This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Bordeaux 2022 by appellation: Saint-Émilion, ‘excellent value at every price point’

My first appellation profile was of Pomerol where, I suggested, the 2022 vintage came close to outright heterogeneity, with spectacular highs but also some rather more problematic wines. That might lead one to expect something similar in Saint-Émilion. For, traditionally, we think of Saint-Émilion as heterogenous even in the greatest of vintages and to a degree that Pomerol is probably not.

But it is not true in 2022. One can never buy Saint-Émilion with one’s eyes closed, above all en primeur, and I am not suggesting that now is the time to start. But this is, in the end, a Saint-Émilion vintage where the probability of finding excellent value at any price point is high – perhaps more so than in any other of the leading appellations.

And that takes just a little bit of explaining.

We think of Saint-Émilion as having an almost natural tendency to heterogeneity for three reasons above all: first, its sheer size; second, the qualitative range and diversity of its terroirs and, crucially, their respective capacities to respond to the climatic conditions they face; and, third, its stylistic diversity.

All three factors are of course present in 2022. So what’s going on here?

Let’s start with the obvious. The size of the appellation has not changed (or not, at least, in any way relevant here) and neither has the differential capacity of its various terroirs to endure the meteorological conditions of the vintage.

But that brings us directly to a first significant point. For the meteorological conditions were not the same in Saint-Émilion and Pomerol. Here, as ever, a little detail helps.

|

Pre-budburst (Nov-March) |

Véraison to harvest (August-October) |

Total | |

| Margaux | 381 (-22.8%) | 58.5 (-53.0%) | 802 (-12.3%) |

| St Julien | 364 (-25.0%) | 61.3 (-47.7%) | 780 (-12.2%) |

| Pauillac | 364 (-25.0%) | 61.3 (-47.7%) | 780 (-12.2%) |

| St Estèphe | 415 (-14.6%) | 74.4 (-40.3%) | 889 (-1.1%) |

| Pessac-Léognan | 445 (-8.4%) | 57.7 (-50.7%) | 764 (-14.6%) |

| Saint-Émilion | 558 (+14.8%) | 67.7 (-44.0%) | 886 (-1.9%) |

| Pomerol | 541 (+9.7%) | 51.2 (-57.5%) | 871 (-3.9%) |

Table 1: Rainfall during the vintage (mm, relative to 10-year average)

Source: calculated from Saturnalia’s Bordeaux 2022 Harvest report

As Table 1 shows very clearly, and like Pomerol, Saint-Émilion saw more rainfall during the winter months than in left-bank peers, with an average of 558 millimetres in the months from November 2021 until March 2022. Significantly, that was both above the 10-year average and the highest of the leading appellations. It served to recharge and replenish the water table. When vines searcher for water later in the year those with well-established root systems found it. That was a crucial factor in both Saint-Émilion and Pomerol, but more decisively so in the case of Saint-Émilion.

But what the table also shows is that the drought conditions during the ripening period (between véraison and the harvest itself) were less intense on average in Saint-Émilion than they were in any of the leading appellations other than St Estèphe (when gauged in terms of total rainfall). Indeed, here it was Pomerol that suffered the most (with the lowest total rainfall over the period even when expressed as a percentage of the 10-year average).

In short, whilst winter rainfall credibly saved the vintage in Pomerol it merely helped Saint-Émilion endure it more successfully. That might sound like a passing detail – a subtle difference in emphasis – but it turns out to be highly significant in the glass.

Yet we need to be careful here. For there are two caveats that immediately need to be mentioned. The first is that appellation level averages can be misleading, especially for an appellation the size of Saint-Émilion and especially in a vintage like this.

Whilst Saint-Émilion certainly had more rain, it turns out that much of it fell on the parts of the appellation that needed is less (where, in short, there was little hydric stress). And, consequently, there were other parts of appellation – and not just those bordering Pomerol – that experienced meteorological conditions no less extreme than those across the appellation border. But, frankly, not many of the leading wines of the appellation come from the expanse of less contoured vineyards on those (‘well-draining’) sandy soils bordering the river. I would think twice before purchasing such wines en primeur, certainly without having tasted them first.

The second caveat is that, even had the meteorological conditions been the same, they would have impacted the diverse terroir types that together comprise the appellation very differently. Whilst some parts of the appellation suffered intense hydric stress under ostensibly similar drought conditions others did not.

As this suggests, the leading wines of the appellation – the (current and former) Saint-Émilion grands crus classés – tended to fare well in 2022 for three reasons. First, the meteorological challenges that they faced tended to be less intense that those endured by their peers in the other leading appellations. Second, the meteorological conditions that they faced were typically also less severe than those endured by their neighbours on lesser terroirs within the appellation. And, third, and rather more positively, many of these wines hail from terroirs that are almost perfectly well adapted to cope with the challenges of a vintage like this. This was above all the case for those on clay and limestone or pure limestone on the côtes and plateau. For such wines, and strange though it might seem, this is an almost perfect vintage meteorologically.

A further factor is also important here. Saint-Émilion is very much at the vanguard of changes in vineyard management that have helped vineyards to adapt to and cope with hydric stress in a context of accelerating climate change. This is partly a consequence of clear and conscious choice. But it is also, and perhaps just as much, the serendipitous consequence of habit. On heavy clay soils, as explained to us above all at Angélus, Saint-Émilion producers have always use of vegetal cover. For, without it, the tractors simply cannot get through the vineyard when it’s wet!

The effect of all of this is very clearly demonstrated in Table 2. It compares the average vineyard yields of the Saint-Émilion grands crus to those achieved in the other leading appellations.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 10-year average | Relative to 10-year average (% change) | |

| Margaux | 37.4 | 49.2 | 36.3 | 38.6 | 31.3 | 39.7 | -21.2 |

| St Julien | 42.6 | 45.5 | 34.3 | 35.2 | 34.3 | 40.1 | -14.5 |

| Pauillac | 38.5 | 46.7 | 37.4 | 35.1 | 34.8 | 39.7 | -12.3 |

| St Estèphe | 44.6 | 49.7 | 41.2 | 40.7 | 31.5 | 43.4 | -27.4 |

| Pessac-Léognan | 36.9 | 47.2 | 34.6 | 30.7 | 35.7 | 38.5 | -7.3 |

| Saint-Émilion (GC) | 39.7 | 43.0 | 36.7 | 27.5 | 41.2 | 37.2 | +10.7 |

| Pomerol | 36.2 | 43.0 | 39.8 | 28.9 | 32.3 | 36.1 | -10.5 |

Table 2: Average vineyard yield by appellation (hl/ha)

Source: calculated from Customs data compiled by the CIVB Service Economie et Etudes

What it shows is that, amongst the leading appellations, Saint-Émilion attained not only the highest average yields, but also that it was the only appellation where yields exceeded the 10-year average (coming quite close to those attained in 2019 and significantly exceeding those in 2020 and, of course, 2021).

When it is considered that vineyard yields were often highest for the grands crus on the very best terroirs and, unusually, from the oldest vines, one begins to understand why many of the best wines of the vintage come from here.

There is a third factor that also helps to explain the perhaps surprising homogeneity of at least the leading wines of the appellation in this vintage. It is a factor that I mentioned too in both 2020 and 2021. It is a certain convergence in stylistic conventions between the leading crus.

There’s a lot more that could be said on this. But perhaps the simplest way to put it is to suggest that, like the appellation of Margaux on the left-bank, Saint-Émilion was the most influenced on the right-bank by Parker – or, more accurately, by the style of wine-making with which he came to be associated. The result was a stylistic divergence between the traditionalists, on the one hand, and the modernists (and their fifty shades of Parkerism), on the other.

It is perhaps not then surprising that, like Margaux again, Saint-Émilion has been most marked by the retreat from ‘peak Parker’. That trend continues and it is very clearly evidenced in the leading wines of the appellation in this vintage. They are wines that I have elsewhere referred to as expressive of a certain ‘new classicism’ .

The wines themselves

What is interesting, after all that analysis, is that other than the overall quality and evenness of the leading wines there are relatively few surprises when it comes to individual wines themselves.

What is interesting, after all that analysis, is that other than the overall quality and evenness of the leading wines there are relatively few surprises when it comes to individual wines themselves.

As ever, though, there are little pockets or clusters of excellence linked to the sheer quality and distinct personality of a particular terroir type (further illuminated by the ‘new classicism’ itself). Let me signal perhaps four.

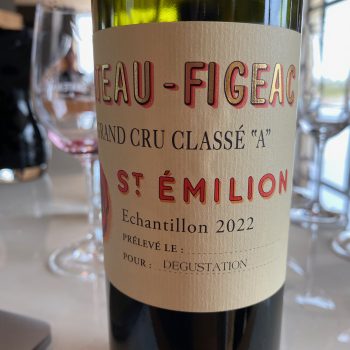

The first is, of course, along the border with Pomerol. Here, unremarkably, both Cheval Blanc and Figeac shine resplendently. These are two of the very greatest wines of the entire vintage.

The second is the strip of limestone pleateau and côtes that starts at Beau-Séjour Bécot and continues past Beauséjour Duffau-Lagarrosse, Clos St Martin, Berliquet, Canon and Bélair-Monange before descending to Calicem, Le Dôme and Angélus (now with the inclusion of some Merlot parcels from Bellevue). Each of these wines has its own personality (and although there are similarities, their terroirs are far from identical), but each supremely expresses the supreme quality of this exceptional terroir ‘hot spot’.

A third hot spot is something of an insiders’ secret. If there is one part of the appellation, these days, where one is almost guaranteed to leave a tasting with a smile it is here. It is to be found on almost the highest part of the appellation, again on the limestone plateau and côtes, this time around Saint-Christophe-des-Bardes. Here we discover, for me, some of the rising stars of the appellation – most notably perhaps, the trio of David Suire’s Laroque, Peter Sisseck’s Rocheyron and Axelle and Pierre Courdurié’s Croix de Labrie. Each exceeds it previous high for me in this vintage.

And, finally, I would signal the Côte de Pavie itself. This is both a literal and a figurative hot-spot (given its famous southern exposure), but it has produced fabulous wines once again. It runs from Pavie via Larcis Ducasse and on to Bellefont-Belcier (a particular triumph in this vintage) and a little further on to Tertre Roteboeuf.

There are other stars too. As ever there is the brilliant trio of Troplong Mondot, La Mondotte and L’If (the finest vintage of this wine yet produced), each fabulous in the context of the vintage. And I would also single out an utterly sublime Ausone, its close sibling La Clotte and, a little further down the slope, La Gafferière.

Let me finish with what I think is a fascinating observation that only struck me as I typed. I have listed 24 stars of the 2022 vintage in the preceding paragraphs. Of those 24, 12 feature in the new classification of the wines of Saint-Émilion that will come into effect with this vintage, but 12 do not. There is a lot to be written on the implications of that. But, for now at least, let me just leave the thought hanging in the air.

Highlights in 2022

Best of the appellation:

- Ausone (98-100)

- Beauséjour Duffau-Lagarrosse (98-100)

- Cheval Blanc (98-100)

- Figeac (98-100)

Truly great:

- Angélus (97-99)

- L’If (97-99)

- Rocheyron (97-99)

- Clos Fourtet (96-98+)

- Bélair-Monange (96-98)

- Canon (96-96)

- Clos St Martin (96-98)

- La Clotte (96-98)

- Croix de Labrie (96-98)

- Laroque (96-98)

- Pavie (96-98)

- Tertre Rôteboeuf (96-98)

- Trottevieille (96-98)

- Troplong Mondot (96-98)

Value picks:

- Beau-Séjour Bécot (95-97+)

- Bellefont Belcier (95-97+)

- Berliquet (95-97+)

- Calicem (94-96)

- Grand-Corbin Despagne (94-96)

- Dassault (93-95+)

- Fonplégade (93-95+)

- Couvent des Jacobins (93-95)

- Fonroque (93-95)

- Haut Simard (93-95)

- Quinault L’Enclos (93-95)

- Chauvin (92-94+)

- Fleur de Lisse (92-94+)

- Puyblanquet (92-94+)

- Peymouton (92-94)

For full tasting notes, click here.

Please click link for db’s 2022 en primeur vintage report, along with appellation-by-appellation reviews (links updated as they become available) on Margaux, St Julien, Pessac-Leognan & Graves rouge and blanc, St Estephe & Haut-Medoc, Pauillac, Pomerol, Saint-Émilion and Sauternes.