This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Why Biondi-Santi’s evolution begins in the vineyard

During a visit to London earlier this week, Biondi-Santi CEO Giampiero Bertolini shared how the famed Brunello di Montalcino producer has adapted to survive and thrive.

Biondi-Santi is widely credited as the “founder” of Brunello di Montalcino, the famed wines made from Sangiovese grown in the area of the town of Montalcino in southern Tuscany.

Bertolini began by giving a brief lesson on the company’s history, noting how Clemente Santi began trying to create age-worthy, single varietal wines in the mid-19th century.

His grandson, Ferruccio Biondi-Santi, would continue this work, as Bertolini explained: “His wines had a high reputation, because he was packaging Sangiovese in a Bordelaise bottle, not a fiasco, as was traditional in Tuscany.”

In 1888, the first bottle to carry the name ‘Brunello di Montalcino Biondi-Santi Tenuta Greppo’ was unveiled.

“I like to remember two other members of the family too,” Bertolini explained. “Tancredi, Feruccio’s son, who was an incredible winemaker and consultant to estates across Italy. He became famous because in 1967 he drew up the specifications for Brunello di Montalcino when the DOC was created. That was a recognition of the family’s ability to produce high quality wine in a very specific way.”

“Tancredi also protected all of our riservas during the Second World War when the Germans invaded by walling them up in the cellar. Today we still have all the riservas since 1888 thanks to Tancredi.”

The other family member Bertolini singled out was Franco, Tancredi’s son: “Franco was a great man, a real technician – he was more austere than his father. During the 1970s, he introduced clonal selection, and would identify one specific clone from the estate, BBS11 [Brunello Biondi Santi 11]. Today we are still using this clone – it makes up about 60% of the vineyards.”

Franco’s son Jacopo, would sell Biondi-Santi to Christofer Descours, who runs EPI Group which also owns (among others) Charles Heidsieck Champagne, Piper-Heidsieck Champagne, Rare Champagne and has a minority stake in Biondi-Santi’s importer Liberty Wines, in late 2016.

While no members of the Biondi-Santi family are currently involved with the winery, Bertolini, who worked at Tuscan wine giant Frescobaldi until 2018, suggested that “the DNA” was still very much in how it operates, as many of the technicians in the vineyards and winery working there today were present before the sale.

Bertolini expressed his belief that since Biondi-Santi changed owners, the focus has shifted to “preparing for the future”.

As Bertolini revealed, those preparations have been primarily in the vineyard.

Understanding the soils across the 33 hectares of the estate’s vineyards has been key. In 2019, Chilean terroir aficionado Pedro Parra paid a visit to Biondi-Santi. Parra was eager to get beneath the surface, quite literally, and discover what sets one of Italy’s most revered producers apart: “He dug 33 big pits, and discovered a huge heterogeneity in the soils.”

These soil types ranged from marly schists in the eastern I Pieri vineyard to those with more clay content in the lower-lying northern site of Pievecchia.

“After that study, we have isolated 12 different parcels,” Bertolini explained. “The purpose is to really improve the quality by having more ingredients for the blending of Sangiovese.”

Soil parcellation isn’t the only variable that Biondi-Santi is experimenting with. Considering that some of the vines at Tenuta Greppo date back to the 1930s, it is not surprise that there would be some clonal variation, but a study by the University of Florence uncovered the presence of some 50 Sangiovese clones on the estate. 20 of these were then selected and are being studied on further, particular to see how they react to the rising temperatures caused by global warming. One downside to the research is that it has meant that the family tennis court has now been repurposed as a vine nursery.

“In the past, they used just one clone [BBS11] – in the future we plan to have a recipe of different clones that go into Biondi-Santi,” Bertolini shared.

When Bertolini joined Biondi-Santi five year ago, he also encouraged the replanting of 7ha of vineyard to facilitate the introduction of a new, specialised trellising system of movable horizontal bars with wires that support a luscious canopy: “This flexible structure allows the vines to grow like an umbrella, which protects the grapes from the sun and allows the wind to blow through and ventilate the bunches.”

The two words that repeatedly cropped up when it came to challenges in the vineyard were “climate change”, the topic that continues to dominate discussions about the long-term viability of the wine industry.

Though planting at higher, cooler altitudes can help preserve freshness (Tenuta Greppo is 560 metres above sea level), rising temperatures don’t just mean riper-flavoured wines with higher ABV, they also mean less ageing potential: “In warmer vintages, the quality compresses and the wine does not have the longevity”. This echoed what Barbara Sandrone told db recently about Barolo.

However, though warmer vintages, such as the 2017 Brunello di Montalcino (“a difficult, dry, very hot vintage,” in Bertolini’s words) may not have quite the same lifespan as cooler ones, Bertolini still estimated an impressive ageing potential of 20-25 years, as opposed to a “normal” year which might be good for closer to 50.

As for how much work goes into maintaining the vines, from pruning all the way to picking, Bertolini proudly declared: “Today, we spend more than 600 man hours per hectare per year in the vineyard. The average in Tuscany is 250 hours.”

However, Bertolini, pointing to the heavens, acknowledged that human efforts are not the decisive factor vintage to vintage: “The shareholder up there decides our lives every year!”

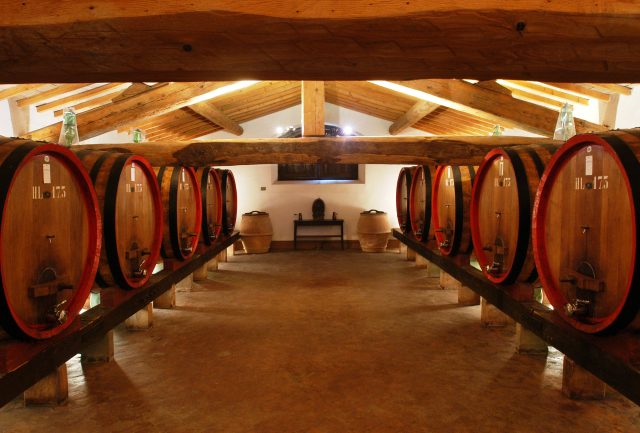

Changes have also taken place in the cellar too. Slightly smaller Slavonian oak barrels, still made by Garbellotto, are now used so that each parcel can be aged separately. Since 2021, due to the ageing advantages of larger formats, Magnums for the new Brunello di Montalcino vintages, and Magnums, Jeroboams and Methuselahs for new Riserva vintages have been produced.

“You cannot keep doing the same things you did in the past,” Bertolini stated. “You need evolution, not revolution – we have to keep this DNA.”

David Gleave MW, managing director of Biondi-Santi’s importer Liberty Wines, remarked that this philosophy was rather similar to that espoused by Tancredi in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard: “Everything must change for everything to remain the same.”