Will nutrition and ingredient lists on wine labels boost sales?

Winemakers can’t talk about health on labels, but there is a worthy argument arising on how they can (and should) talk about ingredients and calories. Kathleen Willcox reports.

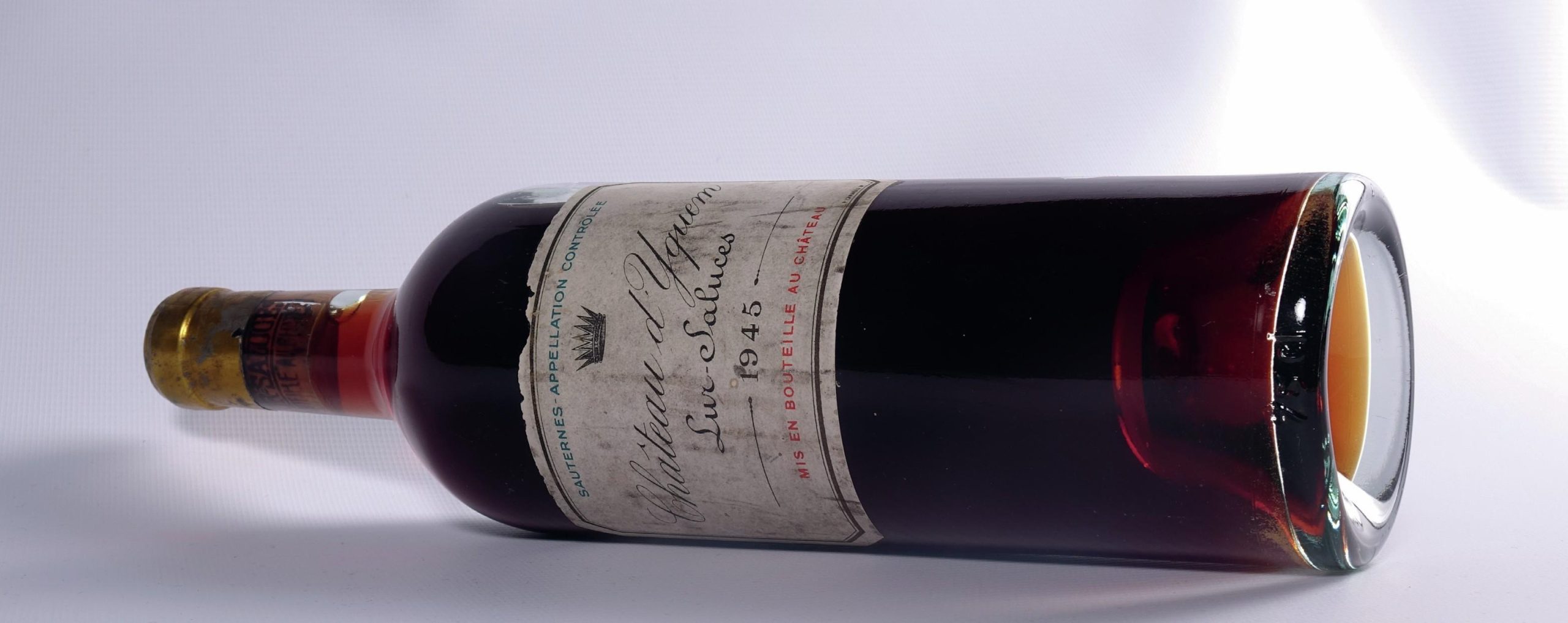

Pick up a bottle of grape juice, and you have a wealth of information in your hands. At a glance, you know if it’s made from fresh grapes or concentrate, and if it has other ingredients, like added sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, food dye, ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) or citric acid (for tartness). You can also see how many calories, carbs, protein, sugar and fibre it contains. Pick up a bottle of fermented grape juice, though, and you find out the name of the producer, its region and perhaps even vineyard of origin, its vintage and, frequently, the grape or grape varieties from which it was made.

“Historically, we’ve chosen to accentuate the romance of wine,” says Bill Leigon, a partner at L&S Vintners, and previously the founder of Jamieson Ranch Vineyards and president of Hahn Family Wines. “But in the process, especially in recent years, we’ve ceded ground to other categories in the alcoholic beverage space that are clearly communicating their ingredients and nutrition, like hard seltzer. This is especially frustrating because from a health standpoint, wine is much purer and quote-unquote healthier than seltzer, but we can’t put that information on our label in so many words.”

But producers can, Leigon insists, put information on labels that allow people to draw their own conclusions, and in the process, bring new wine lovers to the table.

Declining sales due in part to lack of transparency?

The industry appears to be at a crossroads, but there are signs that the road headed greater transparency and communication is the one the public would like to see vintners head in. Americans bought less wine last year than they did in 2021, according to Rob McMillan’s annual State of the Industry Report. And while the effervescent growth of hard seltzer has fizzled somewhat—after growing 12% year-over-year in 2021, it declined 5.5% in 2022—it is still poised to be worth $57.34 billion by 2030, with a compound annual growth rate of 22.9%, according to a report from Grand View Research.

Most concerning is the decline in consumption among consumers ages 59 and below. The only growth segment in wine is in the 60+ set—not a recipe for explosive, or even continued sales gains. Seltzer, on the other hand, has cornered the youth market, driven by their desire for a lower-calorie, lower-carb and gluten free lifestyle—facts that seltzer producers communicate right on their cans.

“But that’s wine too,” Leigon says. “People just don’t know it, because we’re not telling them.”

A growing contingent of producers and industry pros are pushing for more transparency of ingredients and nutrition on the bottle. Consumers, generally speaking, want to see ingredients and nutrition, according to multiple studies. Ingredients have a moderate influence on 63% of buyers in the US, according to a survey from the International Food Information Council, and 68% want ingredient and nutrition information on beverages, according to a study from data and insights firm Kantar.

And as it turns out, producers that have been resisting the siren song of data and facts in lieu of mystery and legend, may be forced to succumb: after making nutritional labels optional in 2013, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) has signalled, in response to an executive order from President Biden, that it will prioritise creating more robust labelling requirements. The TTB is expected to greenlight allergen and nutrition labels by the end of 2023, with ingredients getting the go-head in 2024. The European Union (EU) is in the process of requiring ingredients on labels, via QR codes.

Meanwhile, vintners who have chosen to share more information about ingredients and nutrition — for a variety of reasons — are finding their efforts rewarded by younger consumers.

Ingredients transparency

The reasons for a winery’s decision to share their ingredients can be as various as the ingredients themselves. But it all boils down to one thing: showing, essentially, what isn’t in their wines.

“We were among the first to put our ingredients on the label, after Bonny Doon,” a brand that pioneered it in 2007, notes John Olney, head winemaker and COO of Cupertino’s Ridge Vineyards. “Initially, we did it because we were alarmed by the number of ingredients the TTB was allowing in wine. You go back 100+ years, and the only things you had in wine were grapes and sulfites, for preservation. But starting in the 1970s and accelerating through the early 2000’s, the TTB approved more than 60 additives, including mega purple and velcorin, a chemical that can be poisonous in large doses.”

And while Ridge began including ingredients on its label in 2011 to point out, subtly, what wasn’t in the wine, Olney sees it now as a bridge to health-conscious consumers.

“Younger people want transparency and disclosure,” Olney says. As Olney alludes to, younger consumers—especially members of Gen Z—want more than performative words and guarantees from brands. They want transparency and action, according to consumer

analytics firm ThinkNow.

Joe Webb, winemaker at Foursight Wines in the Anderson Valley, concurs. “It was a real battle getting ingredients and the fact that we’re vegan a vegetarian-friendly on the label,” Webb says. “We started in 2007, and didn’t get it approved by the TTB until 2010, but from what I understand, it has gotten much easier. And people want to know. As a consumer myself, I want to know.”

Partner Content

John Grochau is introducing ingredients on his Willamette Valley Grochau Cellars labels via QR code this July with the winery’s biggest SKU—the 2022 Commuter Cuvee Pinot Noir. Labels for his other wines will also disclose ingredients via QR code in 2024. Grochau sees it as a way to prove to leery consumers that, despite the competitive price point (US$20-US$25 for the Commuter), the team at the 16,000-case winery is still making low-intervention wine without chemicals, like producers who sell bottles for thrice the price.

“My whole winery is built on making premium wine at value prices,” Grochau says. “Our competitors offer much more manufactured wines, and I felt like sharing our ingredients was the best way to show what we do, and what we don’t do.”

Nutritional transparency

Other wineries are also adding nutritional information, because it’s often unclear how many calories one serving has. Alcohol levels are a clue, but sugar levels—the label “dry” doesn’t have any legal meaning in the US — are essentially a black box.

“We include ingredients and nutritional information on our labels, and the decision to lean in on total transparency came early in the process,” says Dave Schavone, the co-founder of the L.A.-based 1,500-case winery RedThumb. “We knew we didn’t want to have a traditional wine label, and since we’re very proud of the standards we hold our wines to, communicating those standards on the labels became our focus. Having traditional ingredient and nutritional declarations seemed obvious at that point.”

The winery launched in 2021, and so far, the strategy has worked.

“We were pouring our wines at the New Orleans Wine & Food Experience, and our table was placed next to that of a very large conventional producer out of California,” Schavone says. “Many of the wine fans asked us a few questions around our labelling and there was a lot of engagement, but what was most enlightening was hearing them ask for the same information from the very well-known company next door. It let us know that there was at least a curiosity surrounding wine ingredients, even amongst conventional wine drinkers.”

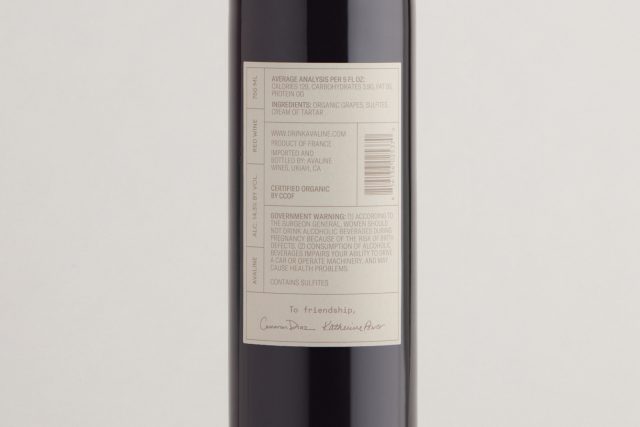

The L.A.-based wine brand Avaline, created by actress Cameron Diaz and entrepreneur Katherine Power earned a lot of flak for, among other things, the brand’s unparalleled devotion to label transparency when they launched in 2020. And while they’re probably still not poised for a perfect score in Wine Spectator anytime soon, their bare-knuckled approach to focusing more on their sugar and calorie levels than the romance of their terroir speaks for itself.

Avaline has scaled up from 25,000 to nearly 100,000 cases in annual production in three years, is now the #2 organic wine brand in retail, the #1 brand in the ultra-premium price segment and it has ground its direct-to-consumer channel by a factor of 4.4 year-over-year.

“If I eat a cookie, I want to know what’s in that cookie,” says winemaker Ashley Herzberg. “Why should wine be any different? I think there has been a huge turning-away from wine on the parts of Millennials and Gen Z because there’s no information about what’s in the wine. By bringing that information into the picture, we think it’s a win for everyone.”

At Scheid Vineyards, they’ve also started spelling out their nutrition facts and organic winemaking values through ingredients.

“Of the 850,000 cases we produce, 92,000 were for our leading ‘Better for You’ brand Sunny With a Chance of Flowers, which has included nutrition on the back label since its introduction in 2020,” says Heidi Scheid, the winery’s executive vice president. The label calls out key attributes like “zero sugar, 9% alcohol and 85 calories per 5 ounce serving.”

They recently started adding ingredients on The Grandeur line, which now carries a “Made with Organic Grapes” certification, with ingredients that simply include “organic grapes, tartaric acid (for stabilisation) and sulfites.

“As the demand for transparency continues to grow, we feel that nutritional and ingredient information is appreciated by our target audience,” Scheid says. “The wine industry is confronted with the challenge of attracting Millennials who aren’t purchasing wine at the same rate as previous generations. We see this is a way to attract the younger generation and potentially boost sales.”

Jamie Araujo, founder and vintner at Trois Noix in the Napa Valley, feels like the wine industry has a blind spot when it comes to providing information on wine labels.

“We’ve been talking about how we want to revamp our wine label for a few months now,”

Araujo says, adding that they produce around 3,000 cases annually, and hope to include the changes in the next bottling a few months from now. “The industry can be very dismissive — intentionally or not — of what consumers actually want to know. We’re going to start putting gluten-free and vegan on the label, and we’ll also be adding ingredients and nutrition. In many ways, it’s very easy and straightforward. There’s so much talk in the industry about making wine more accessible — and there are very big picture items involving inclusion and the way we welcome people to the table that we have to deal with — but there are also some very simple things like sharing what’s in the wine.”

For the sommelier co-founders of Nossa Imports, Dale and Stephen Ott, these changes are a breath of fresh air.

“Transparency is necessary, and it when it’s mandated by the TTB and the EU, it will turn this industry on its head,” predicts Dale Ott. “Out of the three major alcohol categories (wine, spirits, and beer), wine has not caught up to changing times and generations over the past many decades in terms of marketing, inclusivity, and transparency. What’s in wine should not be shrouded in what could be called pretentious mystery. More transparency will allow consumers to confidently shop for and select wines that fulfil their personal ethos regarding low-intervention and quality.

Instead of fretting over “shifting demographics of wine consumption,” Stephen Ott says, “wineries should adopt more transparent and clear labelling conventions. This will provide the opening” that “millennial and Gen Z” consumers have found elsewhere.

Since 2007, the proportion of wine sold to people ages 30-40 has dropped -1.27%, and the proportion of wine sold to people ages 40-50 has dropped -7.36%.

Is the battle over putting calories and nutrition just a tempest in a teapot? The screaming outrage that resulted when photos of a wine list divided by calories emerged online suggests otherwise. Turning negative growth into positive growth surely isn’t just a matter of splashing “100 calories per serving” on a bottle of Pinot. But it may help turn this slow-moving ship around.

Related news

Queen Camilla gives speech at Vintners Hall

Master Winemaker 100: Alberto Stella

Australian Vintage sales dip 1.7% as turnaround plan targets stronger second half