This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Study of 200,000 wine scores shows organic wines ‘taste better’

Wines produced from organic or biodynamically produced grapes do taste better, according to two separate studies analysing the scores of 200,000 wines given by independent critics in both California and France.

Magali Delmas, a professor at the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, and Olivier Gergaud, a professor of Economics at the KEDGE Business School in Bordeaux, first published a study in 2016 analysing the scores of wines produced from organically grapes in California.

The pair looked at the scores of 74,000 wines rated by Robert Parker, Wine Enthusiast and Wine Spectator, finding that critics scored eco-labeled, organic California wines 4.1% higher than conventional wines – those not certified by a third-party organisation as organic or biodynamic.

In February 2021, the pair published the results of a second study in the journal Ecological Economics, this time looking at 128,000 wines produced in France, and again found that those certified organic, or biodynamic, scored higher.

In this study, scores were collated and analysed from Gault Millau, Gilbert Gaillard and Bettane Desseauve, which scored the third-party-certified wines an average of 6.2% higher than those that were self-labelled organic. Wines that were certified as biodynamic by the third-party association performed even better, scoring 11.8% higher.

Wines that were self-labelled as having been produced using conscientious practices, according to the Lutte Raisonée standard for example (where winemakers are reasonable in their approach to sustainable wine growing practices but not beholden to it) received scores that “weren’t measurably different” from those of conventional wines, adding weight to the value of being held accountable to formalised accreditation processes, be it organic or biodynamic.

Why do winemakers hide their organic certifications?

Speaking to the drinks business, Delmas explained the motivation behind the research, which was rooted in the fact that while many winemakers invest heavily in organic and sustainable winemaking practices, they don’t necessarily publicise their methods or organic certifications on their bottles.

“Jim Fetzer [of the Fetzer family and Ceago Vinegarden in California] explained that while he was into sustainable and organic winemaking, he didn’t want to use the organic label because it had such a bad rep, so he was going to use this new thing called biodynamic,” said Delmas. “Which was a view in contrast to organic produce like tomatoes or strawberries – people tend to think it’s better for health and the planet – but with wine there was this negative perception among consumers.”

Delmas and Gergaud also surveyed Californian winemakers as part of the 2016 study, finding that one third of the wineries that had adopted organic certifications, which is 15-20% more expensive to manage, hadn’t put it on their label.

“To me this was a strange thing. Why would you go through this painful process and get certification and then not talk about it to consumers? Any other industry if you invest in something you want to talk about it.”

For winemakers, the primary benefit of sustainable wine growing has been in safeguarding their land for future generations, rather than for marketing purposes.

What Delmas’ and Gergaud’s study has found is that there is also a marked increase in the quality of wines produced using organic or biodynamically farmed grapes based on their assessment by wine critics, which while recognised among winemakers, has not necessarily been communicated effectively to consumers.

In some cases, winemakers have chosen to omit accreditation from their labelling entirely in favour of being considered “more mainstream” by consumers, says Delmas.

This misplaced stigma needs to be addressed, believes Delmas, with this study highlighting the disparity between the perceptions of consumers, experts and winemakers.

‘If there is any trade off between the quality of the product and the environment, then the environment loses’

Part of the problem with consumer perception, she says, has been that in the early days of the organic and natural wine movement quality was more patchy, with winemakers perhaps less skilled in wine growing without chemicals and a lot done by “trial and error”.

“It’s a little bit different natural wines where you have no sulphites,” says Delmas. “But if you add a little bit of sulphite and use grapes that are grown organically there are reasons to believe this will lead to improved quality, because you are replacing chemicals with labour. So if you have an experienced winemaker it should lead to higher quality.”

Another challenge has been in drawing a connection between organic wine and better health, as is possible with organic produce such as strawberries or potatoes. Generally consumers are not willing to sacrifice anything for the public good unless they are getting a private benefit as well, says Delmas, and that connection to health is harder to make with wine.

“With wine, if there is any trade off between the quality of the product and the environment, then the environment loses”, she says. “People are willing to pay a little more but they want the quality to be the same. You can offer high quality and health benefits with organic wine, but it needs some explaining.”

Perceptions are changing, she says, with a younger generation more open to organic wines, spurred on perhaps by incidents such as the one she cites in Bordeaux in 2014 where a school had to be evacuated and children treated in hospital after pesticides were sprayed nearby, leading to protests and pressure on the French wine industry to evolve its practices more rapidly.

“I think people have this very bucolic view of winegrowing”, adds Delmas. “You don’t think about the pollution but a winery that’s green with a beautiful landscape. Consumers don’t necessarily think about the impact of pesticides and water on the health of people. The main driver will be that winemakers think [organic and biodynamic] is better for their health and the environment, and then we need to get consumers to think of sustainable practices as valuable and avoid this stigma by helping winemakers to achieve better quality wines.”

Global organic wine market forecasted to grow 43% by 2024

Uptake in organic farming is also on the rise, albeit still representing a small percentage of production. Of the 128,000 French wines analysed in Delmas’ and Gergaud’s second study, just 3.87% of wines were third-party certified as organic or biodynamic from 1995 to 2000. However this figure increased to 7.37% for wines produced between 2001 and 2015, indicating an increase in accreditation and commitment to the movement.

Overall, the global organic wine market was forecasted last year to grow 43% by 2024, while larger companies too are increasingly committing to organic practices, which Delmas says is needed in order to “legitimise” organic winemaking in the minds of consumers at large.

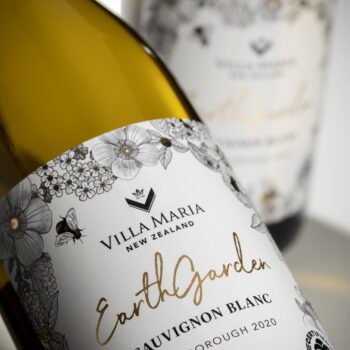

This month New Zealand’s Villa Maria announced the launch of its first organic wine range, certified by BioGro. The ‘EarthGarden’ organic wine range will include a Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc 2020, Hawke’s Bay Rosé 2020, Marlborough Pinot Noir 2019 and Hawke’s Bay Merlot Cabernet Sauvignon 2019, and are part of Villa Maria’s commitment to converting 100% of its vineyards to be organically managed by 2030.

Villa Maria viticulturalist Hannah Ternent said: “Organic farming accentuates flavour in other natural produce such as fruits and vegetables, and it’s the same for wine too. Wines made from organically grown grapes have more intense and evocative flavours. When you taste the EarthGarden wines, you taste the care put into the soil, the conscious tending of the vines, the careful handling of the fruit produced and the respect for our relationship with the land.”

With regards to biodynamic certifications, Delmas acknowledges that it is perhaps more upscale wineries with the margins available to work in this way that are choosing to commit to these practices, but that in doing so produce higher quality wines than conventional methods.

“If I take Jim Fetzer, clearly he was working within the £30+ price range for his bottles and having the margins available to do this so it was going to be a high quality wine. Those that are a little more upscale might choose biodynamic depending on the amount of resources they have to devote to the process.

“What we find is that biodynamic tends to lead to higher quality wines, but it’s a more complex set of practices for your investment. The first phase is organic. The second phase is biodynamic.”