Strange Tales: Gunpowder and ‘the urine of a wine drinking man’

Gunpowder radically changed the medieval world, battering down castle walls, ushering in the age of the gun and eventually the end of knights. But to make gunpowder’s crucial ingredient, saltpetre, there was a component that only wine drinkers could (apparently) provide.

Gunpowder, as is widely known, was invented by the Chinese in the 9th century AD and then spread westwards, appearing in the Muslim lands of the Middle East by the mid to late 13th century and Europe in the early 14th century.

Our first mention of gunpowder weapons in Medieval Europe is from Florence in 1326 when small firearms were ordered by the city fathers for the defence of the walls.

From there, their use proliferated with revolutionary consequences for warfare on the continent. There is an argument that in every quarter of a century between the 1320s and 1450s there was more and more rapid development in the use of gunpowder weaponry than in the entirety of the following three centuries.

Although their impact on battlefields would take a little longer to become truly effective[1], the use of cannons – known variously as ‘culverins’, ‘serpentines’ and ‘bombards’ according to their size – transformed the most common form of medieval warfare, sieges.

Cannons could batter previously stout walls to pieces in days or even hours. The Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453 with the help of several cannon not least an enormous bombard called ‘Basilica’ which could reputedly throw a 600lb (272kg) stone ball over a mile.

Marvellous as generals no doubt found cannons, their use was hindered by the very thing that made them so effective, which was gunpowder.

Until this point, artillery had required torsion, weights or just plain old human muscle to hurl a projectile its required distance but cannons needed a propellant.

Gunpowder – or black powder – is a blend of three chemical elements: sulphur, charcoal and potassium nitrate, also known as saltpetre. These are mixed in proportions of 75% saltpetre, 15% charcoal and 10% sulphur.

Sulphur and charcoal were accessible to medieval gunpowder makers but saltpetre, the biggest element, was rather trickier to source. Some was available through trade but it was hugely expensive.

By the 1380s, however, medieval gunsmiths found that a mixture of earth, urine, dung and lime were capable of producing the desired (if smelly) results.

Urine in particular is the key to producing saltpetre because it provides the ammonia which oxygen and bacteria turn into nitrates – a mix of magnesium, calcium and potassium, the former two you don’t want as they’re very hygroscopic so your powder will get wet very easily.

By combining decomposing matter with urine and oxygen, early gunpowder makers were, unwittingly, replicating what happens in soil to produce the nitrates that plants need to grow. In the absence of plants, nitrate crystals form instead which can then be collected.

The Syrian scientist Hassan Al-Rammah explained in a treatise of 1270 that saltpetre could be obtained by dissolving the nitrate crystals in water and mixing in wood ash, which as it happens contains a lot of potassium carbonate. The potassium ions replace the calcium and magnesium and leave you with potassium nitrate.

Interestingly, although urine from any person or animal will suffice, several saltpetre recipes specifically recommended using urine from “a wine drinking man”, which was no doubt easy to find in Italy and Spain which were the centres of medieval powder manufacturing.

This might be one of the more hocus-pocus elements of medieval alchemy but urine from the previous night’s bender can smell pretty strongly of ammonia and it may be that it has higher trace elements that haven’t yet been processed by the liver.

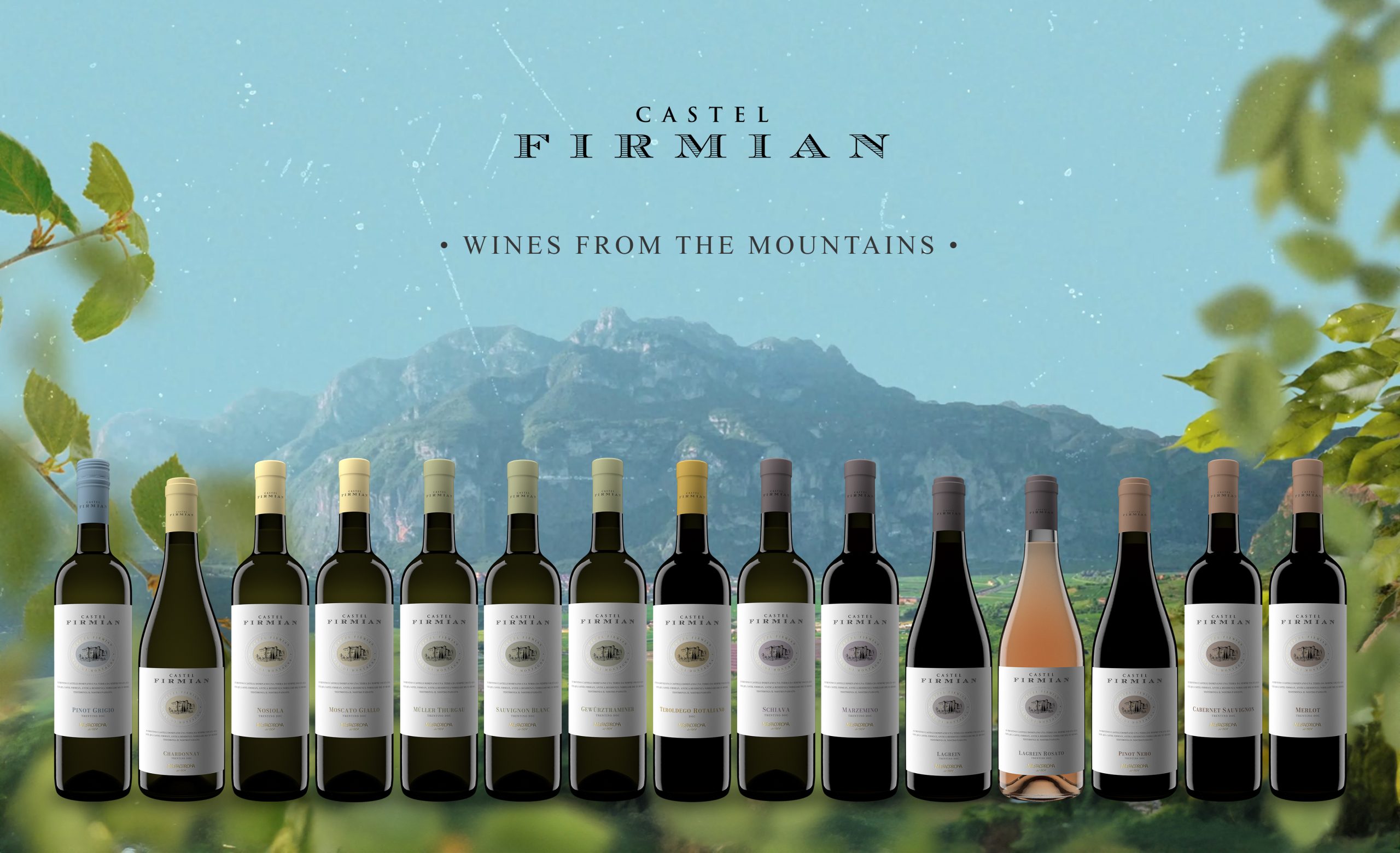

Partner Content

What actual effect this had on making saltpetre is hard to say, perhaps it might help speed up the formation of crystals or promote larger ones. The medieval mind certainly believed it more efficacious.

And alcohol became important in the mixing of gunpowder itself as well. To begin with, having mixed the requisite amounts of charcoal, sulphur and saltpetre together, they were ground into a fine powder called ‘serpentine’.

But very often this led to the ingredients separating afterwards when subjected to the vibrations of transportation aboard carts or becoming too compacted, both of which led to an uneven burn reducing the explosive potential.

By the late 14th and early 15th centuries, gunpowder makers learned that mixing the ingredients with liquid caused them to bind together better and had the benefit of being safer as there was less powder dust floating around in an era of lots of open flame.

So vinegar, distilled spirits, wine and, once again, “urine from a wine drinking man” (medieval people really put urine to a lot of uses) were used to create a paste which could then be dried, broken up and then sieved into different grains of powder the largest of which was the size of an ear of corn (wheat) hence it was called ‘corned powder’.

One can certainly imagine medieval powder makers making a case to their employer that extra wine rations were necessary in order to make tip-top gunpowder and any defects could be explained away by the quality of the rations they received.

So drink seems to have played its part in the creation of early gunpowder but there is one more link between alcohol and gunpowder worth recalling and that’s the origins of ‘Gunpowder Proof’ spirits.

The term goes back to the 16th century when distilled spirits were becoming popular as a drink rather than the sole preserve of physicians and alchemists for use in their concoctions and such.

As ever, the government quickly moved to tax spirits with the rate dependant on their strength. To test the alcoholic level, it is said, a pellet of gunpowder (no doubt a larger ‘corn’) would be soaked in the spirit and set light to.

If the gunpowder still ignited then that meant the spirit was ‘over-proof’ (57% or higher today) and therefore in the higher tax band.

This method was discontinued in Great Britain in 1816 in favour of the specific gravity test and the term ‘proof’, though still in use in the US, was replaced by ABV as the standard measure of alcoholic content in 1980.

But – maybe – that’s a story for another time.

[1] Though there is evidence Edward III employed some small cannons to unclear effect at Crécy in 1346.