This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Cool Bordeaux: terroirs come in from the cold

The 2022 vintage brought climate change into sharp focus for Bordeaux. Wendy Narby reports.

Spring frosts, a hot, dry summer, dangerously close forest fires and derogations to irrigate in a region dedicated to dry farming.

Appellations with cooler terroirs have traditionally struggled to get grapes to perfect ripeness year on year, are they now coming into their own as temperatures rise? Perhaps it’s time to reassess the less lauded Bordeaux appellations?

Cornelis van Leeuwen thinks so. He should know, he’s Bordeaux’s leading terroir researcher at the ISVV (Institut des Science de la Vigne et du Vin). He has an intimate knowledge of right bank terroir, having worked with Cheval Blanc, amongst others, and he recently turned his attention to the satellite appellations of Saint Emilion.

Satellites

To the north of Saint Emilion, the appellations of Saint-Georges Saint-Emilion, Montagne Saint-Emilion, Puisseguin Saint-Emilion and Lussac Saint-Emilion have long been in the shadow of their more famous neighbour. Although they carry Saint Emilion in their name, they don’t have the option of a Saint Emilion Grand Cru appellation and so cannot participate in the classification.

Given recent events, that’s perhaps not a bad thing. The origin of the name dates from the 12th century when Aquitaine was under the rule of King John ‘Lackland’. He decreed that only barrels that travelled less than a half day by cart to the port of Saint Emilion could carry the name Saint Emilion. Further away, they became satellites.

From Rustic to ripe

Although they have a lot in common with their more famous neighbour: similar terroir and Merlot dominated blends, they are often characterised as ‘rustic’, showing green tannins in challenging vintages. In the hot, dry 2022 vintage, when some Saint Emilion properties were given a derogation to irrigate, the satellites held up just fine, showing an elegant freshness in the primeur tastings.

Terroir

Maps of Saint Emilion and the satellites clearly show similar terroirs. Two types of limestone run along the right bank of the Dordogne, the harder ‘asteride’ limestone and softer Molasse du Fronsadais, mixed with deep layers of clay. Starting in the Cotes de Franc and Castillon they run across Saint Emilion and the Satellites, popping up in Fronsac on the other side of the L’Isle River and then again further north in the Cotes de Bourg and Cotes de Blaye.

These cool soils offer a thermal and hydric cushion, the bed rock water storage preserves fresh acidity and the deep clays give rich tannins. Unlike gravel and sandy soils they don’t radiate heat during the night.

Tellingly, in 2022 it was the gravelly ‘Pomerol corner’ of Saint Emilion that needed the derogation. This reserve of acidity is crucial for taste profile but also for vinification, protecting the juice particularly with less interventionist wine making.

How much cooler?

Van Leeuwen’s study showed the Saint-Emilion satellite appellations as generally cooler than the Saint-Emilion and Pomerol appellations. He used temperature sensors located in the vine canopy, inside the plots with highest temperatures recorded in the south-west of the appellations (Libourne) and the lowest in the north-east (Lussac commune).

Layer the temperature map on top of the soils maps and we see that, even with the similar soils, the temperature still remains cooler across the satellites.

Micro climates

The Right bank is higher and hillier than the Medoc, but we’re talking Bordeaux here, the highest point of 100m is in Puisseguin and around 80m in Lussac and Montagne. This elevation isn’t enough to really affect temperature but it does mean more exposure to cooling breezes, an air circulation that also helps with fungal diseases.

The countryside of the satellites is beautiful, with rolling hillsides eroded by streams and rivers, the plateaux of limestone covered with shallow to deep clay and silty-clay top soils. Sun exposure and elevations change across the satellites and within vineyards, offering a mosaic of terroirs that react differently to the climate. Those northern facing slopes that were once the worse plots are now becoming precious reserves of freshness. Properties tend to be larger than Saint Emilion and Pomerol, giving them the advantage of blending not only varieties but also these terroirs.

Not only ripeness

Vines take longer to establish themselves in these clay and limestone soils compared to gravel and sandy soils. Clay soils also have less nitrogen, giving less vigour. Once established, the deep roots have access to the hydric reserve in the subsoils. The cooler terroir also delays budding, flowering and ripening dates. Later budding gives some protection from spring frosts compared to warmer terroirs where earlier bud break makes vines susceptible to late spring frosts.

Traditionally these cooler conditions have favoured the aromatic expression of Merlot, that quickly suffers from an excess of heat and with a short picking window. Van Leeuwen’s study was not just a pat on the back and reassurance for the satellites. He worked closely with the Saint Elites, an association of eight family owned and run vineyards across the appellations.

Soil pits were studied on each estate and precise advice given property to property. For Brigitte Destouet-Bourlon of Château Guibeau, one of the instigators or the study, the results were the precise scientific confirmation of what they were already seeing the grapes coming in. This proof is a really useful tool to explain their specificity to clients and especially sommeliers who also find the subject fascinating.

As climate changes and temperatures rise, van Leeuwen recommended gradually increasing the proportion of Cabernet Franc and Malbec in the blends right across the appellations and vineyards. The Bordeaux blend continues to be useful tool in adapting to climate change.

More than terroir

By increasing the understanding of terroir, Kees was and is a pioneer of the move towards plot by plot precision viticulture and moving that into the cellar as plot by plot wine making. Wine quality is not uniquely dependent on terroir (topography, climatology, geology and soil) but knowing the terroir helps growers adapt viticulture.

Canopy management, planting density, agro-forestry, cover crops, leaf thinning are all tools useful in adapting to climate change. Two of the coolest, appellations, Lussac and Puisseguin have an obligation to be certified sustainable to qualify for the appellation (as does Saint Emilion).

In the cellar, stricter selection, whole bunch pressing, temperature control, use of terracotta all give more flexibility to wine making. You’ll spot experimental amphorae in a lot of cellars in Bordeaux, offering porosity without oak influence, adding freshness to the blend.

Oenologist Bruno Lacoste, works extensively across the right bank, Entre deux Mers (and further afield). He is also excited about the potential he sees for these cooler later ripening plots across Puisseguin Montagne, Lussac and Fronsac where limestone brings a touch of minerality to the fruit-forward and fresh wines.

Not only satellites

This awareness of the advantage of cooler soils is not limited to the satellites. At a recent tasting in Château Grand Corbin, classified growth of Saint Emilion, they enthusiastically shared their location the northern, traditionally cooler, part of the Saint Emilion appellation. Not something they would have boasted about in the past.

Fronsac

Traditionally known a cooler neighbour of Saint Emilion, Fronsac is also on the same bank of limestone, that carries its name and the harder asteride limestone at the ‘tertre’ and on the Saillans plateau. At the confluence of the l’Isle and Dordogne, rivers, proximity to the water offers some protection from spring and also cooling morning mists.

The deep clay here acts as a water reserve, controlling hydric stress on terroir known for slow maturing. In 2022, Sally Evans from George 7 was stunned to hear Saint Emilion were irrigating when leaves were still growing on her cooler soils.

Less celebrated

Following these pockets of limestone across Bordeaux identifies the less celebrated areas with potential to outperform their status and perceived image.

As well as Cotes de Blaye and Cotes de Bourg further north, Cadillac Côtes de Bordeaux on the right bank of the Garonne has some outstanding limestone cliffs. The North East of the Entre deux Mers has asteride limestone, as does the western edge of the Médoc.

It’s not only good for red wines, these terroirs are perfect for white. The limestone plateau in the south of Graves in Cérons and Barsac is the perfect example.

Cool running

As climate change, seems to be colliding with a global desire for fresher, fruitier and more precise wines, these cooler appellations could be the

answer. Here are some to try.

Satellites

Puisseguin Saint Emilion

Château Guibeau: An organic Merlot, Cabernet Franc blend from clay and limestone soils fermented and aged in large oak barrels to limit the oak impact.

Château Guibeau Pimienta: Following Van leeuwens advice they also make a 100% Malbec from similar limestone soils in neighbouring Castillon Côtes de Bordeaux. Accenting all fruit and freshness from young vines that see no oak.

Montagne Saint Emilion

Château Maison Blanche: Biodynamic blend of old vine Merlot and Cabernet Franc, grown on the cool clay limestone slopes on the edge of Saint Emilion.

Fronsac

Château George 7: 100% Merlot fermented in large oak barrels and stainless steel. Matured in traditional French oak barrels for 18 months. As well as the second wine, Le Prince, and a remarkable fresh Sauvignon Semillon blend, Bordeaux appellation of course but from the same fresh limestone soils.

Cotes de Cadillac

Château Biac: Situated high on the limestone hill overlooking the Garonne river this is a classic Bordeaux blend that illustrates a plot by plot approach. Merlot, and Cabernet Franc are grown on the clay and limestone with some Petit Verdot and Cabernet Sauvignon on plots of gravel and sand

The cooler corner of Saint Emilion

Corbin is the north-west corner of Saint Emilion between Montagne Saint Emilion and Pomerol, where the limestone slips away in favour of deep blue clay.

There are several properties that carry the name, two of my favourites are:

Château Grand Corbin: This Merlot Cabernet Franc blend has the power you would expect from a classified growth with a fresh elegance.

Château Grand Corbin Despagne: An organic Merlot, Cabernet Franc blend with a tiny touch of Cabernet-Sauvignon grown on blue clay soils with ‘crasse de fer’ iron influence similar to neighbouring Pomerol.

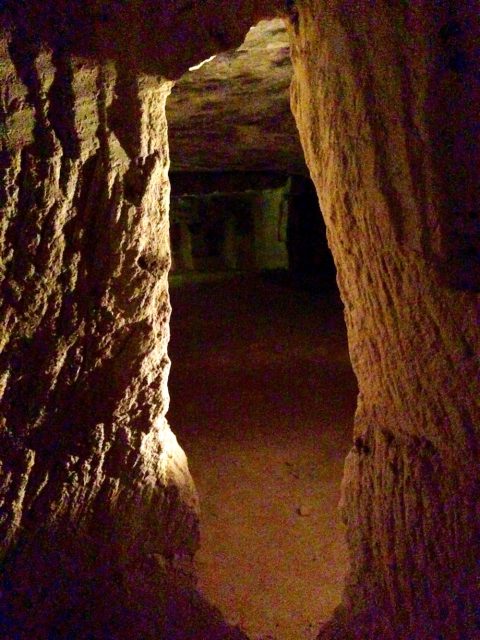

Entre deux Mers: The Quarry range from Chateau de Sours is made uniquely from plots on exposed limestone bedrock at the heart of the property. The red is a Merlot, Petit Verdot blend with a touch of Cabernet, also look for the Sauvignon Blanc dominated white and the Crémant Blanc de Noir with the underground cellars in the old quarry used for bottle ageing on the lees.

Listrac

Château Fourcas Hosten: Since an extensive soil study in 2010, Merlot vines have been planted on the clay limestone plots and gravel dedicated to Cabernet Sauvignon and Petit Verdot. They reintroduced an historic dry white planting on the clay plot near the chateau.