This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Why ‘regenerative viticulture’ is gaining ground among major wine producers

Moët Hennessy, Jackson Family Wines and Torres are adopting a ‘regenerative’ approach to viticulture – but what does it involve, and why are these famous producers making the move.

As reported by db a couple of years ago, the main aim of regenerative viticulture is to increase the amount of carbon held in the ground, and to do this, farmers must ditch the tilling, because the best way to destroy carbon in the soil is to turn it.

In short, disturbing the ground exposes it to UV light, which is an oxidising force, and breaks down the organic matter in the soil.

And a soil with less organic matter is less sponge-like, and less able to absorb and hold water and nutrients – as written about on thedrinksbusiness.com earlier this week. Tilling the soil also disrupts the soil microbiome, killing the good microbes and insects that help fight pests and diseases.

However, vineyard managers plough, because the pervading farming philosophy suggests that you need to turn soil to aerate it, as well as to get rid of any crop-competing weeds.

For Justin Howard-Sneyd MW, who heads up courses on Sustainable and Regenerative Viticulture at the UK’s Dartington Trust, a regenerative approach is vital to reverse the damage done to agricultural soils, and make viticulture sustainable, without detrimental effects on grape quality.

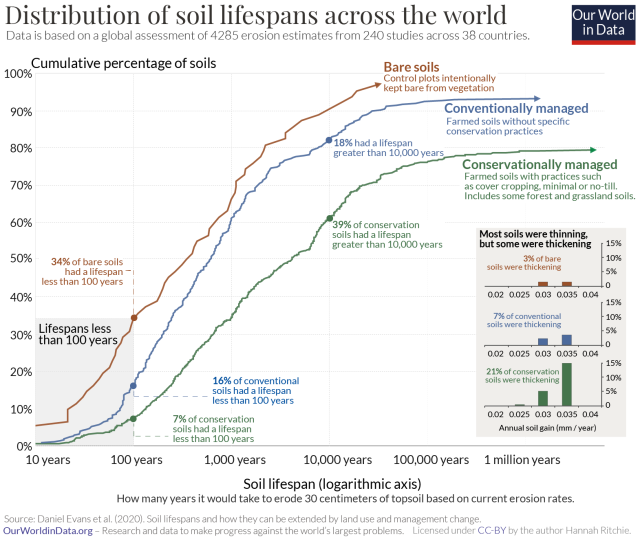

Speaking last month at the IMW Symposium in Wiesbaden, he told more than 500 attendees at the three-day event that the world has “a significant soil degradation problem,” before commenting that “we have just 60 harvests left”, should current rates of soil erosion continue*.

Indeed, he recorded that the origins of the regenerative movement was the Dust Bowl of the 1930s in the US, where deep ploughing and drought saw the destruction of virgin topsoil in the Great Plains of central North America, forcing tens of thousands to abandon the land.

“Fast forward 80 years,” he said, and the lesson is “never leave the ground bare”, noting that the Dust Bowl “kicked off the understanding that if you take everything from the soil, it will blow away”.

For Justin, a regenerative approach to viticulture carries additional advantages of being applicable to any farming philosophy, with no strict practices, while being “science-led”.

“It is about trying as much as possible to create a complex, balanced, diverse ecosystem of life in the vineyard by working with natural forces,” he said.

This is in sharp contrast to conventional viticulture, stressed Justin, which sees farmers “find a problem and kill it, which causes another problem – it unbalances the system.”

Furthermore, even certified organic vineyards can create issues for soil health, with Justin recording that “If you are organic, but plough a lot and use a lot of copper, then you can actually have fairly unhealthy soil.”

To promote the techniques and benefits of regenerative approaches to wine production, a little over 18 months ago the Regenerative Viticulture Foundation was established, and Justin is a trustee, along with several others, including wine producers Stephen Cronk of Maison Mirabeau in Provence and Mimi Casteel of Bethel Heights in Oregon.

Commenting on the organisation’s establishment, he urged producers to turn to the foundation to better understand the approaches and find out from others who already employ regenerative techniques in a range of climates.

Notably, Justin recorded how some large-scale and famous wine producers are now moving towards regenerative approaches, proving that it can be practised on a large scale.

By way of example, he mentioned at the symposium that Jackson Family Wines had committed to converting all its vineyards to regenerative techniques by 2030, while Torres was moving towards the approach on more than 500 hectares of organic vineyards, and Moët Hennessy was also adopting the philosophy, most notably at its Provençal property, Château Galoupet, although it is also trialling it in Champagne, while the group’s Argentine estate, Terrazas de los Andes has been awarded Regenerative Organic Certified status, along with Chandon Argentina.

Meanwhile, Concha y Toro is experimenting with regenerative approaches in Chile – its US estate, Bonterra already a long-time advocate – while the Guilisasti family, who are majority owners of the group, farm their Viña Emiliana regeneratively.

What’s drawing these major names in the wine business to regenerative approaches? Justin hopes it’s a desire that “growing grapes will positively help the planet”, but it’s also because the approach can improve soil health, reduce the need for increasingly expensive inputs, be they organic or synthetic fertilisers, as well as create a vineyard that is more resistant to weather extremes – particularly periods of heat and drought.

Indeed, should the vine be healthier as a result of regenerative viticulture, it will be longer lived, as well as the source of more regular yields.

Also present at the symposium was the aforementioned Mimi Casteel, who said that permanent ground cover in her vineyards had kept her soils wetter and therefore cooler during a recent period of extreme heat in Oregon.

“We are keeping water in the soil by not tilling,” she said, adding, “But most people think that you must till during a heatwave to get water to the vine.”

She showed a picture of a temperature measuring device for her vineyard soils compared to her neighbours during this episode, which proved that Casteel’s Bethel Heights soils were 60 degrees cooler than those at the estate next door, who, she recorded, “had ploughed just before the heatwave.”

The issue of soil water levels in regenerative viticulture was a topic that db has previously discussed with Jean-Marc Lafage and Antoine Lespès at Domaine Lafage in Roussillon.

For this estate, where average annual rainfall is below 500mm – and the majority of vineyards are farmed without irrigation – building a better water holding capacity is vital. As Antoine Lespès – who heads up R&D at the domaine – told db in December last year, “Because we have a low amount of rainfall, every drop that falls from the sky needs to be cultivated.”

To ensure this, Lespès said that a permanent ground cover was key for increased infiltration, and a high-level of organic matter was important to retain the moisture. He also said that the ground cover, which can be rolled or mulched, prevents water loss by shading and protecting the soil.

Other techniques are necessary too, however, from planting to follow the contours on sloping ground to prevent run-off during heavy rainfall, to the use of agroforestry for shade, along with biochar for increased water infiltration and retention, and, finally, a good combination of rootstock and grape variety.

Jean-Marc Lafage recorded, “We’ve had a few very dry years, and 2022 was one of the driest we’ve ever had, with 5-7 heatwaves, and, at the end of the year, we saw that R-110 with Grenache and Carignan were the two best combinations in that extreme.”

In other words, regenerative viticulture can be applied in very dry climates, but vineyard layout, rootstock and variety need to be considered too.

But it was also an emphasis on applying regenerative viticulture to large-scale production that was stressed at the IMW Symposium, and particularly by Jamie Goode, who, as the author of Regenerative Viticulture, also spoke on the farming philosophy.

Commenting on the fact that regenerative viticulture can be applied to create “appropriate yields for quality wine making”, he stressed that the approach was “not just for boutique level producers with 3-4 hectares.”

Continuing, he said, “We want it to be applied to large vineyards in areas such as Australia’s Riverland or the Central Valley of California, where things need to change.”

He added, “If this approach to farming is going to make big impact, then it’s not just something we want rich people to do on a small vineyard for wines selling for $100 a bottle – it’s also for big farms selling wine at €1 per litre.”

It was also notable, bearing in mind the debate regarding weedkiller use in viticulture, that Jamie said it was important that wine producers “say goodbye to herbicides.”

Explaining the remark, he said the problem with their use was the fact they leave the soil bare. “Nothing is growing there – that is problem; the fact there is clear earth is a major problem, not so much the chemicals. It’s the same problem with organic herbicides: nothing is growing there.”

However, should one leave a permanent ground cover, and ditch the tilling, the plants that sprout in the vineyard do need to be kept in check. Having noted that there “are lots of weed-control devices around now to deal with the problematic area in a vineyard that is the area directly under the vines”, Jamie also said that some growers were using animals.

Calling the solution “complicated”, he mentioned “chickens” as a way of keeping the weeds down, although he said “you have got to keep them safe from predators”. Sheep are also used, but he warned that “they can get on their haunches and eat the grapes”, and suggested bringing them into the vineyard during the winter, or changing the training regime to make the fruiting wires higher.

Nevertheless, California’s Tablas Creek, which is a pioneer in regenerative viticulture, has a herd of 250 sheep that it successfully uses to keep weeds at bay in its vineyards (and click here to read more about this producer’s approach).

Among other animals used are geese, which are employed at Vina Emiliana, and move around in moveable sheds before being released where necessary, as well as runner ducks, which eat grasses as well as bugs at Vergenoegd Wine Estate in Stellenbosch.

Finally, Goode mentioned Luis Pato in Portugal’s Bairrada region, which is using pigs to keep the ground cover low, and noted more generally that, despite the challenges, animals in the vineyard do an excellent job at nutrient recycling.

Read more

How no-till farming could provide the key to combatting extreme weather

How a few changes to vineyard management could help save the planet

Meanwhile, presenting the case for more conventional farming systems, read this comment piece by Stephen Skelton MW, entitled, How to control weeds in a viable vineyard enterprise