This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Does Liv-ex’s updated classification hint at a market correction?

The recently released update on Liv-ex’s classification system says much about the state of the fine wine market – and provides some hints at where it might be heading. db gets the low-down from Robbie Stevens, Liv-ex’s senior broker and territory manager for the Americas.

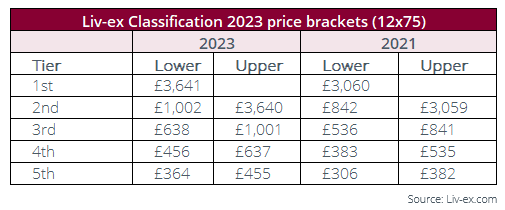

So what is the Liv-ex classification system? Broadly based on similar principles to the 1855 First Growth classification system, it was established in 2009 to determine a hierarchy of the leading labels on the secondary market, with wine spread across five tiers which are determined by price. To avoid it being unfairly skewed by one stellar trade, a minimum level of activity and number of vintages traded over the last year are required for a wine to qualify and since 2020, older vintages are preventing from influencing the average trade price by restricting it to the last ten vintages.

So what does the new classification tell us?

From bull to bear

One of the first things to notice is that the price band of each tiers has gone up by around 19%, reflecting the wider increase in prices across the fine wine market, in line with the Liv-ex 1000 – but the number of wines on it has gone down, by 53 labels.

According to Robbie Stevens, Liv-ex’s senior broker and territory manager for the Americas, this reflects the slightly unusual place that the market is currently in, straddling the period between the seven-year bull market that started in 2016, and a more bear-ish period since October 2022, when the market started to pull back.

“It means the findings are quite interesting and raise some questions,” he explains, and are different to those that would have been seen in the 2021 or 2022 classification.

“Over that period of seven years, what we saw was a broadening and the deepening of the market, with new regions coming into the spotlight,” he told db. He pointed to the 2016 vintage that catalysing interest in Barolo, the increase in demand for California wines from late 2018 through to 2022, and the broadening of the Champagne market as Grower Champagnes came to light, pushing up Grand Marques as well.

However, the last 12 months has seen a “pull-back”, categorized by a contraction in that demand, and a “flight to quality”.

“People are reverting back to the blue-chip names and veering away somewhat from those ‘new kids on the block’ angles they were perhaps exploring in the preceding years,” he explained. “And the number of qualifying wines falling down by 53 is a replication of that.”

The fact that the same five wines figure at the very top of the top tier again this year betrays the search for continuity and safety amid the current downturn, Liv-ex pointed out in the report. It is also worth noting that the 2023 Classification is “quite top-heavy”, with the top two tiers among the largest.

The market, Stevens continues, continues to decline, although the declines do seem to be getting shallower month-on-month, suggesting it may be bottoming out, although he cautions that there is no real way to conclude what is going to happen.

The market is diversifying…

Although the system launched in 2009 with only Bordeaux wines, the increase of regions being traded on the secondary market led to the broadening of the list in 2017 to include wines from across the world and that huge diversification which expanded during the height of the market has clearly left its mark and continues to be seen.

The new classification for example comprises nine countries – with wines from Spain increasing by 40.0% and Chile seeing an increase of 100%, while Argentina has not only re-entered the Classification after dropping out in 2021, but comes in with five wines, up from just one in 2019. Finally, a Swiss wine comes into the list for the first, in the second tier.

“It’s important to note these are starting from a very low base,” Stevens points out. In terms of Spain and Chile, these reflect the very top tier in each region, but potentially only an addition of one or two wines..

“They are becoming more prominent regions in the world, but are they the emerging region regions [in terms of the secondary market]? It’s probably still it’s still fair to say that the US and Champagne and the emerging regions of the of the secondary market.”

…but maybe not as fast as it was

And what of the US? The topline – that it has gone down on the list by 50%, is not great, but this should be put in the context of its meteoric rise in recent years. Savage points out for example that in 2023, there was six qualifying wines from the US in the top tier, down from ten in 2021.

“It’s not necessarily a reflection on the price of these wines having dropped,” he notes. “It’s just that the demand on the secondary market may have dropped.”

In 2021, the US accounted for around 8.5% of transactions by value on Liv-ex wines, Stevens pointed out, this year it is only 7%, so not a huge drop, particularly when it was only 2% back in 2018

“You saw this huge, huge growth, and then a slight pullback and with that pullback, people focused on specific brands,” he explains.

Other countries declining on the classification include France, down 12.9%, Italy, down 21.7%, Portugal, down by 50.0%, and Australia, which saw a 16.7% decline.

Bordeaux ‘more or less flat’

Meanwhile Bordeaux, originally the only region on the classification, only makes 29.4% of all wines in this year’s Classification, a number “more or less” flat on 2021, Liv-ex noted – although it’s perhaps worth noting that it saw something of a resurgence in the fourth tier (wines priced between £456-637 per case of 12). This is no surprise when considering the Bordeaux 500 index rose only 2.9% over the last two years, compared to the broader market benchmark, the Liv-ex Fine Wine 1000, which rose 19%, or the 36.7% growth of the Champagne 50 and34.6% growth of the Burgundy 150. “This pattern may well continue in future editions of the Classification,” the report stated.

France as a country however remained strong in the lowest tier, accounting for 61% of wines priced between £364-455 per 12, and there were new entrants from France as regions become more frequently traded on the secondary market. The Vaucluse and Loire, for example, made the list for the first time in tier 3.

but ‘there’s no cheap Burgundy out there’…

Burgundy remains in pole position at the top of the list – the most expensive wines at the top of tier 1 are all Burgundies, with Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, Romanée-Conti Grand Cru remaining the most expensive wine in the Classification, with an average trade price of £234,214 per case of 12. The region also saw a “surge” of new entrants, with 26 new Burgundies overall, notably 13 in the second highest price tier (£1,002 – £3,640), including Prieuré Roch, Ladoix Le Clou Rouge, Domaine Louis Jadot, Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru Clos Saint-Jacques and Domaine Trapet Père et Fils, Latricières-Chambertin Grand Cru made their entrance in 2023. There were also six in the top tier – although Domaine des Lambrays, Clos des Lambrays Grand Cru only narrowly missed being bumped up into the top tier.

This expansion of the number of Burgundy labels trading points to buyers seeking “relatively affordable” wines from lesser-known labels in the face of illiquidity and high prices of the most established growers – a sort of self-perpetuating speculation, Stevens notes.

Burgundy was also the most represented region in the top tier, but as Stevens notes, “With the illiquidity of Burgundy and the prices, it’s perhaps not surprising that these wines automatically categorized themselves into tiers one and two, rather than the rather than the lower tiers.”

“There’s no cheap Burgundy out there,” he says.

However, what is interesting is that the number of Burgundian wines in the Classification overall is more or less flat on 2021, implying as the report says, that “new entrants are replacing others which have fallen out due to limited trade in the past year”.

Prices, Stevens notes went up until October or November last year, but since then have been coming down “pretty aggressively”.

“Over the last 12 months, the Burgundy 150 is down 10% – but that is still up 34% over two years,” he explains.

Champagne strong at the top – for now

Champagne’s trajectory is not dissimilar to Burgundy’s in this regard. It enjoyed a strong showing are in the first tier, with ten wines, with another 12 in Tiers 2 and 3 and currently, the region accounts for 7.4% of the total Classification. Interestingly, although prices have been falling across the board since late 2022 – the Champagne 50 is down 10.4% year-to-date and 8.3% year-on-year – the average trade price for Champagne wines in the 2023 Classification remains a lot higher now than it was in 2021, the report stated. This implies “the effects of this correction have either not yet been reflected in the data, or that sustained demand and relatively consistent trade are buoying the region’s performance”.

A corrective phase

Stevens argues that following a “mixed” en primeur season, and now a beyond Bordeaux campaign “that has largely failed to garner the interest of the majority of wine buyers”, merchants in the UK and Europe have begun to open up to the reality that prices have moved and in order to do business and sell wine, they need to adjust their prices.

“That adjustment has been happening over the last three, four or five months and I think it’s continuing to happen,” he said. “At the moment we’re starting to see bids return, but at levels 10-15% below the market.”

These “opportunistic buyers” are creating a bit of a floor that is “propping up the downturn”, he says, even though “we are continuing to see declines”.

“The market is in a corrective phase. It’s anyone’s guess as to how long that corrective phase lasts, but we can use data and previous performance to just to judge what might happen,” he concluded.