Unfinished Business

Radical tax cuts on alcoholic drinks have curbed cross-border shopping between Finland and its Baltic neighbours. Domestic spirit sales have gone through the roof while New World wines re gaining share, says Penny Boothman

THE FINNS have always had something of a love/hate relationship with alcohol. Finland was in fact subject to a Prohibition Act in 1919, which was eventually repealed in 1932 when an exclusive monopoly on the import, export, manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages was granted and Alko opened its doors.

The monopolies on production, wholesale, export and import were later dissolved in preparation for joining the EU in 1995, but the retail monopoly was allowed to remain. Today, Alko is the sole retail outlet open to the Finnish public for alcoholic beverages over 4.7% abv.

Binge drinking may be a relatively new phenomenon in the UK but a Finnish campaign was started in 1959 to steer consumers away from the culture of drinking just to get drunk. Wine prices were substantially reduced while spirits prices were increased.

However, consumption continued to rise and in 1977 the government took a yet tougher stance and the advertising of all alcoholic beverages was banned. Spirits advertising is still prohibited – Alko can’t even list them on its website – but advertising wine, beer and cider is now permitted as long as it does not actually promote drinking.

So are there anylessons to be learnt in the UK from the Finnish experience. The Finns like a drink, whether it’s promoted or not. "Up until the end of 2003 we were seeing a very healthy growth level, we were at one stage the fastest growing [per capita] wine market in the world – we actually overtook Ireland!" says Katja Angervo, purchasing manager for wines at Alko Inc.

"I started in Alko a little over three years ago when wine had been on a continuous growth trend, and spirits consumption was basically stable," she continues. "That’s one of the issues which was a major point of concern when we came down in taxation.

Wine consumption had grown by 8.3% [MAT to end 2003], but in our latest figures for 2004, wine consumption is now down by 2.7%. In January, February and March 2004, wine was still growing but then after the taxation changes, which are more favourable towards spirits, we saw he consumption change to being more spirits oriented."

The taxes on alcoholic drinks were changed in March 2004, at the same time as the neighbouring – and significantly lower taxed – Baltic states joined the European Union, and restrictions on the volume of alcohol that Finns could bring home were eliminated.

"There were limitations on how much you could bring over, then it became that you were allowed to bring as much as you could prove was for your own consumption. That was a major change,"comments Angervo.

Spirited performance

Duty on spirits was slashed by 44%, while rates on beer came down 32% and wine by 10%, which has predictably led to a dramatic rise in spirits sales in Finland. In the week following the taxreduction Alko saw sales of hard liquor leap 72%.

"Taxation issues have nothing to do with the monopoly. We have no say in whether or not the taxation will change but certainly, in my opinion, they made the right decision in lowering the taxation on spirits so dramatically because this certainly would have led to a much bigger problem with cross-border trading," says Angervo.

"Cross-border trading is still an issue in which spirits are involved to some extent, but it now has most effect on beer, and the least on wine. Strong spirits are up 21.2% against last year, so that’s litres.

22% on a large base is a lot of liquid! You also have to keep in mind that we had the lower months of January, February and March before the tax reduction where spirits consumption was very stable, only growing by about 1.3%.

And then after March we had some phenomenal figures in the first month, but now it’s becoming a little bit more normalised. If we look at December figures for vodka, they were 18% higher than the previous year, but then when you look at wine figures, grape wines were only 1.8% higher than for the previous December."

So spirits are levelling off, albeit at a much higher level, while wine sales are worryingly static. For a government so concerned about excessive consumption and public health, these results seem a little bit less than favourable.

So, are further tax cuts likely to redress the balance? "I don’t foresee that in the very near future," says Angervo. "I do think it’s a slight shame that the taxation cut on wine was so low, but then looking at it from a member of parliament’s view I suppose it was a wise decision in that sense because there is very little cross-border trading on wine, so the consumers who are drinking wine would be buying it in Finland anyway."

In fact, Alko’s pricing policy makes buying wine in Finland a very attractive proposition. "We have very competitive pricing, on an international scale. Our expensive products like Bordeaux en primeurs, or wines that are on the Wine Spectator top rating list, retail at a lot lower in Finland because we have basically the same margin for all our differently priced products," Angervo explains.

"It’s a fixed margin, so it’s more favourable towards the wine connoisseur. No matter what price we purchase a product at, it will always retail at a fixed margin. We are not flexible in deciding the price points for the products.

It’s actually the producer, the importer or the agent who decides what price they sell the product to us at, which fixes the retail price." And, in the spirit of being fair to all, this information is freely available to producers.

"Everything about our pricing is open, so basically if you’re a producer in any part the world you can look on our website and calculate what price your product will retail at," she explains.

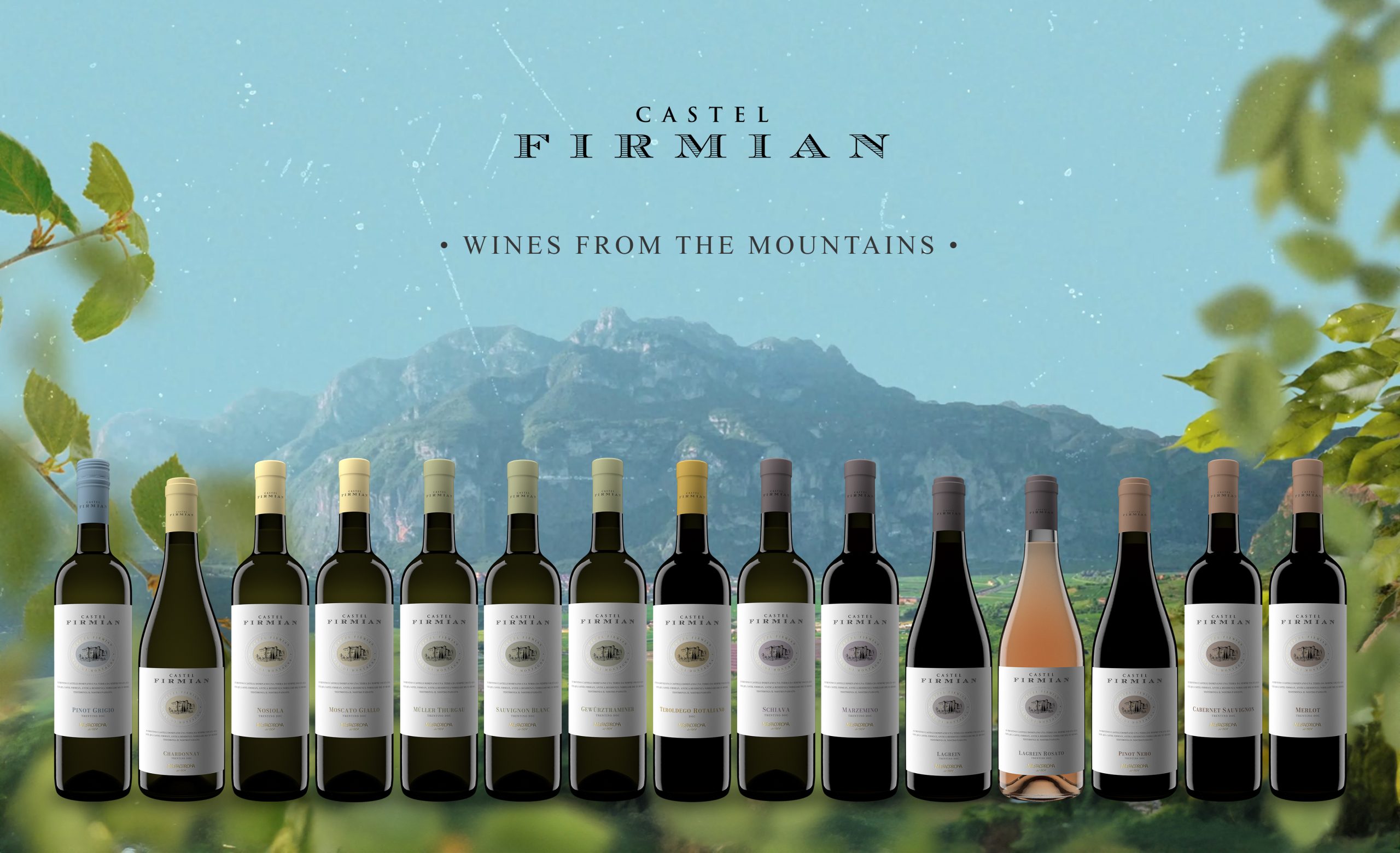

Partner Content

Public service

This is the mainstay of the original philosophy behind the monopoly. "I’m only interested in ensuring that the consumer gets the product for the least expensive price and from a reputable, reliable supplier," says Angervo.

A small number of independent wine importers now operate alongside the monopoly, servicing the on-trade and the monopoly itself. "We have very few importers in Finland. They have their portfolio of products, and if you are a small winery from the United States and you go knocking on the doors of the 10 largest importers they already have representation of larger US companies and they will say ‘No thank you, we have an agreement with Constellation, or with the Wine Group,’ or whoever.

So you can keep on knocking on the doors but because the business is still so small here there is not much choice. "So we offer the producer a means of getting their product onto the market without having an importer.

But what we do not do is promote the product in any way – it’s just one wine among the ,200 other wines on our shelves." The nature of a retail monopoly means that it has to be fair to all products, so Alko cannot advertise any specific lines.

But this doesn’t mean that producers can’t promote themselves. "The situation today is so tough that we would prefer it if there is somebody managing the product [in Finland], but it depends on whether the product is so well recognised already that it doesn’t need promotion," Angervo explains.

"The majority of the products that we import into Finland directly through Alko Logistics are more expensive, boutique-produced products." However, as in wine markets all over the world, there seems to be a consumer trend towards the lower price points.

"It’s actually a continuing issue. I mean it’s the same in the UK, of course. There’s a certain amount of money that a consumer is prepared to pay for a drink." However, slightly unusually, bag-in-box sales are not as strong as in the other Nordic countries and make up about 25% of wine sales, a figure that is closer to 50% in Norway.

New World challenge Whatever the price of the wines and however they get to the shelves, the New World is taking the wine category by storm. "Three years ago Spain had 42% market share on red wines and today they have 22%.

Chile has overtaken Spain so the big winners in the red wine sector are the New World countries like Chile, South Africa and Australia," says Angervo. "But it depends on whether you are looking purely at percentage growth or if you’re looking at litres, because Spain is still the second most popular red wine consumed by the Finns.

Australia only has 5.9% of the market share, even though it has almost 80% growth. It’s the same with white wine. South Africa is the leader right now in terms of volume and almost in terms of growth rate, it has 22% market share and it’s growing at 7%."

A survey published at the time of the tax cuts last year found that 56% of Finns were in favour of the changes but, perhaps surprisingly, more than 40% felt that the prices were now too low.

Angervo believes that the Finns are content with the monopoly situation: the choice of over 1,800 products is more than adequate; EU regulations allow those who want to extend their range to import from other countries, and the on-trade offers an extensive and sophisticated alternative selection.

Mail order is also permitted as long as consumers pay the proper taxes, but this isn’t common. "We have 320 Alko shops all around Finland and we are only 5.2 million people. We also have a lot of order places where you can go to the local post office or pharmacy or somewhere like that and you can actually pick up your alcohol from those spots.

So I think the consumers are very used to the system, and even though most people are very familiar with computers and the internet here in Finland, somehow mail order is not that popular," says Angervo.

One benefit the consumer enjoys when buying from a monopoly, rather than taking a chance with mail order, is the level of guidance available. "We are a speciality retail chain and you can’t compare us to Tesco or anything like that because we deal purely with alcohol.

So all the staff who work in the shops are very highly educated," Angervo explains. "We also have people called product specialists, who have been working for Alko for as much as 30 years, and within that time they have tasted every product that has ever been listed within themonopoly.

Their role is to reeducate their colleagues and pass the information forward. It’s the same in all the monopolies, the level of education is superior to any other major [retail] business." From another perspective, supermarket chains, although in favour of taking over distribution of wine and beer, are actually reluctant to distribute spirits for fear of being accused of spreading alcoholism.

Recently, one Alko outlet was ordered to close for two days after it was found that three bottles of spirits had been sold to a 16-year-old without checking her identity. There have been rumours of the monopolies’ collapse since the Baltic states joined the EU last year, so could the game finally be up? Of the three Scandinavian monopolies, Alko is certainly under the most pressure.

As soon as one of them topples the rest may fall. In these 21st century days of freedom of choice for all, monopolies are somewhat unpopular and there is a general consensus that they can’t go on forever.

However, the original philosophies of controlling excessive consumption while making a wide range of choice available to everyone at a fair and openly calculated price are commendable goals for any retail organisation.