The coca wine fad: a brief history

Author Ralph Hancock brings db readers a brief history of coca wine, a Bordeaux and cocaine combination that was imbibed with gusto by presidents as well as popes, and has been recreated by a descendent of the founder.

As soon as Europeans reached Peru in the 16th century they observed the stimulating effect of chewing coca leaves. This was made widely known by Charles Kingsley’s best-selling adventure novel Westward Ho!, published in 1855 and set in the Elizabethan era, where he writes of ‘that miraculous herb, which would … make food unnecessary, and enable their panting lungs to endure that keen mountain air’.

The Italian scientist Paulo Mantegazza experimented with coca in 1859, and wrote a paper enthusiastically recommending it: ‘I would rather have a life span of ten years with coca than one of 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 centuries without coca.’

His words were not lost on Angelo Mariani, a chemist from Corsica, who set about developing a marketable version of the miraculous herb. Europeans could hardly be expected to chew leaves, especially as it was necessary to add lime to extract the drug from them. He devised a mixture of coca and Bordeaux wine, fortified with brandy and sweetened. The alcohol extracted cocaine from the leaves and made it easy for the body to absorb. Mariani launched it on the market in 1863. A small glass, 100 ml, of this wine contained the equivalent of 21 mg of cocaine, so it packed quite a punch.

The drink, sold as Vin tonique Mariani à la Coca de Pérou, or Vin Mariani for short, soon achieved considerable success. Unlike most of the rubbishy remedies of the time it delivered real effects, stimulating and overcoming exhaustion. Recommendations from famous people – no doubt diligently fished for – came in, among them American president Ulyssses S. Grant, novelist Émile Zola, composers Charles Gounod and John Philip Sousa, inventor Thomas Edison – and, most notably, two popes, Leo XIII and later Pius X. The first of these went as far as to award a Vatican gold medal to Mariani, and allowed (or at least did not forbid) his face to appear in advertisements for Vin Mariani.

Imitations soon appeared, mostly containing more coca than the original. Mariani countered this with a stronger export version of the wine containing 25 mg of cocaine per 100 ml glass.

One of these copies was developed by Colonel John Pemberton, who had been wounded in the American Civil War and, after medical treatment with morphine, had become addicted to it. His original intention was to make a ‘brain tonic’ which would overcome the addiction and be a general stimulant. In 1885, in Columbus, Georgia, he launched Pemberton’s French Wine Coca, which in addition to coca contained an extract of African kola nuts, a potent source of caffeine.

Partner Content

He was soon overtaken by events when some local authorities in Georgia prohibited the sale of alcoholic drinks – a movement that anticipated the United States’ complete Prohibition of 1920. Pemberton therefore produced a non-alcoholic version of his tonic, which he called Coca-Cola. Unlike the wine, which was sold in bottles, Coca-Cola was distributed as a syrup for use in drugstore soda fountains. It was not bottled till 1894.

The original formula of Coca-Cola included 5 ounces of coca leaf per gallon of syrup, a hefty dose. In the face of growing public disapproval of cocaine, this was reduced by 90% in 1891. Today the drink is made with coca leaf treated to remove the cocaine, though it remains high in caffeine.

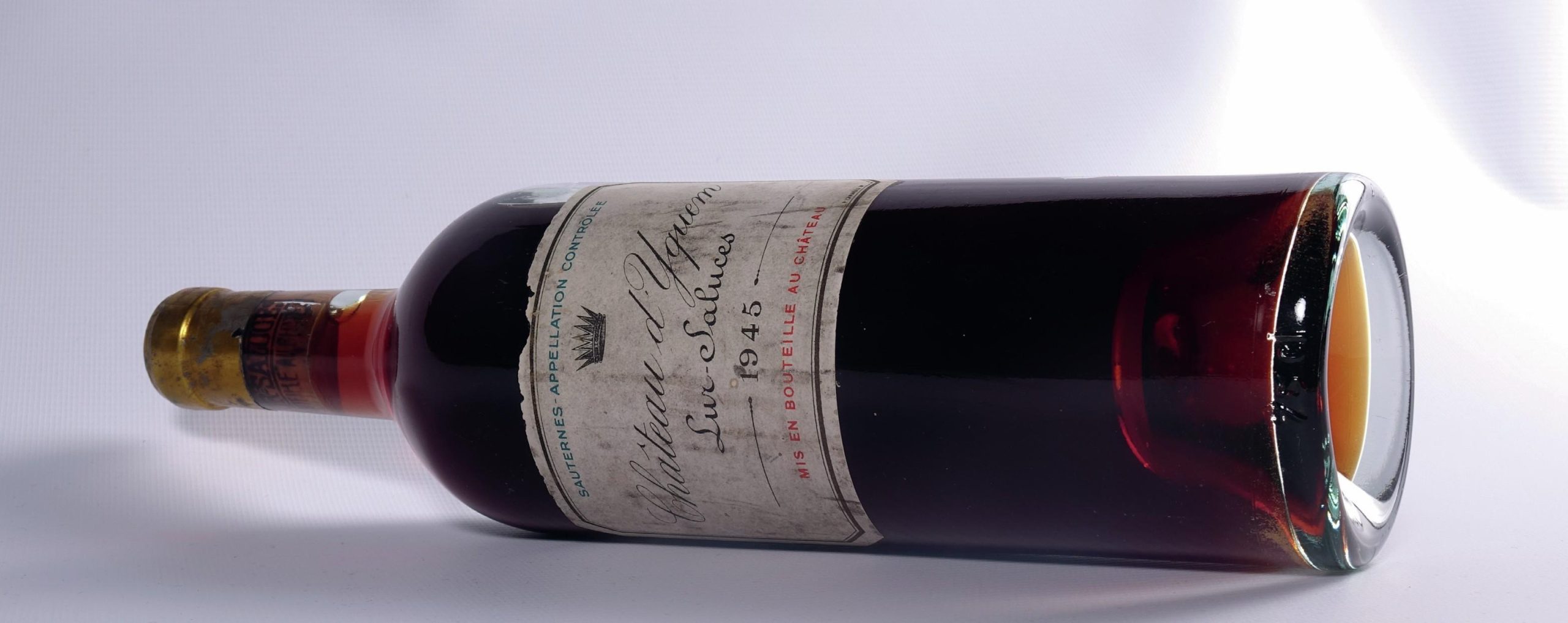

Increasing legislation against cocaine eventually caught up with the original Vin Mariani, and production ceased after the death of Angelo Mariani in 1914, when the formula was also lost. But in 2014 a probable descendant, Christophe Mariani, developed a version of the wine recreated by analysis of original samples, and it was released on the market by Babco Europe in 2017. Like the original it is based on Bordeaux, fortified to 22° and sweetened, but to comply with current legislation it uses decocainised coca leaf – which, some might say, misses the point of the original potent brew happily swigged by popes.

This brief history is nearly as enjoyable as a shot of Ambrecht’s Coca Wine. As Ambrecht’s says, “in large quantities,” this stuff produces “an indescribable feeling of satisfaction.” The illustrations are some of the best quality, most readable ones I’ve seen, and include some lesser-known brands I’d not seen before. Your article proves that reading about coca can be almost as good as (and probably preferable to) consuming coca.

Today VIN TONIQUE MARIANI is made from Corsican White Wine and Bolivian Coca leaf extract.

The TONIC WINE of Coca Mariani reproduced with its original 50 CL container, contains 16% VOL

(c) the official website

The bottle of the revived wine in the last illustration, whose label states ‘Bordeaux’ and ’22°’, is from a small batch produced before the wine went into full production. Evidently they have reduced the strength and changed to a different wine for the present version.