Mountains 430 miles to the west. From north to south, the state stretches 200 miles between the 36th and 39th parallels of latitude.

A small section of its eastern region, cut off from the remainder of the state by Chesapeake Bay, lies on the pancake-flat Delmarva Peninsula.

Most Delmarva wineries here are in neighbouring Maryland, but one Virginian, Jon Wehner, in his 21st year at Chatham Vineyards, densely planted 37,000 vines on 21 acres, mainly Chardonnay and Bordeaux reds. “We are at 20 feet elevation with heavy moraine deposits,” he says, “and the combination of the bay at our doorstep [about 100 metres away] and the cooler soil means our bud break is usually later than the rest of the state.”

Visitor-friendly: Wineries such as Linden are tourist attractions in their own right

The bulk of Virginia is on the western side of the Chesapeake and begins with the rolling Tidewater region that gradually expands west, bordered on the north by the Potomac River and Washington, DC, until it reaches the hilly Piedmont region, which ranges along the north-south foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, a spur of the Appalachians.

Across the Blue Ridge is the somewhat narrow Shenandoah River Valley, its stream flowing north into the Potomac. “Our region is higher in elevation than the rest of the state,” says Lee Hartman, whose family is the first-generation owner of Bluestone Vineyard, “so our harvests expand later into the fall.”

Most of the state’s wineries, and the ones with the best reputations, are congregated in two areas – the Middleburg Virginia AVA (American Viticultural Area) just outside Washington, DC, and farther south in the rolling hills surrounding the university town of Charlottesville in the Monticello AVA. More recently, Shenandoah Valley AVA wines have received increased attention.

Although there are a total of eight official AVAs in Virginia today, they don’t yet have the same significance as those in California.

“AVAs in Virginia are way ahead of their time,” says Jeff White, owner of Glen Manor Vineyards along the Blue Ridge, whose family have farmed the area since 1787. “They are mainly designed for marketing purposes,” he continues, “and their boundaries weren’t devised because there was something extraordinary or special about them. It takes 100 or 200 years of experience to claim that.”

However, Nate Walsh, whose Walsh Family Vineyards is in the Middleburg Virginia AVA, sees potential in AVAs “if more producers would focus on them.

Right now, some are too big, so we need sub-AVAs with stricter guidelines”.

Virginia’s diversity of wine grapes can be viewed as a blessing or a curse – a blessing for those who love to sell and buy wine by variety, a curse to those who believe a region should be known for two or three “signature” grapes.

According to the Virginia Wine Marketing Board, the state has 11 varieties with more than 100 acres of each planted – Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay, Petit Verdot, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Viognier, Petit Manseng and Sauvignon Blanc – all vinifera – plus the hybrids Vidal Blanc and Chambourcin and one native American variety, Norton. Among Bordeaux varieties, there is some preference among growers for Cabernet Franc and Petit Verdot over Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot for their adaptability to the climate.

Nonetheless, some of Virginia’s most highly-rated wines have been Cabernet Sauvignons. Chardonnay seems to grow well everywhere and is prized for its versatility. But the sleeper among European varieties is Petit Manseng, the white grape from France’s southwest regions, a variety pioneered in Virginia by Law at Linden.

COLLECTION OF FAVOURITES

“For certain grape varieties, such as Cab Franc, Petit Manseng, Petit Verdot and Tannat, we can make as good wine as anybody,” Shaps says. It’s a collection of favourites echoed by other growers. “Tannat is wonderful to grow, is fairly disease-resistant and ripens mid-season,” Walsh adds. “The only question is whether you can tame it.”

For years, “serious” east coast producers believed only vinifera grapes could make superior wines. Many French-American hybrids, developed during Europe’s fight against phylloxera, have been widely grown for their winter hardiness and disease resistance. But wines made from them didn’t seem to taste as good, retaining some of the native American grapes’ pungent fruitiness.

Now that thought is being challenged, especially as new hybrids with more vinifera parentage are being developed by breeders at New York’s Cornell University and elsewhere. Relatively new varieties, such as the red Noiret and the white Traminette and Chardonelle, are also finding favour even among some legacy growers.

But younger, more experimental winegrowers, such as Virginia natives Sarah Searle and Ben Sedlins, are spearheading the re-evaluation of hybrids. The couple own neither vineyards nor a winery, but Sedlins oversees a dozen vineyards where newer hybrids dominate, and where they source grapes for their Quartzwood brand of mainly hybrid wines.

“My favourites are Noiret and Chardonelle,” Sedlins says, “but I am really excited about the new Italian VCR hybrids that I’ve just planted in three vineyards. The breeders at Cornell and Minnesota [universities] are still mainly concerned with cold hardiness, but the Italians are breeding for taste,” with less American grape parentage. Glen Manor ’s White offers a reminder as to why for years people avoided planting wine grapes in Virginia, period. “Every variety we grow is difficult,” he maintains, “because Virginia is one of the wettest regions in the world.”

International appeal: RdV attracted the attention of consultant Eric Boissenot

One promising aspect of the Virginia wine industry is its diverse ownership mix – from experienced, well-financed outside investors to farm families who have become winegrowers, to small, garagiste-style producers, some without their own facilities.

Brothers Ben and Tim Jordan have been winemakers for themselves and others, as well as consulting. Last year, they launched Common Wealth Crush, centrally located to serve wineries in the Shenandoah Valley and Charlottesville areas.

“Some clients want their wine made from start to finish,” says Lee Hamilton, a partner in the venture. “Some are already set up, but have run out of space. And we’re excited about our incubator programme. We are presently helping start two new brands from birth, and we’re looking especially to those from underserved communities with less access.”

Walsh Family offers a “winemakers studio”, working with about a dozen producers, including Quartzwood. “We wanted a programme where we could custom crush and make our own wines,” Nate Walsh says. “But it’s great to be surrounded by other winemakers.”

The sales and marketing lynchpin of most Virginia wineries, regardless of size, financial backing or quality of product, is tasting room sales, wine clubs and other direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales. Long before California caught on, east coast producers also pioneered winery events such as informal concerts and weddings for added revenue. Collectively, Virginia wineries host about 1.45 million tourist visits annually. However, some assertive producers are designating a segment of their production – 20% is a goal frequently cited – to be sold to regional restaurants and retail shops through wholesalers – either national ones such as Winebow or smaller, regional firms. For example, Glen Manor ’s White says his 20% is distributed to buyers in about 26 different states.

YOUNGER CHALLENGERS

Charlottesville-based importer/ distributor Williams Corner has an international portfolio, but also distributes about a dozen Virginia brands. “We represent mainly younger challengers who are more experimental, which is what our customers want, and fewer legacy producers,” says CEO Nicolas Mestre. While, he says, wine shops consider Virginia producers as good-quality, good-price options, in nearby Washington, DC, restaurateurs still prefer European and California wines. An exception is the Inn at Little Washington, a Michelin three-star restaurant in the Virginia countryside, with several local bottles on its big wine list, but seldom wines by the glass.

Meanwhile, work continues at several levels to improve quality and to extend Virginia’s reputation as a world-class region. Local colleges and universities have wine teaching and research programmes, but nothing to compare with those at California’s UC Davis or New York’s Cornell University.

However, there is a very robust catalogue of practical research being done through the state-supported Virginia Winemakers Research Exchange, which directly involves a multitude of winegrowers.

“Winemakers meet regularly to discuss experiments and propose ideas for new ones,” says oenologist Joy Ting, who oversees research. “We are presently conducting around 50 different vineyard experiments, some multi-faceted with different controls and treatments. We make sure that winemaking is of sufficient scale with multiple barrels,” in order to rule out spurious results.

Additionally, most producers believe they have a strong advocate in the Virginia Wine Board Marketing Office, headed by Annette Boyd. Many of its efforts have involved DTC and tourism programmes designed to increase tasting room traffic, but it has also extensively courted foreign wine media, especially UK journalists.

“In 2010, The Circle of Wine Writers came to Virginia for a week-long tour,” Boyd says. “Then, in 2011, the Circle in London asked us to host its Christmas party. After that, we have continued to connect with several of those writers, and many attended our booth at the London International Wine Fair.”

Virginia winegrowers have retained several French consultants in recent years, including Michel Rolland at Kluge, before it became Trump. Eric Boissenot was so impressed with the early promise of Rutger de Vink’s RdV estate reds that he asked to consult there and continues to do so today.

A few Virginia producers, especially Zonin-owned Barboursville, are exporting to European markets, a necessity for the region in order to gain recognition beyond the US.

Overall, the internationalist Shaps and many of his colleagues remain optimistic. “We’ve got a way to go to be recognised like the other great wine regions,” Shaps says, “but the word is getting out.”

Related news

Zamora Company to distribute Bottega sparkling wines in Spain

Cabernet Franc on track to become the official grape variety of New York State