In focus: The heroic rise of the Super Tuscans

Fifty years on from the launch of Sassicaia, Richard Woodard explores what the term ‘Super Tuscan’ means in 2021, and asks whether it remains fit for purpose.

It’s 50 years since the first commercial release of a rather idiosyncratic wine from an estate located near the Tuscan coast, and close to the small settlement of Bolgheri.

The origins of Sassicaia, like those of the Super Tuscan movement in general, have an almost mythical air about them: from the planting of Bordeaux grape varieties in the stony soils of Tenuta San Guido by racehorse breeder and Graves nut Marchese Mario Incisa della Rochetta in the 1930s – to the release of that 1968 vintage at the behest of his son, Nicolò, and nephew, Piero Antinori.

Five decades on, the Super Tuscans have gone on to spearhead the global rise of Italian fine wine, despite the lack of formal classifications or precise definitions. So, what does ‘Super Tuscan’ mean in 2021? And does the term remain fit for purpose?

Answering the first question is made more difficult by the evolution of Tuscan winemaking since the early 1970s, much of it prompted by the success of the Super Tuscan wines that followed in Sassicaia’s wake – and by the understandable desire of more recent ventures to earn the ‘Super’ sobriquet for themselves.

“We generally see Super Tuscans as being Tuscan wines where the grape varieties do not correspond to DOCG regulations, but rather have more of an ‘international’ grape and blended element,” says Matthew O’Connell, head of investment at Bordeaux Index.

“But this of course has extended, such that style now has some additional relevance – ie names like Sassicaia, Ornellaia, etc, have clearly pushed far through the ‘Bordeaux-like’ category and defined a style of their own.”

Where once these wines stood on the shoulders of Bordeaux through their adoption of non-Tuscan grape varieties, now they stand alone entirely on their own merits.

So, while Wine Lister COO, Chloe Ashton, references ‘international grape varieties’ as a defining aspect of Super Tuscans, for her “the pseudonym is brand-driven, with the obvious requirement of exceedingly high-quality wine”.

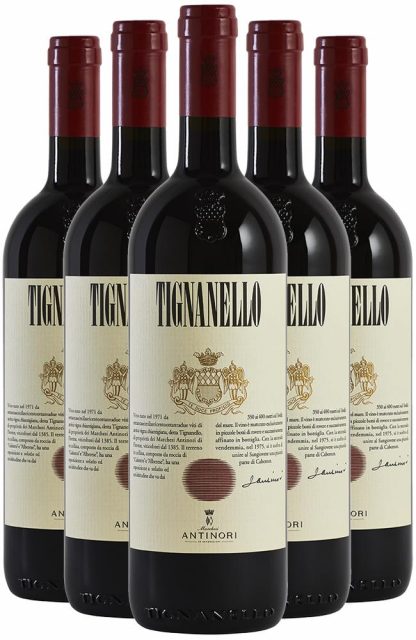

She adds: “For me, it mirrors an unofficial, simplified and demand-led version of the Bordeaux Left Bank classification – the godfathers of Super Tuscan winemaking (Sassicaia, Ornellaia, Masseto, Solaia, Tignanello) now have a 20-40-year lead on many of the more recently established ones, so they will always be collectors’ first ports of call.”

Liv-ex data tends to confirm this theory, with all-time trade (2002-21) placing that hallowed quintet (Sassicaia, Masseto, Ornellaia, Tignanello, Solaia) firmly at the top of trading for Tuscan wines.

But focus on the past couple of years and the picture begins to shift slightly. In 2020, the top Tuscan wines were Sassicaia, then Ornellaia, Masseto, Tignanello and Soldera Casse Basse. In 2021 YTD (to July), they were Sassicaia, Masseto, Soldera Casse Basse, Ornellaia and Tignanello (Solaia sits in sixth spot, followed by Bibi Graetz ‘Colore’ and Redigaffi).

Partner Content

“Given the reputation of the trailblazers, new claimants might use the Super Tuscan title, but it often feels ‘name adjacent’ – a shorthand for a blend that uses non-Italian varieties,” says Liv-ex managing editor Rupert Millar. He cites the example of Soldera Casse Basse – a wine that has surged ahead as an IGT after splitting from the Montalcino DO in 2006.

“It was the fifth top-traded Tuscan wine by value last year and the third top-traded so far this year. Young or old, therefore, it doesn’t take Super Tuscan status (real or perceived) to find market success,” says Millar.

And is it better to achieve that standing among collectors on your own merits, rather than trying to shoulder your way into the Super Tuscan club? There are numerous Tuscan wines that are occasionally given that status – Ashton lists Tua Rita, Castello dei Rampolla, Siepi from Castello di Fonterutoli, among others, but labels them as “the best second options” versus that top five.

Nonetheless, O’Connell sees potential for further developments among this second ranking. “Producers who have clearly got one foot into the top category are – for me – Fontodi (eg Flaccianello) and Castello di Ama (eg L’Apparita),” he says.

“The quality is beyond doubt, as scores show, and, despite prices having gone up already, we think there could be higher price and activity levels in those names to come.”

As these comments suggest, ‘Super Tuscan’ – a term that was always vague at best – has, if anything, expanded its scope even further over the years. “It’s not a name that can be strictly defined by either winemaking method, varieties used or even internal Tuscan geography,” points out Millar.

“Many Super Tuscans are found on the coast in Maremma or Bolgheri, yes, but also inland. And, while some use 100% international varieties, others use Cabernet/Merlot to bolster an otherwise Sangiovese-led wine.”

Does this evolution make the term ‘Super Tuscan’ all but irrelevant today? Not really – because, although there are no formal rules or classification, that doesn’t stop collectors from understanding what it embodies.

“One could debate, for example, the Tuscan coast vs blended Chianti distinction, which is very relevant,” says O’Connell, “but for the most part the term has an international market understanding which means it remains fit for purpose.”

And it has a broader significance for Italy as a whole, adds Millar. “One might see the coming of the Super Tuscans as marking a wind change in Italian winemaking.

And the introduction of new grape varieties, different techniques and new technologies has benefited native Italian grapes enormously too – prompting change to see how they can be better cultivated and vinified – which has helped make Italy the exciting, diverse and flourishing wine country it is today.”

Related news

Maltby & Greek launches first own-label range

Majestic celebrates 'stellar' Christmas

Pop the cork on Prosecco glory: enter The Prosecco Masters 2026