This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Beer found in 9,000-year-old Chinese pots reveals ancient burial ritual

Archaeologists in south-east China have found microfossil residues left over from early beer drinking at a large burial site. The discovery is thought to evidence ancient drinking rituals at funerals.

Ceramic vessels unearthed in what is thought to be an ancient Chinese burial site have been found to contain starches, plant residue, and fungal remains, indicating that they once held alcohol.

The findings, reported in the PLOS One journal last month have led researchers to conclude that beer was used in ancient burial rituals in southern China, in order to honour the dead.

The cache, found alongside two human skeletons on a burial mound almost the size of a football pitch, represents the first evidence of beer drinking in the context of burial rituals in southern China.

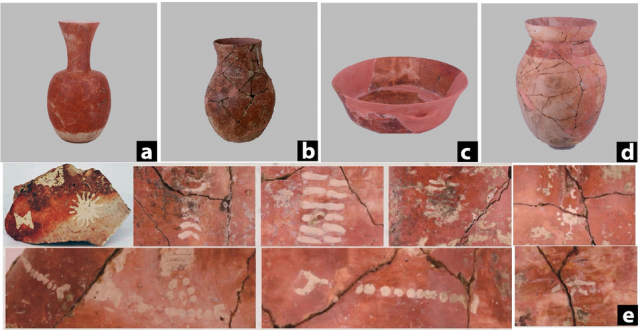

Analysis shows that the four bowls, nine jars, and seven long-necked hu pots, thought to be around 9,000 years old, once housed a rice beer made using a mould starter.

“This ancient beer would not have been like the IPA that we have today. Instead, it was likely a slightly fermented and sweet beverage, which was probably cloudy in colour,” said archaeologist Jiajing Wang, lead author of the study, in a press release.

“If people had some leftover rice and the grains became mouldy, they may have noticed that the grains became sweeter and alcoholic with age,” said Wang. “While people may not have known the biochemistry associated with grains that became mouldy, they probably observed the fermentation process and leveraged it through trial and error.”

Perhaps most notable is the fact that rice farming 9,000 years ago was only in its very early stages in this part of China, suggesting that the process of fermenting rice for alcoholic beverages would have been something reserved for special or important occasions, such as marking the passing of respected figures within the community.