Just how green is pink?

As producers move to capitalise on two booming trends – rosé wine and clean living – it has given rise to a flurry of pink expressions that claim to be good for both us and nature. But, Elizabeth Gabay MW asks, how green really is Provence rosé?

WHEN CAMERON Diaz and Katherine Power launched Avaline, their “clean” wine range, their success indicated that consumers are interested in wines that claim to be good for their body. With a third of Provence producers registered as organic, biodynamic and sustainable, many Provence rosés could be described as “clean”, but, as Maud Negrel of Mas de Cadenet, which produces Avaline rosé, explains, she was contacted after “Cameron had tried to find a clean natural Provence rosé and could not find one, so decided to create one herself”, suggesting that some producers may be rather bad at marketing themselves.

But much more should be considered when labelling a wine “clean and natural”. Sustainability and a low carbon footprint should be high up on the list of concerns, of course. Rosé is often accused of high energy use, and with 90% of Provence wine being rosé, producers need to be conscious about sustainability in the cellar. Though it’s worth noting that energy used in the winemaking process is just as applicable to red, white and rosé in terms of viticultural machinery, cellar equipment, lighting and, most of all, in temperature control and bottling.

With 7.4 million hectares under vine globally in 2018, according to the Australian Wine Research Institute, 32% of CO2 emissions are thought to come from viticulture and vinification. Around 16m tonnes of CO2, and 68% of CO2 emissions come from glass bottle manufacture and transportation, bringing the footprint up to around 76m tonnes of CO2 produced by the winemaking trade.

In the EU, winery electricity consumption amounted to 1,750m kWh for the 2016 vintage, including France’s no-small contribution of 500m kWh. It doesn’t stop there. The South Australian Wine Industry Association estimates that refrigeration can use up to 50%-70% of a cellar’s electricity bill. The energy use for rosé is probably towards the upper end of this estimate. Air conditioning can use up to 10% of the electricity, lighting 10%, filters and wastewater 6%, air compressors 2% and crushers another 2%.

TEMPERATURE CONTROL

The cellar itself is a good way to reduce the cost of temperature control. Provence’s old agricultural history has resulted in many estates with big stone barns and, especially in the centre of the region, old silkworm farms (magnaneries) were built with thick stone walls and small windows high up under the roof, creating a cool ambient temperature, around 15°C, such as at Châteaux Mentone, St Martin, Gasqui, Ste Roseline, Vignelaure, Font du Broc and Chêne Bleu (Luberon).

From the 1930s onward, there was a growth in development in wine production, with a number of cellars made with thick walls, often built semi-underground. Domaine de Blanquefort has a 1930s cellar, embedded in the hillside, with the entrance facing north and concrete tanks in the coolest part of the building.

The drawback of these old cellars in places such as Provence is that they are not often easily adapted to modern winemaking. Gravity flow, logistics or size are not convenient, and a modern cellar needs to be constructed from scratch. Château de Selle (Domaines Ott) has built a new cellar with massive stone blocks and small windows, partially buried in the hillside like Châteaux Thuerry, La Coste, Bellini and Domaine de Sarrins, while Château Romanin has completely recreated a vaulted stone cellar underground.

If digging down is not possible due to bedrock or high water table, other measures can be taken. Château d’Esclans, for instance, is currently building vast new cellars, with fully insulated walls and ceiling, described by technical director Bertrand Léon as being “like a fridge”.

Grand Cros has built a cellar with small high windows that are opened at night to allow the hot air to be sucked up and out. Bastide de Blacailloux has a new cellar with thick cement walls, partially underground and, like Château Pesquié (Ventoux), planted with a green roof garden that doubles up as excellent insulation. Ensuring that a facility is insulated can greatly help to maintain temperatures and minimise energy costs.

Energy consumption is also seasonal, with the highest consumption usually in August, September and October, mostly required for chilling (50%-70% of electricity consumption). Grenache, the mainstay of Provence rosé, is highly prone to oxidation, and keeping the grapes and juice cold is regarded as being essential to preventing such oxidation.

Night harvesting is also used to bring in fruit as cool as possible. The pressing itself can be done with dry ice to keep the juice, rather than the grapes, cold. In fact, Tina Tari of Blanquefort feels it is more energy-efficient to chill the juice as it leaves the press on its way to the tank, while Richard Maby, who runs family estate Tavel, feels that the chain of keeping the grapes cool from harvest to tank reduces the need for extra chilling.

Temperatures of less than 10°C, help to delay the start of fermentation, and increase the speed of sedimentation, making for cleaner juice. The use of pectolytic enzymes allows a considerable reduction of settling times. The process of cold settling, led by research from the Rosé Research Centre is almost universally carried out in Provence. Alternatively, the flotation method, more commonly found in Australia and New Zealand, could be used where the must settles overnight, with no extra chilling.

Modern tanks include a range of systems, with newer versions having increased efficiency. Fibreglass fermentation vessels are less well insulated, while cement has good natural insulation.

Château d’Esclans uses an innovative method to control the temperature for Garrus’s fermentation in barrel, using computers to regulate daytime chilling to avoid excess energy use. In general, optimal fermentation temperatures are 25°C for red wines and from 18.3°C to 20°C for whites.

Temperatures are generally even lower for rosé, from around 12°C to 18°C, with the lower temperatures giving more bonbon anglais fruit. Tiziana Nardi, a researcher with the Council for Agricultural Research and Economics in Rome, has been working on fermentation at higher temperatures to reduce its carbon footprint. She has established that raising the fermentation by even a couple of degrees significantly reduces costs. Nardi says: “The use of cold in winemaking is an economic and an ecological problem.”

With the use of refrigeration firmly anchored in rosé winemaking, sourcing energy is important. Alexis Cornu, of Provence’s MDCV group, points out that France’s energy consumption has a strong focus on relatively cheap nuclear energy, reducing the impetus for alternative sources.

The Cooperative of Correns (a highly ecologically focused village, and where George Clooney’s grapes from his recently bought Domaine du Canadel are destined to go), has 1,000m2 of solar panels. Pesquié has enough solar panels to produce more energy than required, d’Esclans is installing solar panels in its new cellar to provide one third of its energy needs and, since 2012, Château de Lagarde has a 20ha field of solar panels, making it the first vineyard in France to have a positive energy account. Blanquefort is considering wind energy as an even more ecological option. Grand Cros, Château de Mille and Clos Gautier all use renewable energy. Highly efficient geothermal heat pumps are also being studied.

Although vinification does not produce large volumes of CO2 , it has been estimated that if the wine industry could work together, sequestration during fermentation could make wine a negative emission industry. Alcion Environnement, a subsidiary of Veolia, is working on capturing CO 2 during fermentation. Currently, harvested CO2 can be transformed into other carbon-based materials, such as biofuel, or sent underground to remineralise. Nicole Rolet at Chêne Bleu has installed a system to capture CO2 , creating fertiliser pellets to enrich poor soils using a system developed by Sheffield’s Institute for Sustainable Food.

It has been estimated that from 9.6cl to 12.7cl of water is required per 75cl wine bottle, with wastewater produced being responsible for about 98% of this. Reusing water is still very low in France compared with many other countries. Château Galoupet uses reservoirs to collect rainwater, Château de Mille has a wastewater-treatment facility, while Chêne Bleu has planted a bamboo forest around a basin into which grey water flows. The bamboo sucks up the impurities and leaves pure water, which is then reused.

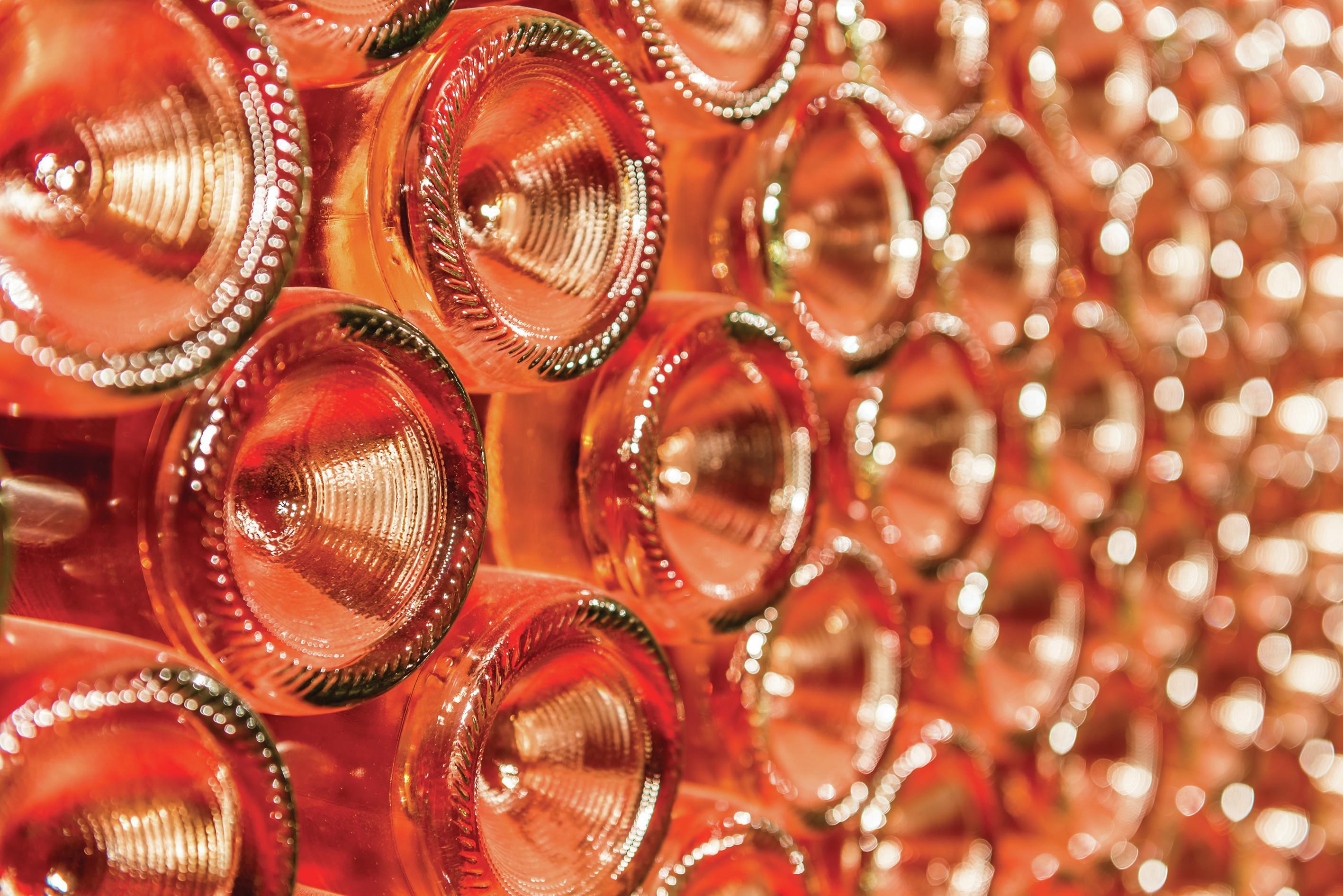

BOXING CLEVER

Packaging is a major use of energy, an important point in Provence, where the presentation of rosés is a key part of marketing. Lighter glass bottles can be an unnoticeable way to reduce the carbon footprint. The bottles specified by the syndicat for the appellation for Tavel and Lirac have moved to lightweight versions. Four years ago Château de Berne changed its iconic square bottle to a lighter version and no one noticed. Philippe Bru of Vignelaure uses lightweight Bordeaux bottles, but notes that heavier ones are often used by négociants for premium rosés.

Using recycled glass, which is less clear than new, is regarded as less attractive and detracts from the colour of the rosé.

“Clear (non-recycled) glass indeed showcases the colour of the wine in the bottle. However, clear glass presents what we consider to be two contradictions to our aim of crafting wine with the highest respect for our environment, and the quality of the wine itself,” says Jessica Julmy, managing director of Château Galoupet, a new Moët Hennessey-owned rosé producer in Provence.

“The first is that it is made of 100% sand, not from recycled glass. This uses more energy and produces more CO2. The second challenge is the impact on our wine, as we have crafted an expression that is rather pale, with low Anthocyanin concentration, and which can be kept over time so we’ve looked at solutions that will also protect the quality.”

In May, Château Galoupet will reveal two new unique formats for its pink wine, the result of two years of R&D, the details of which are being kept under wraps.

Eliminating the use of new glass bottles would reduce producers’ bottling emissions by 65%. Aluminium cans are even better, as are bag-in-box wines, and best of all are ocean-friendly PolyEthylene Terephthalate (PET) bottles, but consumers do not like plastic, and producers struggle to sell bag-in-boxes.

There is some discussion about introducing a bottle-deposit scheme in France by 2025, although there is concern among Provençal winemakers that this will be difficult to introduce.

According to a 2009 study, reusing bottles reduces water consumption by 33%, energy by 76% and greenhouse gas emissions by 79%.

CARBON FOOTPRINT

Encirc, part of the Vidrala group, is trialing producing glass bottles using only energy from biofuels, reducing the carbon footprint by up to 90%. Transport, especially for heavy bottles, also uses energy. Domaine de la Courtade, on the island of Porquerolles, one of the three Îles d’Hyères off the coast of Provence, ships wine in bulk to the mainland for bottling and storage to reduce its carbon footprint.

Plastic-backed wine labels, designed to prevent labels coming off in ice buckets, and plastic-coated corks are also issues. Sea Change bottles a range of wines with minimal environmental impact including sustainable paper labels and uncoated cork. Its Provence rosé comes from Domaine Pigoudet.

Extensive cork oak forests are also being planted in Provence with the aim of providing all local corks by 2070.

As Matthieu Negrel of Mas de Cadanet says, most rosés do not achieve a high enough price to encourage investment in carbon-neutral equipment. There is still work to be done in creating a carbon neutral, fully ‘clean’ rosé, but there is plenty of discussion on the subject.

Feature findings

•A third of Provence producers are registered as organic, biodynamic and sustainable.

• Rosé is often accused of having high energy use.

• In the EU, winery electricity consumption amounted to 1,750 million kWh for the 2016 vintage, including France’s 500m kWh.

• Many wineries have old cellars made with thick walls, often semiunderground, with one drawback being that these are not often easily adapted to modern winemaking. Gravity flow, logistics or size are not convenient, and a modern cellar needs to be completely constructed.

• Using recycled glass, which is less clear than new, is regarded as being less attractive and detracts from the colour of the rosé.

Related news

The highlights of the hors Bordeaux 2026 Spring collection

Santiago Marone Cinzano: 'my generation wants wines that are ready to drink'

Raise a glass to Cabernet excellence: enter The Global Cabernet Sauvignon Masters 2026