This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

VieVinum: 6 Austrian wine trends to watch out for

Louis Thomas heads to Vienna for VieVinum and looks into some of the key trends that could well decide the future direction of Austrian wine.

The immense imperial grandeur of the Hofburg, where VieVinum is held, is a reminder that Vienna was once the centre of a truly vast empire that stretched from Ukraine to Italy.

But while Austria honours its traditions and heritage, it certainly does not live in the past – Vienna today is the modern capital of a thriving Central European democracy.

In much the same way, Austria’s wine sector is far from stagnant. It is adapting while trying to preserve its identity, embracing new classification systems, grapes and styles.

It might be tempting to consider Austria as a ‘plucky underdog’ when compared to other wine growing powers like Italy and France – its almost 45,000 hectares under vine is less than half of the viticultural area of Bordeaux – but such a view is entirely patronising: Austria has millennia of grape growing history, and has been at the forefront of many a viticultural and oenological development.

Its wine scene is exciting, diverse, and ever-changing – simply put, producers from across the world would do well to learn from what is happening in Austria.

Single life

The biggest development in Austrian wine, arguably this century, was last year’s approval of a new vineyard classification system.

In his Austrian Wine Update presentation, Chris Yorke, the CEO of the Austrian Wine Marketing Board, joked that “we love a good regulation in Austria”.

2023 saw Thermenregion become a DAC, or ‘Districtus Austriae Controllatus’, an addition which completes the regional structuring.

“We have spent the last 20 years on a really important journey, defining our DACs and the typicity of each region, he said. “This forms the basis of our next 20 years…now we have the ability to classify those single vineyards, as long as they fit into the DAC system.”

Under the new system, individual vineyard sites can be classified as Erste Lage (effectively Premier Cru) or Grosse Lage (Grand Cru).

Yorke shared that he expects the first classifications to go through next year, and in order to achieve these, producers’ vineyards must meet certain criteria.

“You have to show the historical significance of the vineyard, the homogeneity of the soil, and the international and national ratings of the soil,” Yorke continued. “Austria is the first wine country in the world to do this nationally.”

“We often compare ourselves to France, but if you compare this to Burgundy or Alsace, it’s very different.”

But not everyone is happy. Discussions with producers showed how divisive the issue is, with some suggesting that it is too much to soon, discriminated against newer producers (especially in Burgenland), and confused things – on the other hand, there were plenty who were highly enthusiastic about the new classification system, seeing it as a positive step towards Austria selling its premium wines based on the quality of their diverse terroirs.

Yorke compared the sometimes heated discussions to a game of tennis: “We have a very noisy consensus-building process in Austria.”

That noise does not show any signs of dying away just yet.

Vienna Calling

When one thinks of wine regions, images of rolling hills in remote reaches spring to mind, and Austria certainly has these in buckets, but its capital is also a wine growing region in its own right.

Indeed, there are 582 hectares within Vienna’s city limits that are under vine, with the Wiener Gemischter Satz (or Viennese field blend) achieving DAC status in 2013.

2023 was, according t0 figures from the city, the second best year on record for the number of visitors coming, with 17,261,000 overnight stays, a 31% increase on 2022’s level, and only 2% short of 2019’s pre-pandemic peak. Of course, these visitors come to see the grand architecture, the opera, and to queue for an hour outside Café Central for a slice of sachertorte – but perhaps they should be going for a winery tour and tasting as well.

Though perhaps not the romantic idyll many people have when planning a vineyard visit, Vienna has a number of assets when it comes to wine tourism – mainly in terms of ease of access.

Georg Grohs, head of sales for Wieninger and Hajszan Neumann, estimated that from central Vienna, it was possible to get to the wineries in “longer than 40 minutes” using the city’s trams and metro.

When they arrive, for €28 they can go on a tour, and, Grohs noted, this offering is attracting an international audience – the day before we speak, a group of Czech tourists had visited, and many come even further, with travellers from North America and Asia often including a visit as part of their trip itinerary.

“I think it’s the only city in the world with this many wineries in it,” he remarked.

Wieninger and Hajszan Neumann are far from the only ones – Cobenzl, which is owned by the city of Vienna itself, makes a point of offering its tours and tastings in English to cater to overseas visitors, though it should be noted that the biggest foreign contingent visiting the city, according to the data, comes from Germany, where the language barrier is less of an issue.

Given that it seems liquid limits on flights may soon be a thing of the past (though UK airports have delayed their adoption of it), this could present a huge opportunity for visitors to the city to buy wines at Viennese cellar doors and transport them in their hand luggage – the Wieninger labels, which depict the city, could certainly make the bottles good souvenirs too.

The Other Veltliner

Grüner Veltliner is, by quite some distance, Austria’s most-planted grape variety, making up almost a third (32.4%) of total plantings – but there is a variety that shares its surname, though comparatively little genetically, that might just have a small, but promising commercial future of its own.

Roter Veltliner, which stands out for its pink, Pinot Grigio-esque skin (hence the name, with ‘roter’ meaning ‘redder’), likely originated in Valtellina, Lombardy, but today its heartland is across the Alps in Wagram, to the north-east of Vienna.

The grape has not always enjoyed a glowing reputation, as world-renowned sommelier Pascaline Lepeltier explained when telling the story of when she was asked some years ago to taste a wine from Andorfer Martin & Anna: “I thought Roter Veltliner was a boring, fat grape at the time.”

But Lepeltier described the experience of tasting the wine (Terrassen 1979), positively, “as a slap in my face, it was so far from my image of Roter Veltiner” – she attributed the quality of this particular wine to the age of its vines, the altitude at which they were planted (317-323 m.a.s.l.), and the biodynamic viticulture.

Indeed, describing the varietal characteristics of Roter Veltliner is something of a challenge, as Lepeltier alluded to: “It is able to transcend varietal characteristics and express its site.”

Given the push for single vineyard classification, a grape variety that mirrors terroir like Roter Veltliner could be poised for big things, though it only has 0.4% share (just shy of 200ha) of all vine plantings in Austria at present.

“There is no bad grape per se,” Lepeltier argued, “it depends on where you are and what you want to make.”

Roter Veltliner is certainly a grape that can be made into an awful lot, as the growers of Wagram have demonstrated.

The reddish skin can lead to a luridly orange wine, such as Familie Bauer’s Urig, the 2021 vintage of which macerated for almost a year, and Leth straddles both ends of the spectrum, creating a traditional method sekt and a sweet beerenauslese from the grape – Roter Veltliner can create a wine for every occasion, and consumer demographic.

However, it has an unfortunate quality that is preventing it from being more widely-cultivated: it is very prone to disease.

Judith Mehofer revealed that family-run producer Weingut Mehofer has been organic for more than 30 years, but shared that Roter Veltliner does make life difficult in the vineyard when manmade sprays aren’t permitted: “It has tight bunches, so there’s a risk of fungal disease.”

To combat this, the bunches of Roter Veltliner are thinned by around 50% in late June/early July to give the berries greater ventilation, reducing the humidity, and therefore the risk of rot taking hold.

“We also select the vines that perform well,” she shared.

Given that around 22% of Austria’s producers practice organic/biodynamic viticulture, going for a variety that requires such drastic management might not seem to be the optimum move, but its aforementioned ability to show its place of origin could certainly make it an attractive proposition for growers outside of Wagram, Kamptal and Kremstal keen to create premium, terroir-driven wines. As a taste of the 2008 Schuster Valvinea Roter Veltliner proved, it can make wines that wear their age exceptionally well too.

PIWI Playhouse

There is of course a category of grapes that is immune to Roter Veltliner’s fungal frustrations – PIWI, a much-needed abbreviation of the German ‘Pilzwiderstandsfähige Reben’.

A small number of these fungal-resistant grapes are permitted for the production of Austrian Qualitätswein, including the white Blütenmuskateller and Souvignier Gris, and the red Ráthay. Others, such as Cabernet Blanc and Regent, can be used in wines without a designated geographical origin.

PIWIs are still yet to win over some in the wine world who suggest that the desirable quality is not there, but the overall direction of travel is one of acceptance.

“Hybrids have existed forever, we are hybrids – it seems like a dirty word today,” remarked Lepeltier. “They can express terroir – they just need to be given time…It’s about a holistic point of view.”

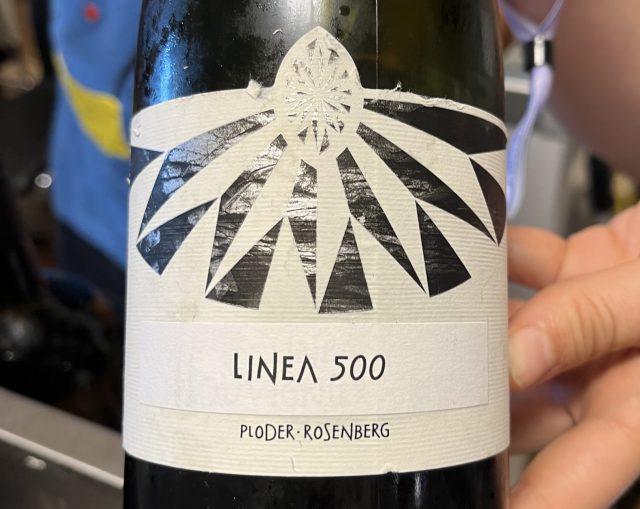

Among the Austrians to embrace this perspective is Weingut Ploder-Rosenberg, a biodynamic and organic-certified producer that is gaining a reputation for its Souvignier Gris, such as in its single varietal Linea 500.

“We started to plant them in 2004 because we are located in Steiermark and we get a lot of rain – our goal was to work with nature, not against it,” commented Selina Weratschnig.

“For us, PIWIs are not a trend,” she argued. “If you’re a farmer, you have to look at your soil, your climate, and then pick a plant that fits it.”

“Each year, a lot of our organic and biodynamic colleagues lose a lot of berries to fungus. With PIWIs, it’s not about having a bigger harvest, but a more stable, consistent one each vintage to supply the market with.”

Weratschnig even suggested that PIWIs are saving the lives of viticulturists on Steiermark’s precariously steep slopes, as they require less attention than other grapes, reducing the time growers have to spend in their vineyards, and therefore the risk of “falling out of their tractor and dying.”

As for Weratschnig’s response to the PIWI naysayers? “At the end, it’s just wine, made out of grapes.”

“I don’t like to say ‘it’s good for a PIWI wine’, it has to be good as a wine – if it’s also made from a PIWI grape, awesome,” she concluded.

Light Blue

Blaufränkisch, the name meaning ‘Blue Frankish’, is Austria’s second-most widely-planted red grape, after its offspring Zweigelt, with 5.8% of the country’s vineyard area devoted to it. Its dark, tannin-rich skins result in inky wines to match, and it

But Austria, like the rest of the wine world, is moving away from the heavy, aggressive wines Blaufränkisch can produce (some of which have the quality of chewing on a rubber tire within whiffing distance of a jam factory) in favour of lightness and freshness.

The variety, also known as Lemberger in Germany and Kékfrankos in Hungary, certainly has its acolytes, including Raimonds Tomsons, the 2023 winner of the ASI (Association de la Sommellerie Internationale) Best Sommelier of the World competition.

“I believe that Blaufränkisch is, along with classics like Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir and Syrah, one of the greatest red varieties in the world,” he suggested.

Presenting Dorli Muhr’s 2019 Blaufränkisch Ried Obere Spitzer from Carnuntum DAC, Tomsons said that it “reflects the global trend of less extraction, less new oak, more finesse”, leading to a “very elegant, very fresh” wine.

Muhr herself apparently compared her 13% ABV Blaufränkisch Ried Obere Spitzer to a ballerina: “Very strong, very balanced, very muscular, and no fat.”

Tomsons, noting the audience’s enthusiasm for the wine, did point out that the single hectare plot of Blaufränkisch yielded only 800 bottles, making for a “commercially ridiculous” product.

Blaufränkisch is also a useful blending component alongside the likes of Merlot, Syrah and Zweigelt – lending black fruit, herbaceous aromas.

Of course, climate change is making life harder for producers across the world, and the Austrians aren’t immune, with some producers even leaving their regional classifications in protest over inaction regarding the environment.

Fortunately, Austrian growers have a grape up their sleeves in the form of Blaufränkisch.

“It’s quite drought resistant,” said Tomsons, “so it has very good potential in a changing climate.”

When it does become too hot for some grapes, such as Merlot, it seems that more and more winemakers will turn to Blaufränkisch – though they will have to handle it with care in the cellar if they are to create something ‘elegant’ that appeals to modern critics.

Rising from the ashes

The issue of what volcanic soils actually do to a wine is a complex one – at various points I’ve had people in the trade refer to the liquid in the glass having an ‘energy’ to it, the sort of descriptor that raises more questions than it owners.

As the name implies, Vulkanland Steiermark DAC, the eastern portion of Styria, is not shy on trading on its geology, with the (fortunately) extinct volcanoes credited with giving the wide range of grapes grown their unique qualities.

Klaus Fischer of Fischer Weine credited volcanic soil with giving his Morillon (the local name for Chardonnay) “more spiciness and a little bit of smokiness.”

“It makes the wines powerful, mineral-ic,” said Weingut Frühwirth’s Fritz Frühwirth, particularly of his Gelber Träminer from the area of Klöch.

Georg Winkler-Hermaden of Weingut Winkler-Hermaden said that the soil helps to bolster the structure, giving his single vineyard Sauvignon Blancs “20 years” of ageing potential.

However, Vulkanland Steiermark DAC’s soils are not as clear cut as the branding suggests. In truth, the region has a huge mixture – sand, clay, loam (red and brown), gneiss, slate, gravel, with both calcareous and non-calcareous sub-strata – and don’t forget the influence of the warm, dry Pannonian climate either. Simply put: don’t be disappointed if you buy a wine from the region and have to search hard for its volcanic ‘quality’.

This is by no means a mark against the region – in fact, once you get past the notion of ‘volcanic wines’, you can open yourself up to some truly remarkable creations.

For Tomsons, Vulkanland Steiermark DAC is capable of giving even the Burgundians a run for their money.

Presenting Pfeifer’s 2020 Chardonnay Ried Schemming, Tomsons said: “I chose this wine as it is a kind reminder that, as Burgundy has become so expensive, this is a great alternative.”

Just 1,500 bottles were made – Pfeifer sells its 2021 vintage of the wine online for €31.20.

“This is made in a very Burgundian style – whole bunch press with a bit of skin contact and aged in French oak…It really displays a wonderful texture – ‘21 is one of the finest recent vintages, full of tension and freshness,” he said. “It’s a kind reminder that there are really great Chardonnays outside of Burgundy, California and Australia.”

The quality and the diversity of the wines of Vulkanland Steiermark DAC do show that while soil plays a role, clever winemaking is still the key.

Producers, though perhaps not the regional body, are cautious of relying too heavily on the volcanic angle in their marketing.

“For us it’s good that volcanic wines are becoming a trend – for 20 years no one cared that we were a volcanic region,” remarked Fischer. “But every 10 years there has to be a new trend, so maybe they’ll be speaking about schist next!”

Final thought – the problem with pursuing pigs

As Fischer pointed out, trends, by their very nature, don’t last.

Ingrid Groiss, of the eponymous wine estate in Lower Austria’s Weinviertel, cited the example of how in the 90s, when Parker was at his apex, every producer wanted to make big, bold, oak-heavy wines – “now the focus is on elegance and terroir”.

“Trends are coming and going, they’re always changing,” she argued. “If you’re a winemaker who just focuses on trends, then you are always behind the trend – you will always lose if you just watch trends. It’s more important to focus on your grapes, on your region, on your wines – this is a much better approach in the long term.”

To summarise this sentiment, Groiss used a quintessentially Austrian expression to describe those who follow fads:

“Jeden tag eine neue sau durch das dorf jagen.”

“Chasing a new sow through the village every day.”

Austrian wine is undeniably at a very exciting point – but only time will show which developments will stay the course, and which will be just another new pig.