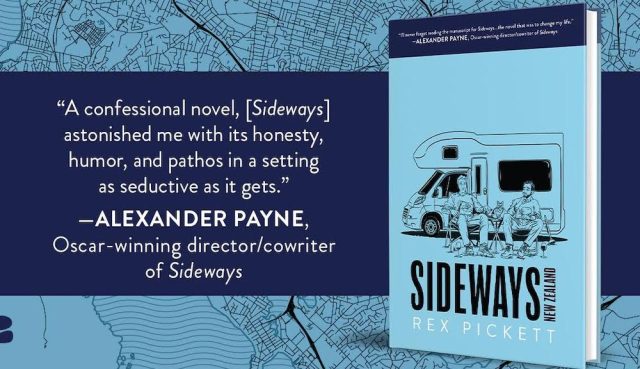

Rex Pickett: ‘wine isn’t a democracy’

The legendary writer of Sideways talks to the drinks business about his latest book, his views on Chilean and New Zealand wine and, of course, Pinot Noir and Merlot.

There is a well-known shorthand in the wine world for the recent growth of Pinot Noir and the decline of Merlot: the Sideways effect. In the years before social media and the age of the ‘influencer’, Rex Pickett’s novel and the subsequent film directed by Alexander Payne had a phenomenal impact.

Now after two decades, Pickett is returning to the source. In an exclusive interview, Pickett tells db that his latest book, Sideways: 20, which he is currently writing, will see his popular character and alter-ego from the novel and film, Miles Raymond, return to Napa. In doing so, he will revisit the places that were the wellspring of his journey as a writer and wine lover.

Pickett’s story is perhaps typical of many Californian would-be writers and those hawking screenplays. He had years of struggle, which were followed by literary acceptance, then a Hollywood director optioning his work, and suddenly becoming famous and at the centre of an Oscar-winning film. Although, the journey was far from a straightforward rise, and it should be noted that when Payne took on the novel to be developed into a screenplay, it was still unpublished – itself a fascinating story that Pickett has previously expanded upon.

Indeed, Pickett’s narrative begins, as he tells us, rather wonderfully and like the start of the hero’s journey in a screenplay: as an unpublished writer at a California wine tasting. He says he “owes everything he knowns about wine” to a shop in Santa Monica called Epicurus, and the merchant Julian Davies, especially the “infamous Saturday tastings where I learned about various wine styles”. It is a rather delightful example of the power of wine education, and how a deep passion for a subject can be formed through such events. It’s hard to image Sideways not existing and Pickett’s passion for wine being stillborn, but perhaps that could have happened if he hadn’t gone to Davies’ tastings.

The impact of the film

Then, down and out in California, loving wine, he wrote the book that would change his life.

Much of Sideway‘s wine industry reputation lies in two short sections of the Oscar-winning film, although the whole film and book does centre mainly on the wine world. One section is only seconds long, and the other is a couple of minutes. The first segment sees the main character Miles Raymond (played by Paul Giamatti) — as noted, Pickett’s “alter-ego” — pulled outside of a restaurant by his friend, Jack (played by Thomas Haden Church) when they have gone to dinner with two women. At this moment, Miles delivers a stinging putdown on drinking Merlot.

Pickett’s infamous Merlot line wasn’t included in his novel, but was found in one of the previous drafts. Director Alexander Payne discovered the line in the archive of material —he received all of Pickett’s Sideways-associated writings, including previous drafts and notes, when he had optioned the work — and decided to add it into the final screenplay.

Such was the impact of this brief moment in the film that Merlot sales in the western United States dropped 2%. In fact, the idea of the ‘Sideways effect’ on the variety’s global sales continues to be felt even to this day, according to some reports.

Admitting he’s had to answer the question about the Merlot line “many, many times”, Pickett says “there’s a lot of different answers to it”. The reason this harsh moment of dialogue, and not the many other poetic moments in the film, has survived over the years, is the sheer power that the actor Paul Giamatti delivers his view on the grape variety.

“The Merlot line hits because it is said with such venom and invective,” he says.

But Pickett reveals it is more complicated than at first glance. He continues: “Let me give you a different take. If you really watch that scene, you can see what’s really happening; Jack is trying to coach Miles on this evening going well, so he can cheat on his fiancee. For Miles, throughout the novel and film, this isn’t his main priority.

“His main priority is to get his novel published, because he feels like such a loser. He is reproachful of Jack, and Jack cheating on his fiancee. He’s a moralist. And so Jack is trying to coach him on it, and Miles has been wine tasting all day.”

“Jack just assumes that he thinks Merlot is tantamount to wine philistinism, which is what it was when I was going to these wine tastings in the 90s, and what opens the novel in Sideways: the Wine Cave. But that’s not in the movie.”

Plonk

Pickett adds he’s glad when people approach him and aware that Payne added the infamous line, as it means “they actually read the book”.

He continues: “So it’s a combination of Merlot becoming synonymous with cheap red wine, plonk, and synonymous with wine philistinism, at least in the group I was in.”

This view of Merlot came from living in Santa Monica and mixing with wealthy people who had a strong view on grape varieties.

“It was an interesting mix,” Pickett says, “and I got to see the classism and the elitism and the snobbism of the wine world. All of which I deplore.”

He sighs, and continues, “I just fucking deplore it. And so Merlot kind of got in the way.

But back to the Merlot scene, Pickett continues: “Miles is basically just saying to Jack, I’m going to be a wildcard tonight. So when Jack is coaching him on that, his frustration isn’t with Merlot, his frustration is with Jack, he does not want to be at this dinner.”

So there you have it: Miles doesn’t (really) have a problem with Merlot. He has a problem with his friend.

Varieties

Pickett is refreshing on his views on other varieties, and doesn’t hold back on his views of other grapes. Perhaps this isn’t surprising though, considering he penned the infamous Merlot line.

“I’m not sitting there trying to diss on one grape,” he says, laughing, and then adding, “because, you know, there’s other grapes too I could mention. For instance, I spent six months in Chianti, and I had trouble finding a Sangiovese that I like, to be quite frank with you. But that’s a different story, and a different country.”

Pickett is also rueful on the impact of the Sideways effect, and how it has shifted the wine world.

He says: “The people who have suffered are those who make wines needing 10-15% Merlot to blend, to soften those harsh tannins of the Cabernet, and there isn’t enough Merlot out there for them. And so they’ve been going more 100% Cabernet.”

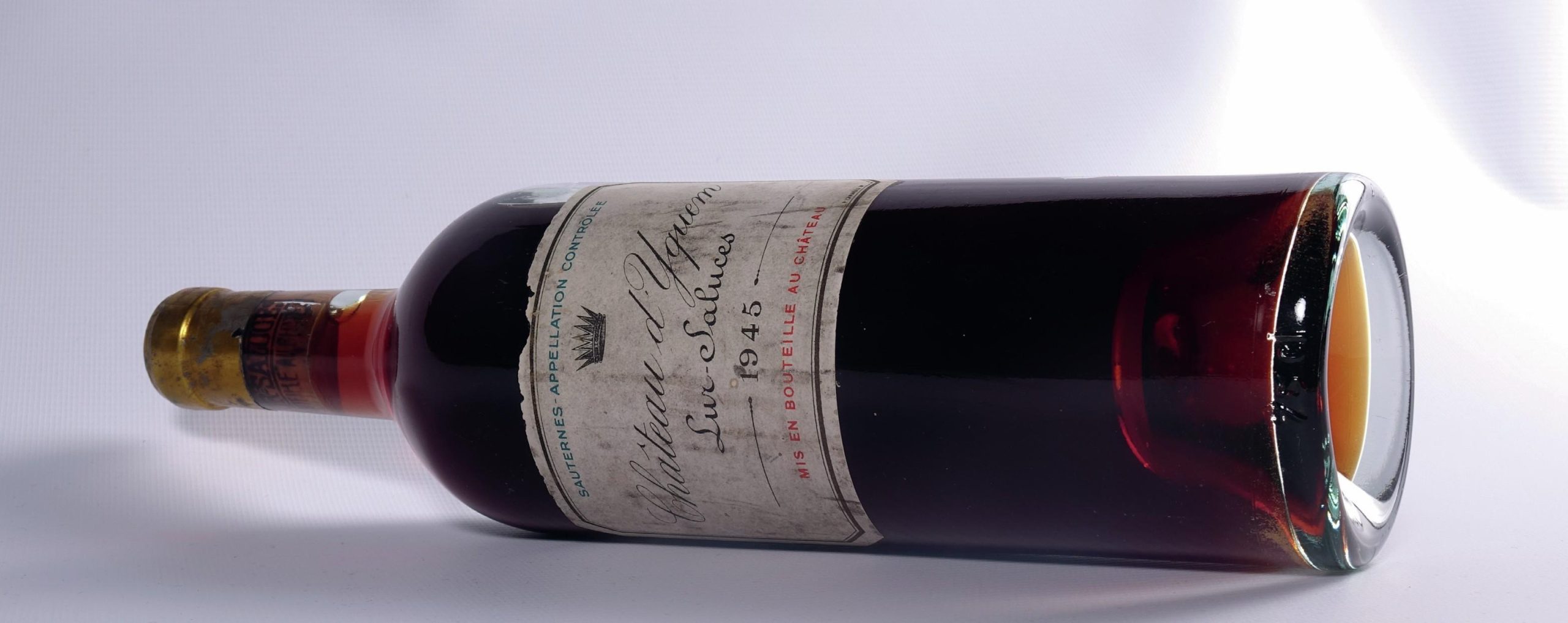

This might be Pickett making a thinly veiled reference to the other Merlot in the film —Miles’ bottle of 1961 Château Cheval Blanc, itself a blend of Merlot and Cabernet Franc, and which he opens and sips with a burger in a fast food restaurant in a concluding scene

Interestingly, Chardonnay also gets a mild attack in the film, with Miles saying it is too oaky and buttery. But this didn’t impact sales, or certainly didn’t get the publicity associated with the Merlot line. As Pickett elaborates, it is delivered during a reprieve in the film, where tension is much lower and the scene, “just fades out”.

Indeed, when quizzing other wine lovers on this moment in the film, very few remember that Chardonnay actually got a more eloquent and considered putdown than Merlot by Miles. It’s always interesting to see how, even before our modern culture of social media and memes, one moment can be remembered above all others.

Pinot Noir

The counterpoint to Merlot is the other critical player in the so-called Sideways effect: Pinot Noir.

In a scene, which may be the greatest ever wine-based dialogue put to celluloid, Miles and his romantic interest Maya (an astonishing performance from Virginia Madsen, who was nominated for an Oscar) discuss Pinot and wine in general.

As Pickett states, the scene “speaks for itself”, and perhaps it is best to simply watch it below and understand the power that it portrays. Viewing it now, it is unsurprising that the film went on to win an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

According to wine industry analyst Gabriel Froymovich, Pinot Noir production in California has increased roughly 170% since Sideways was released. If Merlot was negatively impacted by the film, that poetic description of Pinot by Miles led to an explosion in the variety.

But despite this broad success, there does appear to be a new issue: why, in spite of all this poetry and talk of well-crafted wines and artisanal production, are young people not taking to the grape? Last year, Silicon Valley Bank reported 58% of consumers over the age of 65 favour wine over other alcoholic beverages, but for millennials and Generation Z it was barely a quarter.

According to Pickett, and sounding wonderfully like Miles, the problem is the consumer’s attitude towards wine, and ultimately what drinkers consider as important.

He continues: “The real problem is is the beauty and the poetry of wine. Once you start to make wine that you’ve taken vintage out, and once you take vintage out, I think you’ve lost the poetry of wine.”

Quality

Is this why young people are drinking less wine then? Pickett thinks winemakers need to talk up wine’s vintage and outright quality over other drinks, and be honest about its place in the hierarchy of consumer purchasing.

He says: “You’re not getting a very high quality drink at a lower price point. When we’re talking about vintage, and the incredible production and artistry that goes into wine, then that is why people fall in love with it.”

“But this isn’t really happening.”

Pickett explains how when he gained knowledge about barrels it was an instructive lesson. He says: “I did a piece about a year ago on barrels, they had me hosting. I discovered that only 4% of wines even see wood. So we’re talking about really commercial, industrialised wine most of the time.

“I hate to say it, because I’m not a rich person, either, but because I’m in around the wine business, I get to partake. People send me wine. And I don’t think Pinot even begins until US$30. Underneath that, I’ve had some US$25 and US$20 Pinots which were nice, but it doesn’t start to really express the grape.”

“It doesn’t start to really showcase all its wonders and its potential until people can do things like have barrels, basket presses and gravity flow.”

As an example of this point on price, Pickett outlines his favourite wine right now, Ancien wine from Sonoma.

He continues: “It’s just one of my favourites and I just blogged about the owner, Ken Bernard, and he’s just doing everything right. But he is not doing it for the money. He’s obviously doing it for the love of it. I’m sure he wants to make money, of course. But his wines, they cost US$50-70 a bottle. And to tell you the truth, they’re worth over US$100 a bottle, but he can’t get that.”

Pickett pauses, and concludes: “Ultimately it is what you value in life. I see people who put gas in their truck that gets eight miles to the gallon. That’s their priority. But my priority is drinking wine. Once you reach a certain point with wine, it’s kind of hard to go back to a US$15 or US$20 bottle of Pinot.”

Literature

Although it may be considered elitist to talk up the ‘art’ of wine in relation to its value, Pickett believes producers should lean-in to the value of their product, in the same way other luxury and technological goods manufacturers do.

“I guess it’s sort of like literature or film,” he continues, “Once you develop an aesthetic sensibility, it’s hard to read page-turning kind of stuff. You’ve developed a sensibility.

“And that’s one thing that drew me to wine because it does have its similarity to literature and film. It’s hard to kind of go back to a less expensive wine that’s gonna draw on a younger audience.

Partner Content

But Pickett admits this is a challenge, and consumers have to come face to face with the complexities of the wine world and its costings.

He continues: “I think what’s going to draw them in is when they really taste some of the best of the best. But none, including me, are going to get to taste Burgundies for instance.”

“You developed that palette, you have to be able to taste those wines. And I know I wrote about them in Sideways, but I didn’t drink them. I’ve been fortunate to know some people up here who have who have access to those wines, and they invite me to things and I’m drinking these ethereal, incredible wines, but I know they’re US$200-500 a bottle.”

“I can’t afford that, you know. Unlike for instance, literature or film, and not to digress…but wine is not a democracy.”

“No matter who you are, you can read War and Peace. You can see Lawrence of Arabia or great cinema. But you can’t all drink a DRC.”

He pauses, considering his answer: “So I’m not quite sure what the answer is, because I think if they start to cut corners and use wine, and I meet a lot of winemakers and to make wine really good, that really expresses that grape and that terroir…it costs money.”

The other Sideways

Pickett may still be regularly answering questions about the original Sideways book and film, but he hasn’t been standing still for the past 20 years.

He has created a body of work about his alter-ego Miles, travelling across the world on various adventures to other wine regions, including Oregon, Chile and New Zealand, before his latest novel brings him back to California.

Pickett explains how his second book is being reissued as Sideways: Oregon, through his new publisher Blackstone. All of the Sideways novels are being presented in beautiful hardback novels now, which is the first time the original novel has been in such a format.

“This year is the 20 year anniversary of the film Sideways in October, so I decided I would do all my books. I’m so happy Sideways: Oregon is being reissued, because a lot of people think it’s one of the best of the four novels. It’s a very poignant story,” he explains.

Sideways: Oregon

He tells how readers often see the texts as “road movies” or “road novels”. What is very clear is that Pickett really does sees Miles Raymond as a variation on himself, and he visits the locations ahead of writing the texts, and gets into the culture and understanding of the region’s producers to “find the story”.

Speaking about Oregon, he says: “It’s about a 4000 mile road trip. Sideways is not technically a road move, but is actually what I call a ‘sojourn movie’, because they go to one place and they park their ass.”

So, the novels are based on lived experience, with Pickett visiting vineyards and producers himself. Through placing wine at the centre of the text, Pickett draws a clear parallel between the art of wine and the experience of living.

Sideways: Chile

On Sideways: Chile, Pickett took a slightly different approach, visiting as a guest of organisations Wines of Chile and Pro Chile, who offered him the concept of “why don’t you bring Miles and Jack down here?”

He said although he understands the groups wanted a creative work, which would “reap the benefits of the Santa Ynez Valley”, but he was also “trying to find a story”, and had to “find the characters”.

Pickett explained that he “did the tour” but that it “wasn’t really doing it for me”, and, just like Miles, he had to “discover and break through on my own.” In his search for his own take on the Chilean wine scene, Pickett went to its independent wine producers movement called MOVI, especially Derek Mossman’s Garage Wine Co.

He continues: “I broke away a little bit in Chile and started to discover MOVI, which is movement of independent vintners.

“I met Derek Mossman and some others, who helped me a great deal. I got to meet these real off-the-grid winemakers. I’m always interested in the small ones, the producers who are doing it for the love of wine. And they’re not really doing it for the money.”

Through this experience he was able to also discover some other winemakers, including one that he was particularly passionate about.

“I was able to discover Viña Casa Marin’s winery,” he continues. “It is just an incredible wine story. There’s a woman winemaker there, María Luz Marin, and she’s just making wines in the Casablanca Valley that were to die for.”

“But I found you know, as you get down south of Santiago, and people talk about Maipo Valley, it is very touristy.”

As well for Pinots, he was fond of Casa Marin in San Antonio, Garces Silva’s Amayna in Leyda, and Casas del Bosque in Casablanca, he said.

“And they’re doing stuff with certain indigenous grapes”, he explained, “And that’s what interests me, it is the discovery of the small people who are often off the edge off the grid.”

He paused, and added: “I’m not interested in the big ones, and the big ones know I love that and respect it.”

This is a core concern of Pickett, as we can see. For him wine isn’t simply a manufacturing process of a mass-produced beverage. It is much, much more than that. And it isn’t always the small producers who are doing the exciting things.

He said: “I understand 50% of wine is big wine. But money is not always a bad thing. Money allows (producers) to do experimental projects and try other things.

“Some of the small winemakers don’t have the money to experiment with biodynamic or basket presses and other other things that might be cutting edge.”

Sideways: New Zealand

So what was the kernel of his other work Sideways: New Zealand? As with Pickett’s creative process, the book was never going to be a straightforward progression for Miles and Jack.

He continues: “There was less pressure on New Zealand. Actually less pressure because they the funding was was different down there.

“They really mostly helped me with infrastructure as opposed to Chile. In New Zealand it wasn’t a contractual thing, it was more like, you’re going to help me find these places, so I quickly discovered Central Otago on the south of the South Island.”

He smiles as he gets onto discussing his favourite variety: “Yeah, it was 80% Pinot Noir grown in these soils, that have 3% organic matter and schist soils that are very, very hard scrabble. You barely even grow weeds in them. So that interests me, wine at the edge of the world.

“But then there’s the story. I’ve come up with a story what’s Miles doing there? It’s 10 years later, and so I started to think, maybe he’s kind of left the known world.

“And he’s, as I have, been living a peripatetic life. It’s not all autobiography, obviously there’s fiction in there, but I put a lot of myself into the work, and I think it’s what lends it verisimilitude.”

“He’s written a book, he’s gonna go on a book tour, and he’s found a publisher. But the publisher kind of does a bait and switch on him. Instead of it being a real proper book tour. It’s put them in a camper van with Jack. And that’s what I did: a camper van and book clubs.

“It was quite an experience. New Zealand is the book that New Zealand gave me.”

The commercial side

Coming back to talk about the wines in New Zealand, Pickett comments on its most famous export.

“New Zealand has its commercial side, 67% of the production there is Sauvingon Blanc,” he continues, “a huge percentage goes straight into Kim Crawford and Villa Maria. They make recipe wines, they sell a million cases just in the US alone. They make wines in a facility. They make wines for the Asian market, they make wines for the UK market that are different, with different levels of sweetness and acidity.”

He pauses, “I have a lot of problems with that. It’s not what it’s really not what wine is about for me.”

“It probably was all made possible because of Cloudy Bay back in the ’90s, which just got this incredible press. And they made this certain kind of flavour, I don’t know, but I guess people call it ‘grassy green’. It is a kind of a lemony-limy Sauvignon Blanc, and and they just commoditised it, let’s be honest.”

But Pickett explains that he did meet many small winemakers on his trip.

He continues: “I met this guy Mike Eaton of Eaton Wines, who took meet to a collective, and it was all young winemakers. Some of them just had one barrel of Sauvignon Semillion, and they were experimenting with doing different things.”

Another winery that Pickett admired was Pegasus Bay, which was a “little bit bigger” — “they are doing some really interesting things”, he said.

The return home

Returning back to Sideways: 20, Pickett highlights the similarities between New Zealand and California. “It’s the same in Napa, Sonoma,” he says, “there’s big wineries up here. And they’re making it on their names. They’re making it on their reputations.

“But they are also making, to some extent, recipe wines. They’ll go into the facility and use additives, they’ll use centrifuges and this is well known in the business.

“And there’s some people like Ken Bernard, Julien Fayard and some other small winemakers up there. And in Anderson Valley, of course. They are all still trying to be purists.

He concludes: “And those are the people I gravitate to.”

You can purchase Rex Pickett’s series of Sideways novels from his website here.

Related news

Fells becomes exclusive UK distributor of Clarendelle

Fine wine defies downturn as US$250-plus bottles keep selling