Show of strength: the Liv-ex Power 100

This year ’s Liv-ex Power 100 showed that wines from Burgundy producers are flexing their muscles in the secondary market. But with very few able to afford them, how long will their supremacy last?

Last year ’s Liv-ex Power 100 was a ‘rebalancing act’ – the Covid-19 pandemic and the buying spree it unleashed propelled the world’s great fine wine labels back to the top of their perch, from which some had been unseated in 2020. Both the 2020 and 2021 rankings highlighted an important trend in the secondary market; greater diversity, and the ongoing move away from Bordeaux. In contrast, this year ’s Power 100 is more focused. One region in particular dominates the rankings – Burgundy.

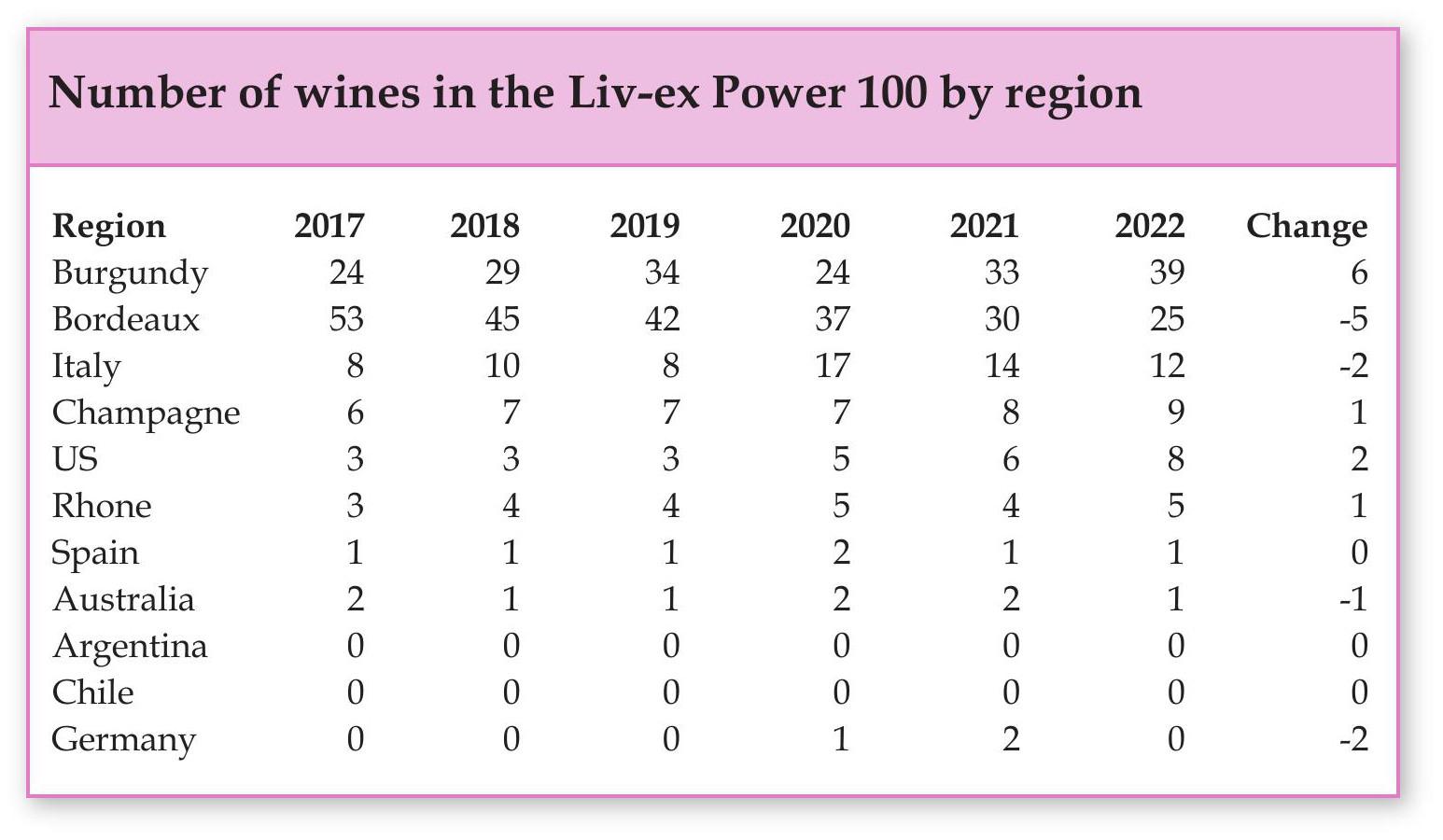

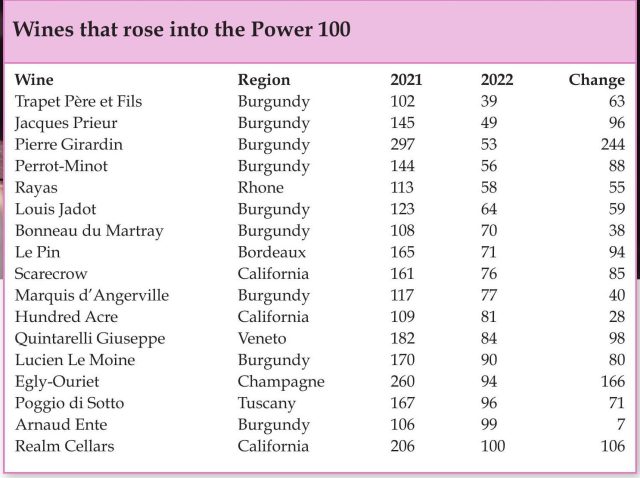

Supercharged by market confidence, ready money, and the anticipation of a tiny 2021 release, Burgundy’s momentum was building in last year ’s Power 100, with big price performances and a rise in the number of wines ranked in the top 100. This year, Burgundy added six more entrants, taking its total to 39; its highest ever total, and the highest number since the last Burgundy surge, in 2019.

Champagne too saw its 2021 momentum spill over into 2022, as collectors sought value and portfolio diversity. Between them, Burgundy and Champagne siphoned off 9% of the total market share from other regions over the year, largely at the expense of Bordeaux and Italy.

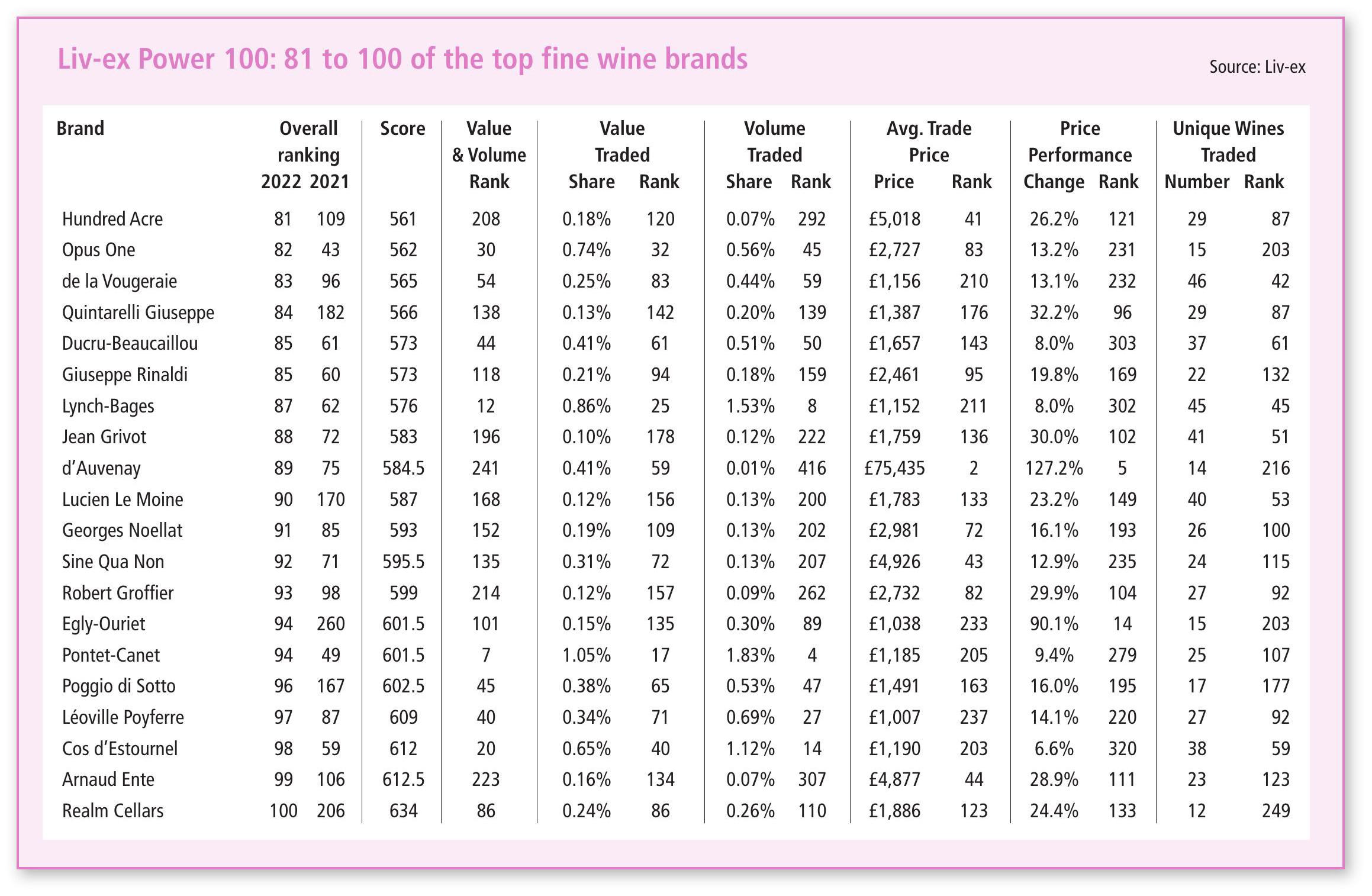

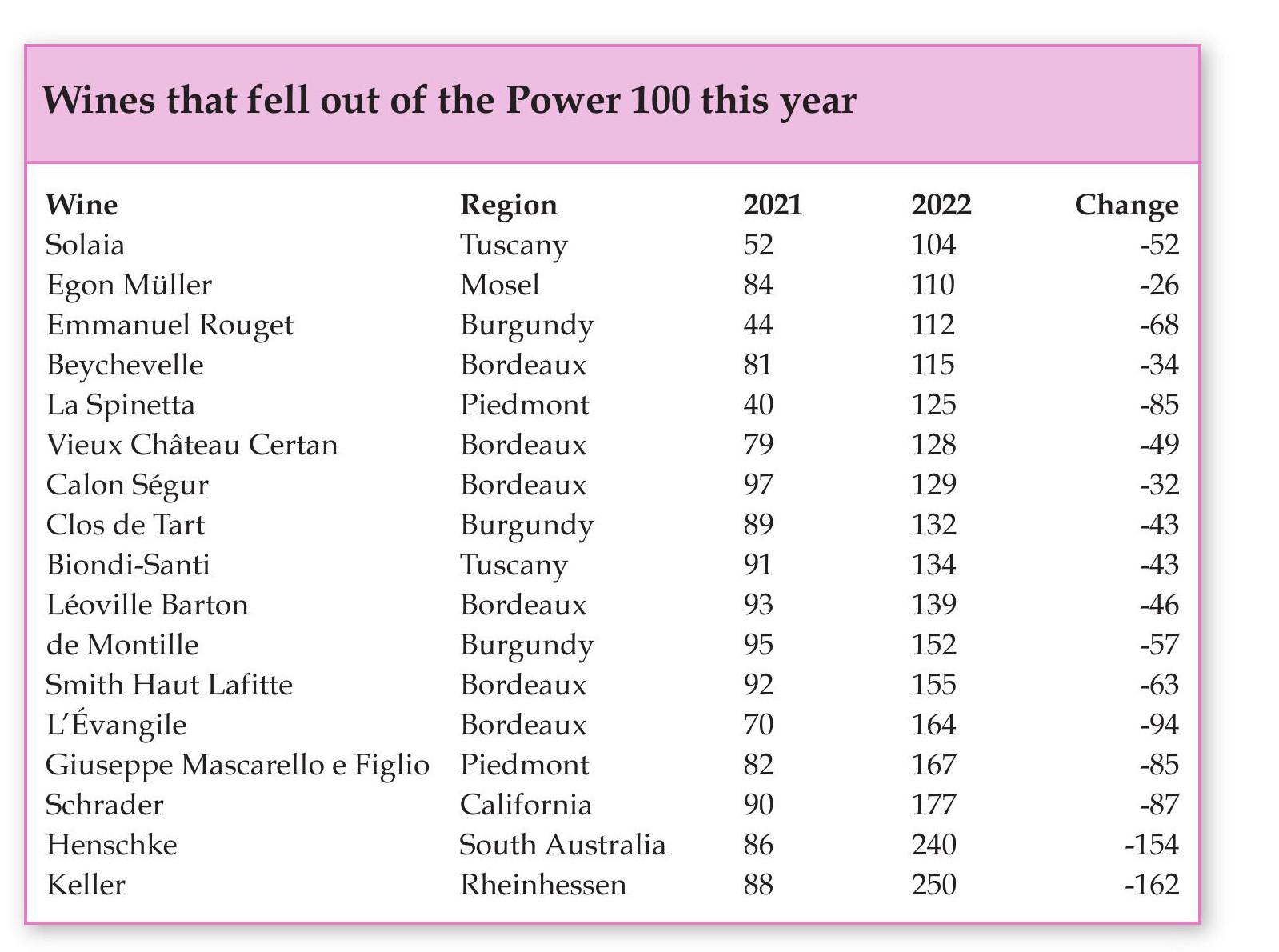

With that in mind, we can see (in part) why this year ’s list looks the way it does, and why some of the previously highflying Italian and Californian brands have slipped down the rankings – for this year at least. This is not to say that there has not been demand for other regions. Of the 422 wines that qualified for the Power 100 this year, fewer than 30 had a negative average price performance – and none in the top 100 itself.

As always with the Power 100 there are some key factors to bear in mind. The data analysed covers the year from 1 October 2021 to 30 September 2022.

The rankings are based on several weighted criteria, of which price performance, while important, is only one. As such, it is worth looking where each wine ranks according to each criterion, as well as the overall ranking.

For example, a Burgundian estate may rank highly for the number of its wines that were traded, the cumulative value of that trade, average price per case, and price performance, but its trade volume may be quite small. By contrast, a Bordeaux estate could rank highly for its trade value and volume, but is likely to rank lower for the number of wines being sold and its price performance. Looking at the rankings in detail allows for a more nuanced view.

Liv-ex Power 100: How it works

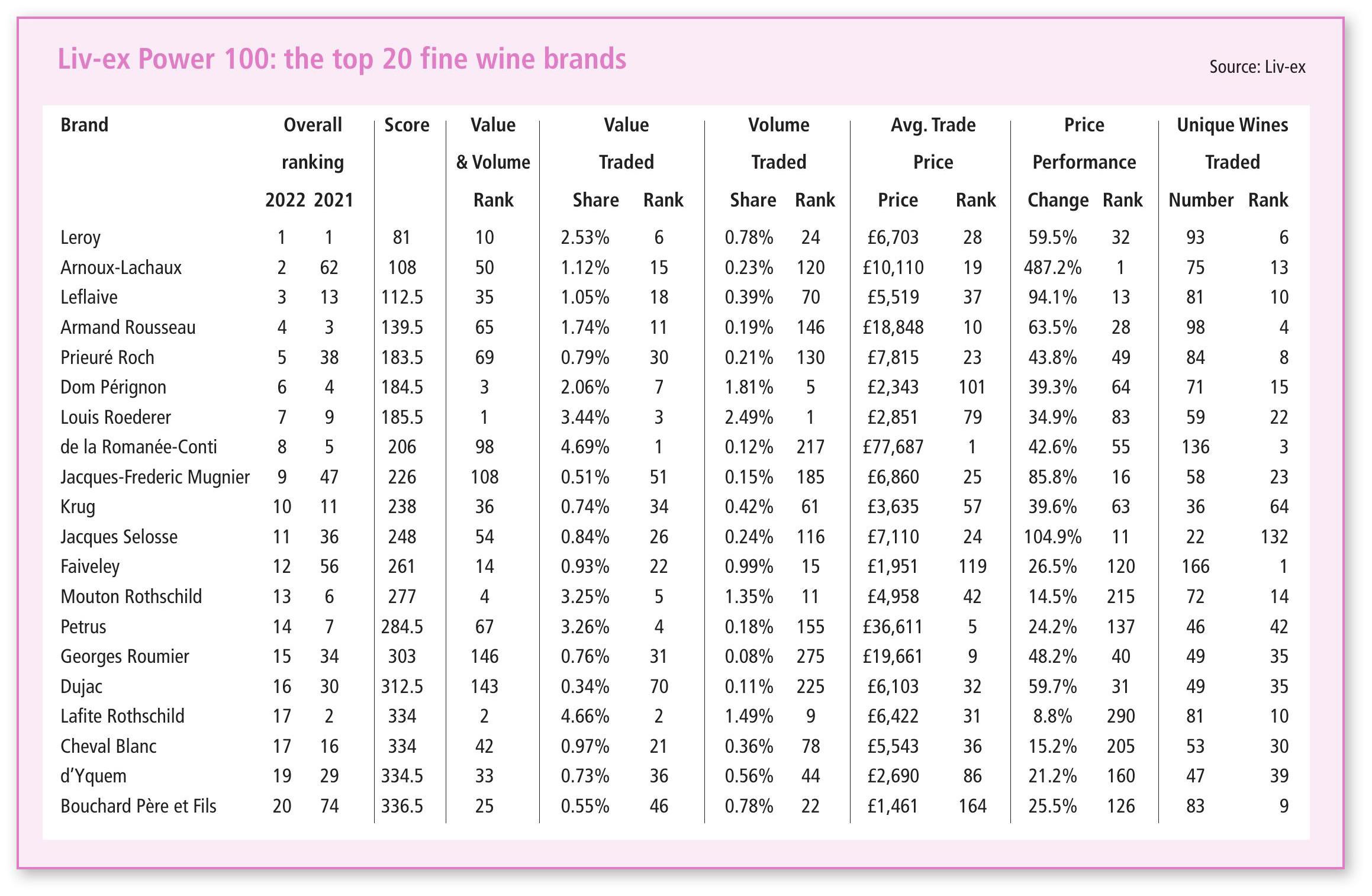

- To calculate the rankings, we took a list of all wines that traded on Liv-ex in the last year (from 1 October 2021 to 30 September 2022), and grouped these by brand. As is now standard, Burgundy labels with both maisons and domaines were combined as one. We then identified brands that had traded at least three wines or vintages, and had a total trade value of at least £10,000.

- Brands were ranked using four criteria: year-on-year price performance (based on the market price for a case of wine on October 1 2021 with its market price on September 30 2022); trading performance on Liv-ex (by value and volume); number of wines and vintages traded, and; average price of the wines in a brand.

- More than 12,332 different wines were traded on the exchange in this period. These were grouped into 1,694 brands, of which 422 qualified for the final calculation. The individual rankings were combined with a weighting of 1 for each criteria, except trading performance, which had a weighting of 1.5 (because it combined two criteria).

TOP 10

For the first time ever, no Bordeaux wines feature in the top 10. Not a single First Growth from either bank.

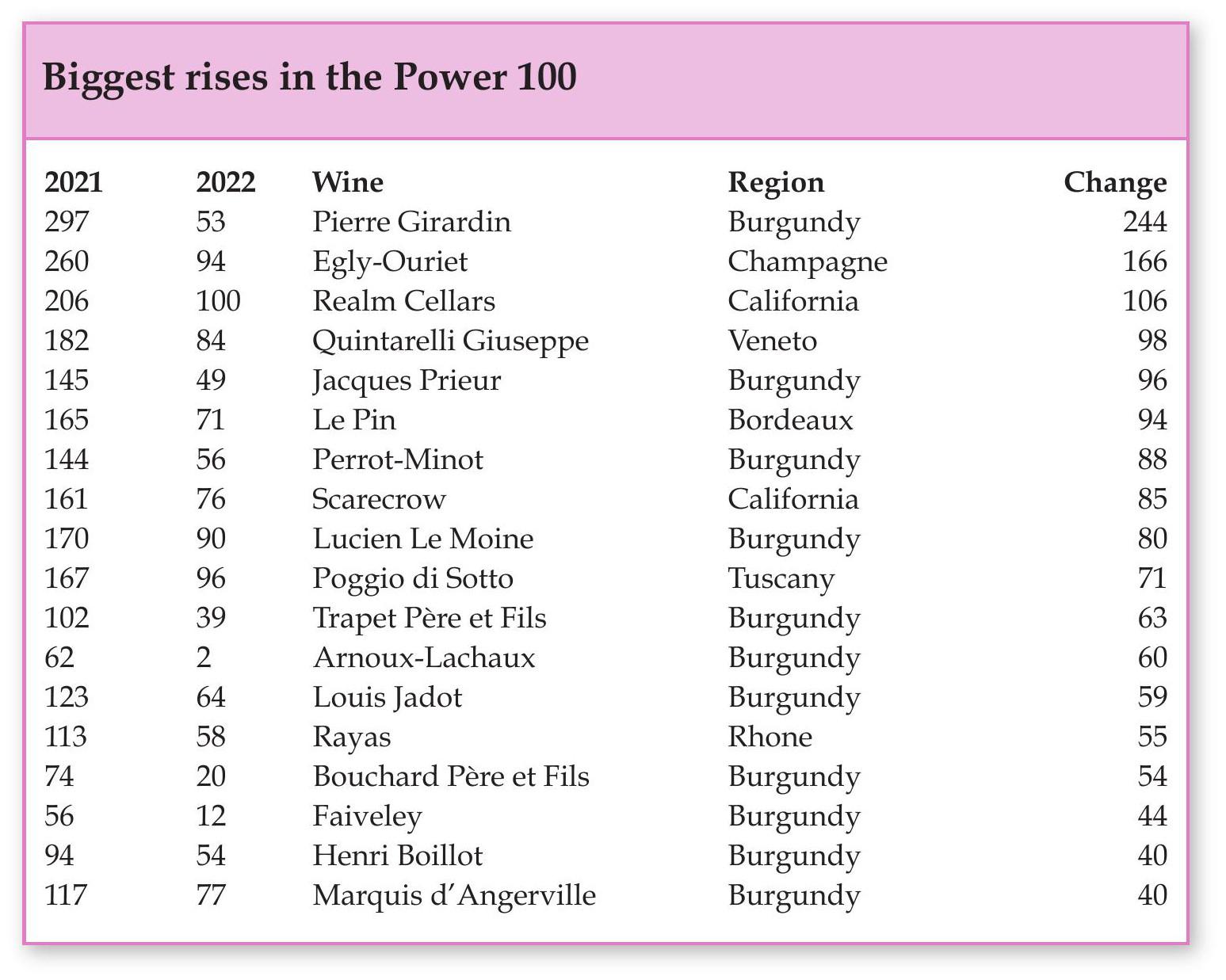

This year they have been usurped by Burgundy and Champagne. Four Burgundies and one Champagne have risen to displace Château Lafite Rothschild (2ndlast year), Château Mouton Rothschild (6 th), Pétrus (7 th), Sassicaia (8 th) and Château Margaux (10 th). The biggest risers into the top 10 were Jacques-Frédéric Mugnier (up by 38 places), Prieuré Roch (33 places), and Domaine Arnoux-Lachaux (up by 60 places). At the top for the third year in a row is Domaine Leroy. As our methodology explains, we combine maison and domaine labels under one brand. For Leroy this is both a strength and a weakness.

On the plus side, it significantly enlarges the pool of wines recorded as trading at what are high volumes for Burgundy. It also provides a major boost to the brand’s total trade value.

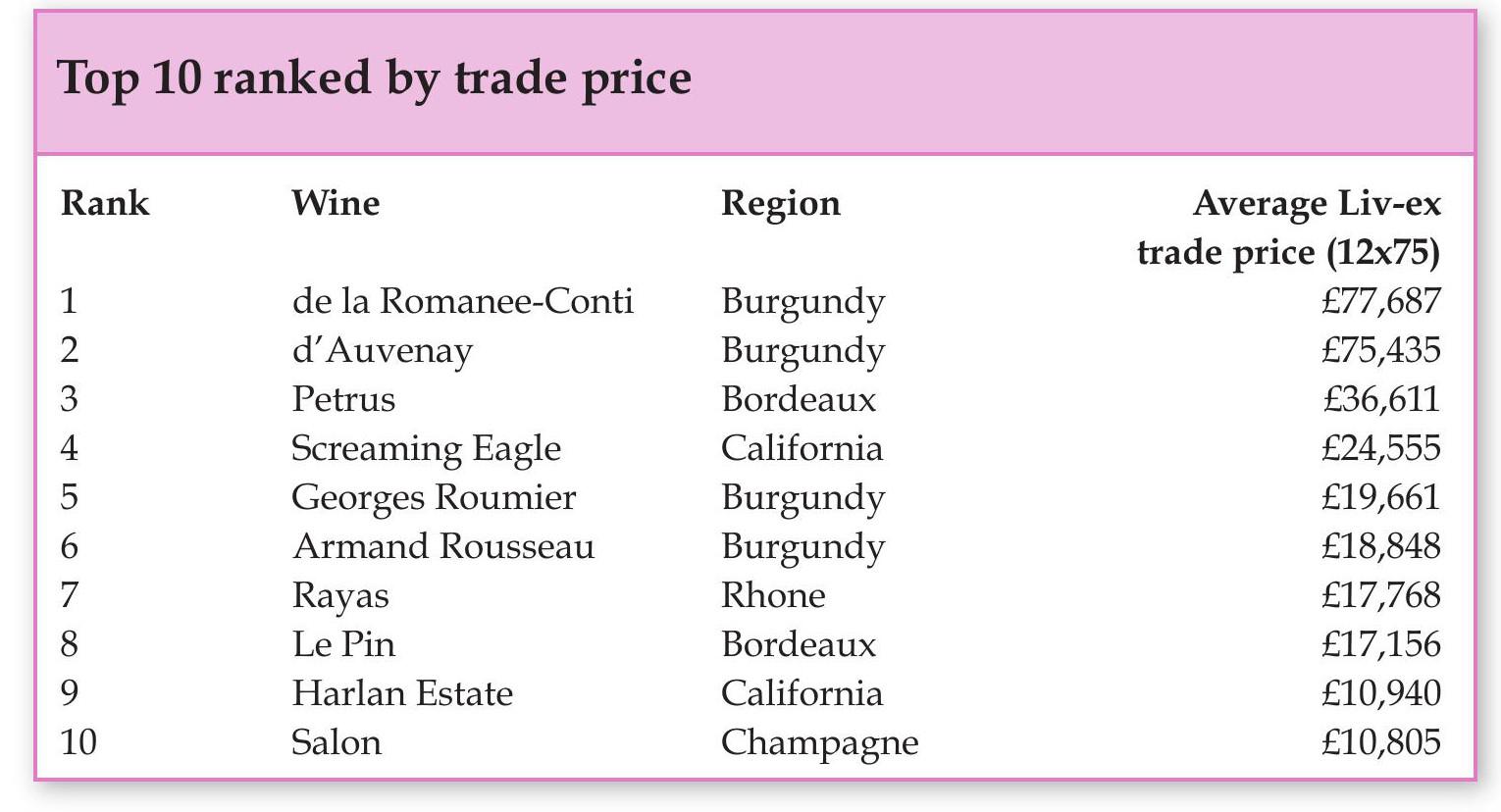

On the other hand, the inclusion of the maison wines significantly dilutes the average trade price. Those who have looked recently at the cost of a Grand Cru from Domaine Leroy will know they are not bought at £6,700 per dozen anymore – or even in packs that large either.

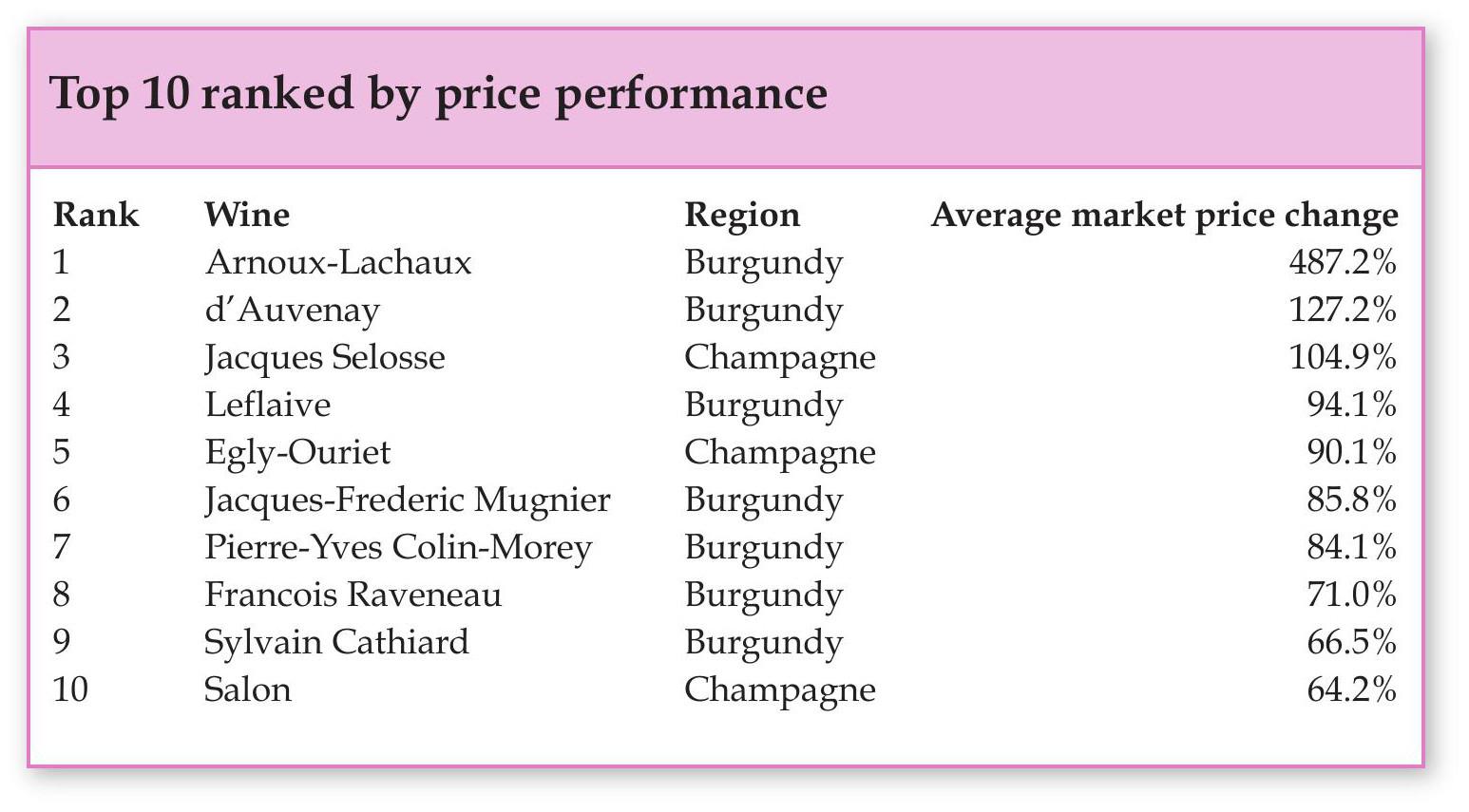

However, it demonstrates the continued power of the Leroy brand. Such is the clamour to taste these wines, yet so limited is supply, that eager buyers are seeking out the closest thing to it. And it keeps the prices rising. In the 2020 Power 100, Leroy’s average price performance was 8.6%. Last year it was 39%, and this year it was a staggering 59.5%. The other estate associated with Leroy (but treated separately) is Domaine d’Auvernay. Although not in the top 10 (it slipped down the rankings this year due to low trade figures), it saw average price increases of 127.2%, and had the secondhighest average trade price behind Domaine de la Romanée-Conti.

This fever around the most sought-after Burgundies continues to disenfranchise all but the wealthiest collectors, who, in turn, continue to drive the expansion of the category.

BURGUNDY

Burgundy’s previous surge was in 2018- 2019. Prices then plateaued but took flight once more during the pandemic.

But they are doing so against the backdrop of a much broader market for Burgundy. It remains the fastest expanding region in the secondary market. In 2018, 829 Burgundy wines were traded. In 2022 there were 1,859.

One of the region’s peculiarities is the number of wines a single domaine can produce, and the addition of négociant labels only adds to this pool. In some cases it is these wines where recent price increases have been greatest.

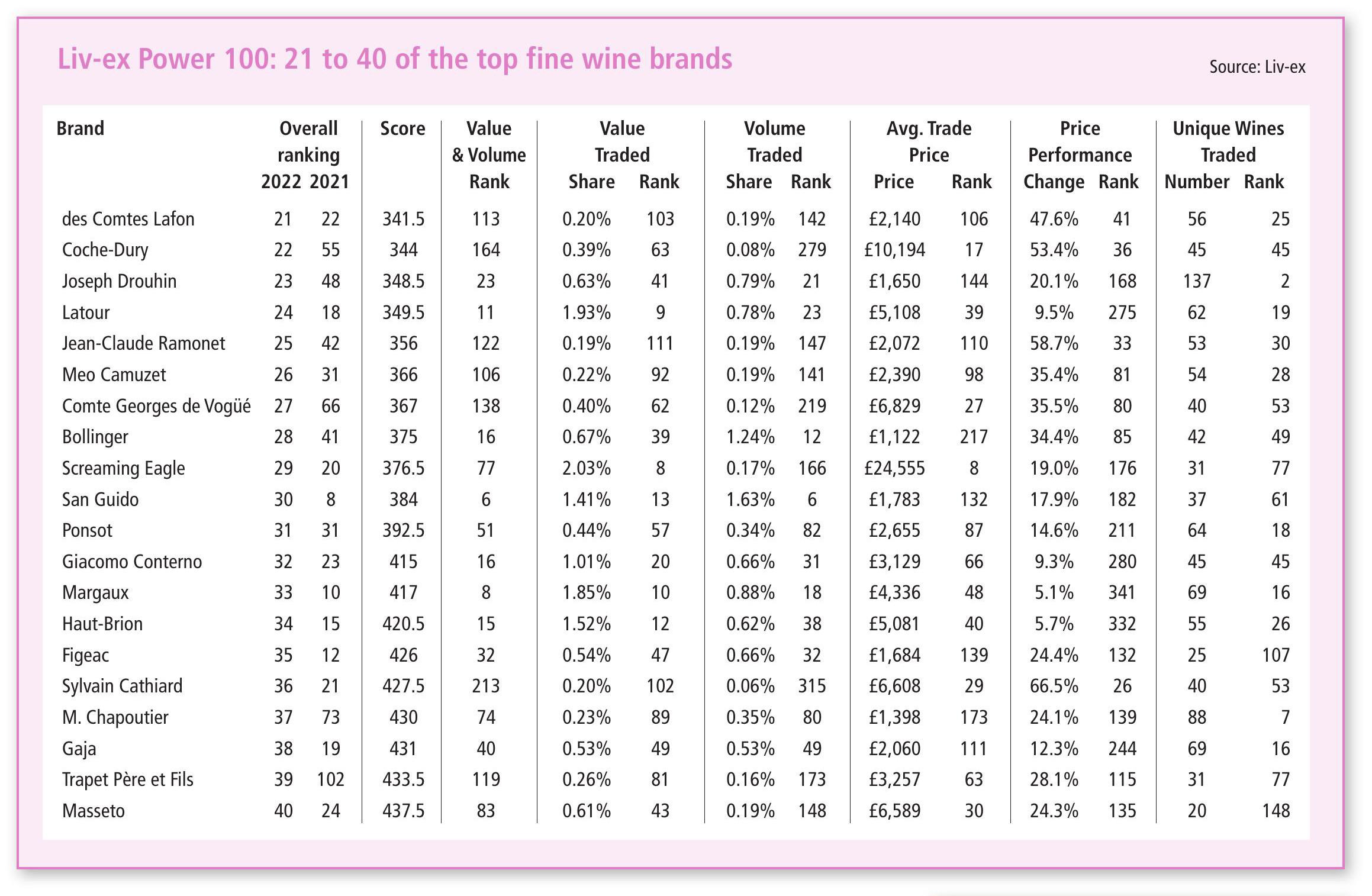

This has already been discussed in relation to Domaine Leroy, but it is also true of this year ’s second-most powerful label, Domaine Arnoux-Lachaux. The estate has been one of the region’s rising stars for a few years, but demand exploded in 2021-2022. Its average price performance was 487.2% but certain wines rose by more than 1,000%. Some of the biggest price rises were for the négociant label Charles Lachaux, which (like Leroy) offered an accessible point of entry to a rising brand, and have since hit new highs.

Conversely, trade for both Arnoux-Lachaux and Charles Lachaux has declined as 2022 has gone on, especially for the latter. It is possible that it is a brand that has already grown too hot for some to countenance buying.

This once again raises the question of Burgundy’s price sustainability. Speculation is undoubtedly an issue but ultimately, there is still not enough supply if demand continues to rise. Furthermore, the upcoming 2021 vintage release will yield hardly any fresh stocks. This will likely keep prices high, but some prices may not rise at quite the same speed.

CHAMPAGNE

Champagne has been a quiet presence in this year ’s Power 100, with just nine brands in the ranking. However, it is a growing force in the secondary market that has truly begun to break out; amassing high levels of trade, showing strong price performances, and with a growing number of brands qualifying for inclusion – even if they have not quite made it to the top just yet.

The standout brand has been Louis Roederer ’s Cristal, one of three Champagnes in the top 10. It has been the top-traded wine by volume, and third top-traded by value over the latest Power 100 year. It first entered the top 10 in the 2019 Power 100, and has not left it since. Dom Pérignon may have a stronger price performance, and Krug may have a higher average trade price, but measured by its sheer levels of trade, Cristal has become the standard bearer of Champagne’s secondary-market drive. Another cluster of brands worth keeping an eye on as the category evolves are some of the ‘grower ’ labels, such as Jacques Selosse. Selosse (which entered the Power 100 last year) jumped 25 places to 11 ththis year, because of strong price performance and a high average trade price. Egly-Ouriet is another smaller house that made it into the top 100 this year, up from 260 thlast year. And finally, although they missed making the top 100, the secondand third-best brands for price performance, trailing only Arnoux-Lachaux, were both Champagnes – Ulysse Collin, and Jérôme Prévost.

BORDEAUX

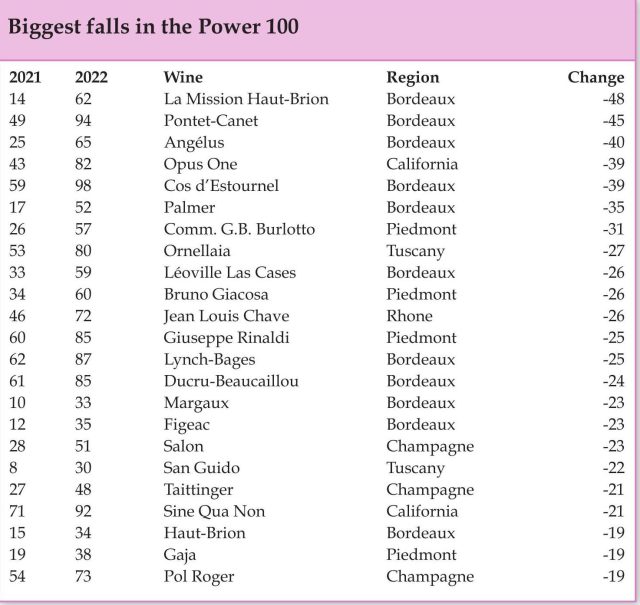

It would be easy to see the situation of Bordeaux’s brands as a negative one. The region’s total trade continues to shrink, the number of brands in the top 100 has fallen to a new low, and the highest-ranked brand (Château Mouton Rothschild) is in 13th position.

Compared with the price performances of other regions, Bordeaux looks weaker, despite its performance being above the average performances seen in pre-pandemic Power 100 rankings. Looking more closely, though, bright spots begin to appear. Château Lafite Rothschild is still the second-most traded brand by value, and one of the top 10 by volume.

Château Cheval Blanc only dropped one place, with a solid all-round performance, while Château d’Yquem rose by 20 places, with a sizeable number of vintages trading, and high trade value.

Anticipation of Château Figeac being promoted in the Saint-Émilion classification this September (which did indeed happen) made it one of Bordeaux’s best price performers, but it still dropped down the rankings. On the one hand, many other wines had much better price performances, but also Figeac’s trade value and volume fell as many buyers had stocked up the year before in anticipation of its promotion. Fumbled en primeur campaigns and stock retention are now long-standing issues for Bordeaux, which continue to hold its wines back in the secondary market. Nonetheless, few regions offer the concentration of brand power, prestige, availability, longevity and, increasingly, good value that Bordeaux does. Compared with the soaring prices of top-flight Burgundy, or even some prestige Champagne, good claret remains a solid proposition.

ITALY

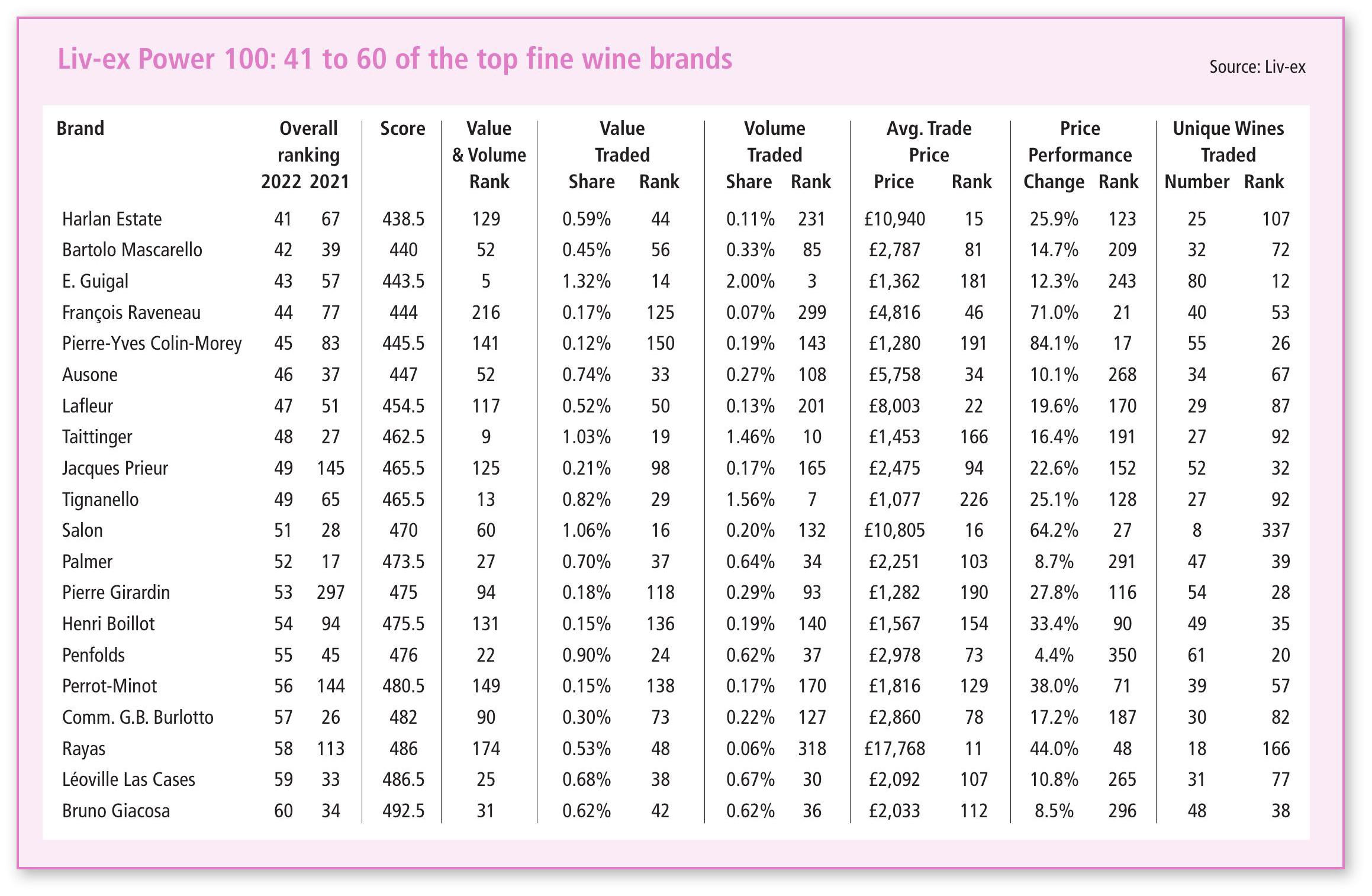

It was only two years ago that Italian trade seemed to be on an unstoppable rise. That tide has receded a little, however. The high US tariffs on European Union wines, from which Italy was excluded, were an important factor in its secondary-market success from 2019 to early 2021. Since those tariffs were abolished, trade for Italian wines has declined, from around 15% of trade in last year ’s report to 11% this year.

Many Italian wines have dropped down the list. A bit like Bordeaux, total trade by value and volume is still strong, but price performance has slowed, especially compared with Burgundy and Champagne. Sassicaia remains the highest-ranked Italian brand, and the sixth most-traded by volume, though it dropped by 22 places to 30th this year.

The Italian brand on the move, though, is Tignanello. It rose by 16 places to 49 ththrough a combination of high trade by volume (seventh overall) and thus a high total trade value. It also helps that it is the cheapest Italian wine in the top 100, with an average case price of £1,076.

CALIFORNIA AND THE RHÔNE

Much like Italy, with Burgundy’s dominant performance in the secondary market, there appears to have been less focus on California and the Rhône. On the other hand, both regions added brands to this year ’s top 100 – two from California, and one from the French region.

Despite the new additions, many of California’s leading labels slipped in the rankings this year, with Screaming Eagle falling by nine places. The high prices of top Napa Valley wines mean they score highly when it comes to trade by value and average case price. But they have fewer wines trading, volumes are low and, again compared with other regions, their price performance is not as high. Nonetheless, Harlan Estate climbed 26 places. Scarecrow and Hundred Acre both saw big jumps into the top 100 as well – both returning after a long hiatus.

Despite only having five wines in the top 100, the Rhône enjoyed success. While Jean-Louis Chave dropped 26 places, the other four brands from the region all rose.

These included Château Rayas, back into the top 100 with a jump of 55 places, thanks to a strong average trade price and price performance. The top-ranked Rhône label was Michel Chapoutier, which, like Guigal, can offer a multitude of different wines thanks to its hybrid estate-négociant business model.

CONCLUSION

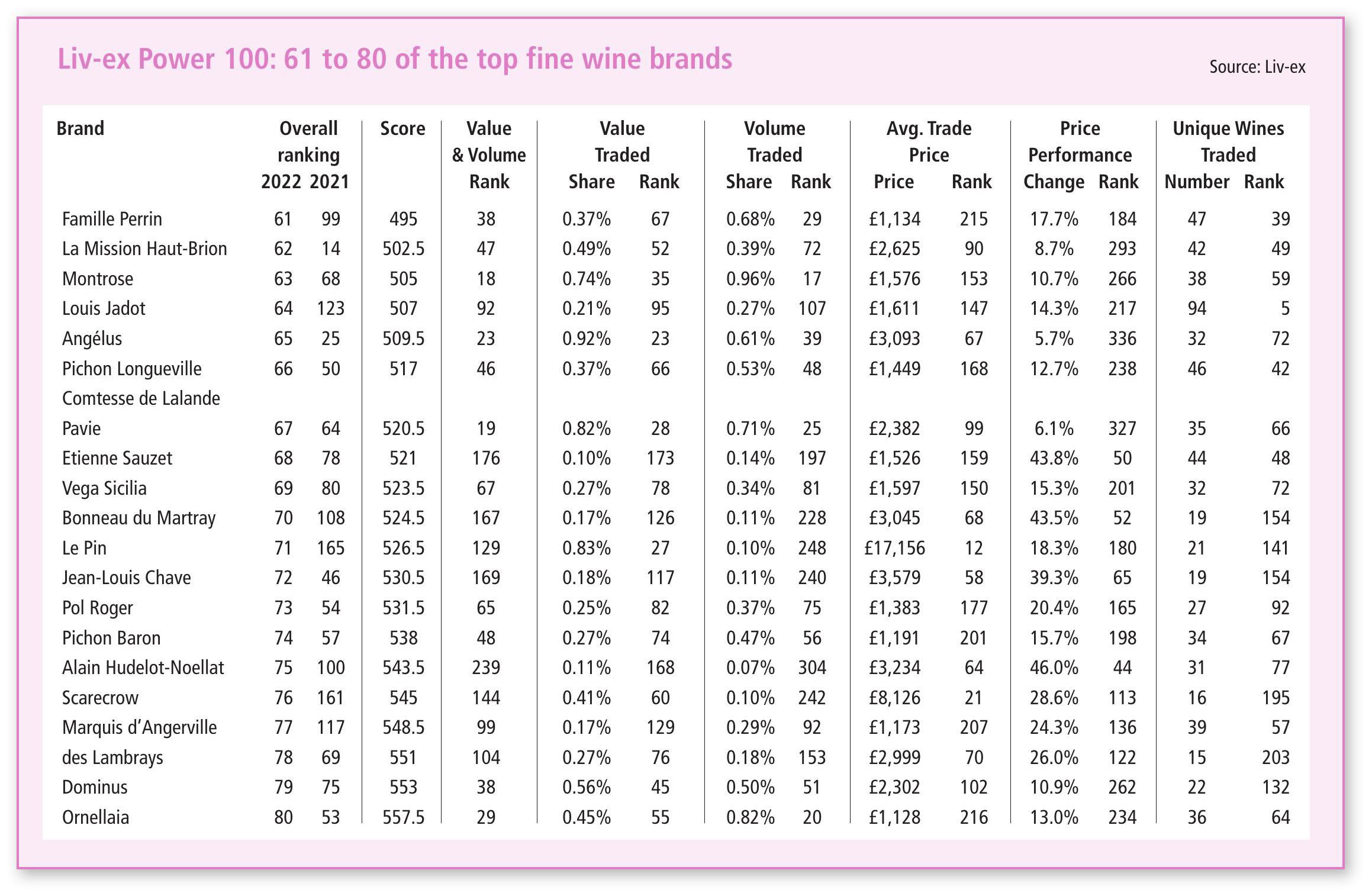

The Power 100 is a snapshot of the everchanging landscape of the secondary market. This year ’s list caught Burgundy at the very height of its latest upswing. Yet, already, the direction of the market in 2022 suggests change is on the way.

Just as we saw in 2019, Burgundy’s latest surge may be dizzying but could be swiftly stymied by a lack of supply, and an increasing reluctance to pay such steep prices for handfuls of bottles. The higher it flies, the thinner the air, and the fewer buyers there are.

Furthermore, as 2022 has gone on, the monthly performance of the Burgundy 150 index has sputtered. It ran flat in June and August, rose by 1.8% in September, and again by 0.7% in October – in each of those last two months it recorded its smallest monthly gains since August 2021.

The clear momentum is now with Champagne. Cristal and Dom Pérignon have been at the forefront of trade throughout the year. The Champagne 50 is the best performing Liv-ex Fine Wine 1000 index over one year, and is quickly closing in on the Burgundy 150 as the best-performer in the year to date.

The market has moved in a positive direction. As mentioned previously, all the brands in the top 100 saw their prices rise. But market headwinds are strong, and further price rises may not be as easy to come by. After some record years as the market expanded, the rate of growth, measured by the number of wines trading and qualifying for the Power 100, was not as great this year as it was last year.

Between 1 October 2021 and 30 September 2022, 12,332 wines were traded from 1,694 producers, respective increases of 4.2% and 1.6% on the same period a year earlier. The number of wines qualifying for inclusion was 422, a rise of just 0.3%.

Overall, the market continues to bring in new wines from around the world – Kumeu River from New Zealand, Chacra in Argentina, and Spain’s Telmo Rodriguez were among the new qualifiers this year – and the market remains broader and more balanced than it was a decade ago.

Nonetheless, looking forward to next year ’s Power 100, it is hard to shake the feeling that things are going to look quite different once again.

Feature findings

• Burgundy reigns supreme in this year ’s Power 100, with last year ’s bullish momentum rolling into this year and reflected in a continued broadening of wines traded and price rises.

• Champagne’s star continued to rise, with quality and value being the key drivers.

• For the first time ever there are no Bordeaux labels in the top 10.

• The price performance of Bordeaux was overshadowed by Burgundy and Champagne, but the First Growths held their own in terms of value traded.

• The Italian surge abated a little, but Tignanello put in a particularly stellar performance.

• All the brands in the top 100 have risen in price in what has been a blistering trading environment.

About Liv-ex

Liv-ex is the global marketplace for the wine trade. Along with a comprehensive database of real-time transaction prices, Liv-ex offers the wine trade smarter ways to do business. Liv-ex offers access to £80m worth of wine and the ability to trade with more than 600 other wine businesses worldwide. They also organise payment and delivery through their storage, transportation, and support services. Wine businesses can find out how to price, buy and sell wine smarter at liv-ex.com.

Related news

Zamora Company to distribute Bottega sparkling wines in Spain

Cabernet Franc on track to become the official grape variety of New York State