The Big Interview: Caroline Frey

French winemaker Caroline Frey tells Colin Hay how global warming is changing the taste of our favourite wines.

While few would deny the effects that global warming is having on the wine trade, there aren’t many who are prepared to be quite as searingly honest as Caroline Frey about its effect on their work on the front line. Nor many who have had a ringside seat to watch the fight play out in different French regions, each of which has its own set of unique climatic challenges to grapple with.

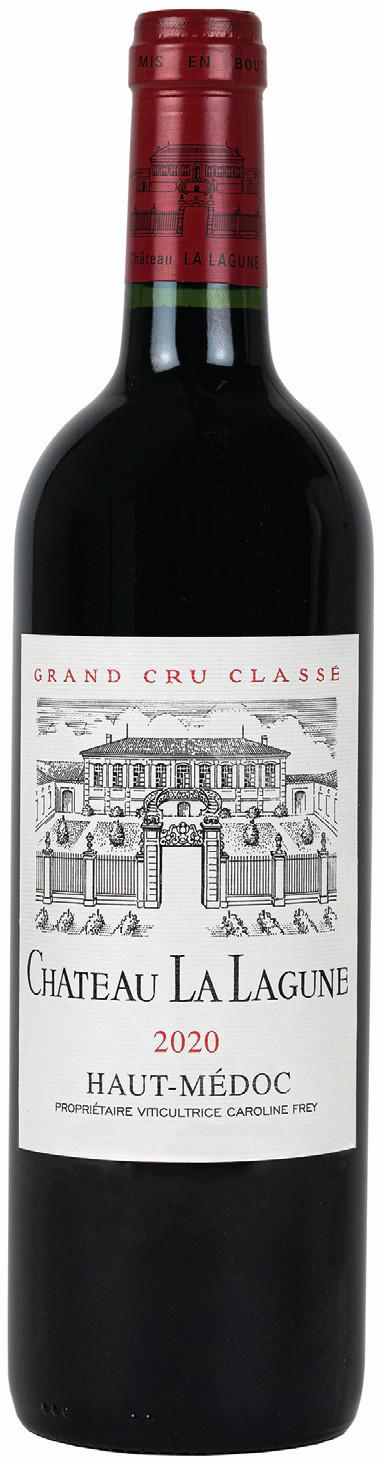

As winemaker for Château La Lagune in Bordeaux, Château Corton in Burgundy, and Paul Jaboulet Aîné in the Rhône, Frey has witnessed the many micro-aggresions that climate change brings, and she is hugely passionate about wielding the tools of organic and biodynamic viticulture to combat them.

Over a two-day visit and vertical tasting of Hermitage La Chapelle and of flagship wine Château La Lagune, Frey tells the drinks business how her experiences at these French properties have led her to the conclusion that “soil is everything”. “Over the past 20 years, climate change has, of course, affected the taste of our wines,” she says. “The taste of the wine in the glass and the health of the terroir are intimately interconnected. It is by tending and preserving a soil capable of regulating the effects of the climate that we preserve the identity of our wines.”

Batting away any suggestion of her wines having a particular style, she adds that “a style is a fashion, and fashions pass. I prefer to talk about the core identity of a wine, its DNA.”

To put it another way, Frey is interested in searching for the “deep soul of a wine”, and how winemakers can preserve that special link to the place from which the wine comes. “I believe that the quality of any wine comes from its terroir. That is why we attach so much importance to the proper functioning of the ecosystem in which our vines grow, and why we do everything we can to preserve it.”

Understanding these intricate and entwined pathways of roots, organic matter and the living creatures that exist in and around them “requires a profound attention to all that takes place underground – the humus, the microorganisms, the mycelium – as well as all that takes places above ground – the fauna and flora, the microclimate and the surrounding biodiversity”, Frey explains.

MORE THAN TERROIR

That said, her vinous creations are by no means the result of the terroir alone. Careful work in the vineyard and in the cellar are instrumental to crafting the elegant expressions that her châteaux are known for. “The terroir is, in my eyes at least, what matters most. But although it is the necessary precondition of greatness, it is not in itself sufficient,” says Frey. “It is, if you like, the musical score that nature has composed; it still has to be performed.”

Over the years, Frey’s three French wine estates have been certified organic and biodynamic. As well as extensive changes implemented in the vineyard, Frey has also initiated various green projects, such as planting 1,200 species of hedges and more than 5,000 sq m of fruit orchards to increase biodiversity at her sites. Additionally, she has overhauled the packaging of the chateaux’s wines to use natural vegetable inks, recycled materials, and considerably lighter bottles.

When asked whether she thinks that climate change has been kinder to the Médoc, where Château La Lagune is based, than it has to the Rhône, which houses Paul Jaboulet Aîné, Frey pauses to consider her answer. “Yes, but things are probably a little more complicated than that,” she says finally. “The two contexts are, in the end, very different, and it may not be terribly helpful to draw comparisons. The soils of Bordeaux would probably not support the climate of the Rhône, and the inverse would probably not work well either. When it comes to climate change it’s not really a question of one being more severely impacted than the other. I would not draw that conclusion from my experience, anyway. We have to adapt in both regions to allow the vines to withstand intense periods of heat but, perhaps above all, long periods of drought punctuated by occasional substantial rainfall.”

Frey is fortunate to be able to tap into the expertise of her teams across the three wineries. “Each region has its own terroir and its own history. You really have to respect that. But, of course, I always try to see if something that works well in one region might be interesting for the other,” she says. “A lot of this comes from the complimentary skills of the teams. For example, at La Lagune, our culture manager is very interested in biodynamic plants and compost. At Jaboulet, we have a culture manager who is very competent in top grafting and massal selection. When we pool the skills of both teams together, we find we have a lot of possibilities.”

Each winery team must also be finely attuned to the specificities of their property’s surroundings. At Château La Lagune, for instance, 40 hectares of protected wetlands circle the vineyards, which Frey says are “extremely important for the water cycle”. Contrastingly, at Paul Jaboulet Aîné there is abundant forest, which is essential for promoting biodiversity.

Of course, there are similarities, too, between the estates. Frey says she has witnessed more frequent episodes of frost and hail in all regions in the past few years, but the fact that in the Rhône Valley the vineyard is dispersed, rather than from a single block like at La Lagune, means that damage there from these particular climatic extremes is limited.

It’s the risk of drought that concerns her most. “Even though 2021 was a rather rainy vintage, drought is now an established and proven trend. This is perhaps our biggest challenge: to ensure that the water resources are adequate for the vine to function properly until harvest. Only the soil can play this reservoir role,” she says.

Frey staunchly maintains that maturity must come from the plant and not from the mechanical effects of heat, for example. “A soil that has a good amount of humus inside it is capable of retaining water like a sponge and releasing it when necessary. For this, biodynamic viticulture helps us a lot.”

On the topic of drought, one might reasonably imagine that the very stony soils of the hilly Hermitage vineyard, with its fully southern exposure, may become too dry or too hot to produce fine wine before long.

“Think again. It is not by accident that these are considered great terroirs,” says Frey triumphantly.

“It is all in the soil, which allows the vine to sink its roots very deep into the ground, to wrap itself around the pebbles, thus increasing its surface exchanges, to find water in limestone concretions formed under the stones by bacteria, or in deep clays.” Conversely, in cooler, wetter vintages such as 2021, the impressive capacity of the stony soil on the hillsides of La Chapelle to drain so well was crucial. “The white wines in particular were able to take advantage of this to develop excellent balance and intense aromatics,” says Frey.

The barrel room at Château La Lagune

It’s clear that Frey trusts deeply in the natural resilience of the soils, and it is for this reason that she deliberately tries to be as hands-off as possible. “During periods of drought and heat we leave the vines alone, so as not to stress them even more. The key is the organic-matter resource. By limiting the working of the soil, we avoid a rapid mineralisation,” she says.

“The addition of biodynamic compost and the grinding (broyage) of the vine shoots makes it possible to restore organic matter. We sow green fertilisers in the autumn, and lay them down in the spring using the Mexican method of the faca roller (to encourage their composting). The aim is to preserve soil quality while at the same time nourishing it.”Frey sees great potential in the use of organic-indicator plants for helping growers to understand what the soil needs and when. “That is just one of a number of new techniques we are starting to use,” she reveals.

“We are also trimming less, and leaving more foliage around grape bunches to maintain shade. We use certain preparations, such as silica, after the harvest, which help to reinforce the vines’ natural reserves to help them regenerate through the winter. It’s all about the small details; together they make a difference.” In short: “Viticulture must be an accompaniment to nature, and not a struggle against it”. Yet, at the same time, Frey concedes that “each year we need a fair dose of good fortune if we are not to lose our harvest.”

SMALLER GRAPES

Frey has noticed the grapes on her estates now tend to be smaller with thicker skins. “Accordingly, we have greatly reduced the extraction we seek, with less frequent and gentler pumping over and pigeage. Almost all of our extraction is now achieved simply through natural maceration. This gives a fabulous texture to the wine,” she says.

Following detailed research and development, Frey is confident that organic and biodynamic wines taste different from one other. “We have carried out extensive comparative trial tests in the vineyard, then vinified the trials separately until bottling. This has allowed us, over a sustained period of time, to regularly blind taste the different modalities. The results are clear. We have a consistent and strong preference for biodynamic wines. They are purer, more luminous, more radiant, and fresher,”she says.

Looking to the next 10 years, Frey suspects her greatest anxieties will be about climate change. But she remains confident that she will find a solution, as she has done so many times before. “Nature is full of resources and so are we.”

Caroline Frey at a glance

After graduating from Bordeaux University, Frey took the helm of her family-owned Bordeaux estate Château La Lagune in 2004. When her family bought Paul Jaboulet Aîné in the Rhône Valley, in 2006, and Château Corton in Burgundy, in 2014, Frey was tasked with making wine on all three estates, a task she took on with relish, initiating organic and biodynamic practices to encourage healthier soils. She also manages a private vineyard in Valais, Switzerland. In 2017, Frey received the Chevalier de l’Ordre National du Mérite, awarded for her work in agriculture, viticulture and the environment, as well as the protection of birds in her wine estates. In 2021, Frey won The Amorim Biodiversity Award at The Drinks Business Green Awards 2021 for her team’s work at Paul Jaboulet Aîné, and in the 2022 iteration of the same awards, she was commended for her work in benefiting the richness of species at Château La Lagune.

Related news

Areni Global: 'We have to find a way to make wine consumption safer' for women amid spiking fears

All the medallists from The Global Cabernet Franc Masters 2026